Radical Lives in Contemporary Europe: Ghédalia Tazartès and Jim Haynes

Paris, that phantom, corrosive state of mind America dreams of, sometimes in bright lights, sometimes adrift in a lake of splendid isolation, is celebrating the 150th anniversary of its great communal uprising. A town that nurtures rebels, it’s in the water, the filthy, whispering Seine, down after its winter rise, assaulting the walls meant to hem it in and the air that, over the centuries, scours the faces of the great men on the buildings. The city reels disaster to disaster, terrorist attacks to bloody tussles with the cops, with Parisians sensing, quite rightly, that some new outbreak is just over the horizon. Not the Apocalypse, though, never the end of things. Paris has been around too long, escaped and embraced too many tragedies, to ever say this is it. I remember Avenue Montaigne in November ’18, during one of the first and most violent clashes between the Gilets Jaunes and the cops, standing there getting soaked in the encroaching dark, while a player sat on a heap of piled up barricades and picked his way through a tune, as carefree as a summer day. The rain was ricocheting off the metal, the sirens blaring, cop cars tearing past the chi-chi boutiques in what was now a war zone – it felt like time had come to a brutal pause, and there we were, stranded on a ruined stage in a moment of eternity. Maybe the guitar player was the last man – or the first.

Paris lost two of its sacrés earlier this year. Jim Haynes, born 1933, Ghédalia Tazartès class of ’47, ripe ages for savants in the arts game with all its built-in anxiety. One born in the eleventh arrondissement which he only left on rare occasions, and the other, Parisian by adoption, who took a circuitous route from Haynesville, Louisiana to rue de la Tombe d’Issoire in the 14th. Both men made their dent on the world and yet neither leaves behind a well-loved masterpiece, a stand-alone piece of art. They won’t be remembered for that.

Social media and instant communications supposedly bring us closer and, sure, the universities turn out their cultured, opinionated graduates but do readers know who Tazartès or Haynes were? Men and women who operate below the radar are even further away now. How would an American get here to soak it up anyway, who can even think about doing it in plague time, living precariously in an America on the cusp of civil war, everyone behind masks and aiming for each other’s throats?

Tazartès is the more difficult of the two men to place, and not just for Americans. The obituary in Libération suggested that apart from avant-garde circles, he was virtually unknown in Paris. Likely so, despite touring Europe in the later years of his life. Tazartès grew up hearing Ladino in a Judeo-Spanish family, one of half a million refugees who traipsed into France in the years after Franco seized power. A revered figure in the underground, Tazartès seems to have lived his whole life as a playful, dignified child. Without being a musician in the sense of formal training, he invented a territory where he could exist and sing.

When my grandmother died, I went to the woods and began to sing. I was singing for myself, for God. I hadn’t been very kind to her, and she was a saint, while I, as a young boy, was a little devil. When she died, I realized I had no more chances to be kind to her. That inner turmoil pushed me to sing.

A trip to the South of France in his youth led to an encounter with « some kind of beatnik, » who brought poetry home to him. He read voraciously, joined rock groups for a gig or two, worked with choreographers and created the music for a successful run of Godot, all the time unsure where he was headed. In 1979 Diasporas came out on a small label. It’s a feat to make a first record which so entirely resists being absorbed into the mainstream that forty years later it still sounds raw and strange and even unbearable, filled with the mad jumble of Tazartès noisy, homemade, multi-layered tapes. Halfway through you’re about to run out of the room when Tazartès glides into a tango with lyrics by Mallarmé. It’s a great record to listen to at high volume in a cold studio early in the morning but make sure your significant other has gone out for bread or cigarettes.

For me, I wasn’t doing music at all. I was doing something with sound, painting maybe. You close your eyes and see abstractions, colors, maybe images, your own images. My idea was to do some immaterial art, not music in particular. I wasn’t thinking, I am a musician, because I didn’t play any instrument and never studied. It was pretentious to claim that.

It’s hard to describe Tazartès in concert. It’s very awkward until suddenly it’s overwhelming. A self-effacing man in a fedora stands in front of you, alone. He looks out of place, not exactly lost but as if he too were waiting for something to happen, his dark eyes surveying the audience when not staring at the floor. You feel like you’re in a train station, killing time. The night I saw him in Boulogne-Billancourt, he started with two harmonicas piled on top of each other, very ad hoc, which he then put down in favor of a vibrating metal bowl, chanting softly in an unknown language. A touch ridiculous. And then it slowly begins to build into a something I now realize is called Alleluia. Not the Cohen song, but a voice howling and growling through a maze of menacing, multi-leveled sounds. I didn’t know what to make of it. Tazartès wasn’t a musician or a maestro, that was obvious. Dada? Throw in all the references you like. By the end of the performance, Tavares was covered in sweat, and the crowd was in a kind of rapture. They’d completely forgotten they had a train to catch. His music is mystery, a ceremony in the dark. It’s his voice, warm and yet distant, urgent, speaking in tongues – a ritual we’ve walked in to without any preparation, a sound from somewhere far away, expressive and operatic in an invented language. A little like a cantor but traditional and radical at the same time, belonging to no one.

Oh, it’s really just my own language. There is no sense to the words, only their sounds. I don’t like singing in French—though I do it rarely, always with humor, like a joke. And in English, with my dirty accent? No way. But there’s also something more to it—my parents would often talk together in Ladino, and so we children were unable to understand what they were saying. Thus, if they could have their own language, I could have mine too. So I invented words. … If you sing in the opera, you have to work a great deal to get the voice coming through, and you have to learn many things. But I’m born with mine. It’s only chance, or something given to me. Either way, I haven’t been grateful enough.

Sometime in the early Seventies Tazartès had the temerity to take the stage at Café OTO, at that time a center of Parisian musical life. Backed by his homemade tapes, Tazartès closed his eyes and headed off into a trance, only to find himself face to face with an enraged François Bayle. An epic confrontation: Bayle, twelve years older, the head of Groupe de Recherches Musicales, a composer in the musique concrète style, who by his early thirties had already won Europe’s prestigious music prizes. Perhaps afraid that an inspired amateur was making off with his magic, Bayle took an instant dislike to the young nobody. He insulted the audience for giving the man the time of day. ‘How can you listen to this shit?’ Tazartès remembers him hectoring the crowd. One cannot imagine two men with more opposite agendas. One on the prosperous route of official funding, composing in an acceptable, if difficult, style, the other inventing a world out of his hat, making something with no name. Yet to attend one of his performances was to see someone transform – through the medium of his body and his voice – into a kind of – what? « Not a sorcerer, not a poet, not a sound painter, not a shaman, » he replied. « I’m flattered. A biologist of sound maybe. The resonance of the world is sufficiently rich… » Tazartès travelled Europe but in a sense never left his apartment. His shouted-sung versions of Rimbaud –what a contrast ! An older man, content all his life to babel in tongues, reading the heady, pointed poems of a teenager – are bull’s eyes, nothing aesthetic or Academie Française about them. You could start with those, or his soundtrack for the 1922 silent Häxan.

What used to be called Radical Lives may still be in abundance in secret corners of the world, so secret that even Paris doesn’t know their neighbors are cooking it up. It’s not the precious announcement on social media that counts but what you do with your freedom. Tazartès had to make money for his family but he kept the project going amiably, making sounds that weren’t considered music by most people and many other musicians.

Apart from Paris, where, as far as I can tell, they never crossed paths, maybe what links Tazartès and Jim Haynes are the bulky old Revox reel-to-reel tape decks they owned at the same time. Tazartès used one in the early Seventies in his quest to produce multi-layered ambient noise and voice, while Mick Jagger gifted one to Haynes so he could produce the audio magazine, The Cassette Gazette, whose first issue featured Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Charles Bukowski. In the seemingly unending stream of Haynes’ contacts, that led to passing interest from John and Yoko, as well as City Lights becoming one of Bukowski’s first publishers, back when he was unknown. But I digress…

If you had met Jim Haynes as I did, at one of his famous Sunday dinners in the alley off Tombe d’Issoire in Paris south, you might have had the same reaction, that he was a charming host who knew how to put people together. And if you were especially hungry that evening for whatever you could grab, that might have been as far as it went.

Haynes was an American who lived his adult life, close to 70 years of it, in Europe, much of it in Paris. Americans like to take credit for everything but some lives, even American ones, get lived elsewhere. By necessity.

I met Haynes numerous times after that, at his come-one come-all dinners and later around Paris. The man lived to 88, making a point to make friends. The biography of people he knew is a mile long, which acts as a kind of camouflage, because after reading all of it and being suitably impressed, you are still forced to wonder, Who the hell was this guy? Maybe we aren’t meant to know. Maybe he was determined to be a living embodiment of Deleuze and Guattari’s pure line of flight.

Touring Europe, Haynes wandered into the epochal events of Paris May ’68, participating in the takeover of the Théâtre Odeon, occupied by protesters then just as it is now. He settled in Paris, and formed an enduring association with the radical free university Paris 8 in the Bois de Vincennes, where he taught Media Studies and Sexual Politics for many years. That catches my eye, so I stay up all night reading and rereading an anthology of the Free Love movement which Jim did so much to advocate. More Romance, Less Romanticism has some great people in it, like Betty Dodson and Germaine Greer (both still among us) but from the cover onward I can’t make sense of its put downs of Romanticism, when they mean the soupy-silly technicolor version of perfect romance Americans pine for. The contributors, Haynes included, don’t have much to say about our economic civilization, they just dislike its constraints.

Not really a vision of how this new, non-possessive society might work, Romance and Haynes’ Hello I Love You ! is better appreciated as a generation’s orgasmic cry of Let me out ! directed at the elders and conformists who run the neatly designed jail of monogamy. « We have a duty to pleasure, » Haynes says in one of the many homemade films that document his life. A smiling disciple of Epicurus to the end.

Splitting his time between Paris and Amsterdam, Haynes, in the company of Greer and others, launched Suck, Europe’s first sexual freedom magazine, taking it to book fairs all over the continent. He later helped organize the first Wet Dreams film festival in the Dutch capital. Contrary to the banal clichés in circulation, it was hardly just a boys’ affair. Greer, both naked and clothed, made it clear that sexual liberation was very much for women.

Around the same time, in ’71, Haynes hooked up with Garry Davis, an ex-serviceman who, out of remorse for bombing Brandenburg during World War II, renounced his American citizenship and invented the World Passport. Davis is just the sort of person politicians and their hangers-on hate, constantly reminding them of their many failures. His short, disruptive speech at a U.N. General Assembly put it succinctly. "We, the people, want the peace which only a world government can give. The sovereign states you represent divide us and lead us to the abyss of total war." Alberts Einstein and Camus supported his efforts but, of course, no one’s heard of him in America. Someone had to do the putdown and it fell to Eleanor Roosevelt to mock his World Passport as a « flash-in-the-pan publicity » stunt. (Translation: pay no attention to the troublemaker mocking our relentless march to annihilation.) Haynes and Davis started manufacturing World Passports and opened their embassy in Haynes’ place on Tombe d’Issoire. They did business whenever anyone knocked, even in the middle of the night. (Who needs a passport in the middle of the night?) It sounds like awfully good fun – the passports got a few people out of jail and across borders – but authorities soon took notice and in ’74, the two men were on trial in Mulhouse, France, charged with counterfeiting and fraud and finally found guilty of Confusing the Public, a crime which, lamentably, they cannot claim all to themselves.

Throughout the Seventies and Eighties, Haynes traveled Europe relentlessly, publishing texts in defense of sexual freedom, a memorial for Henry Miller and poems by Ted Joans, a black American with whom he enjoyed a long friendship. If ever there was a poet who slipped between the cracks, whose life, lived between Europe and the States, needs greater attention, it’s Joans, and in 1980 Haynes founded Handshake Editions to bring out Duckbutter Poems. Meanwhile, to dive further into the history we all forgot, Dick Gregory, the comedian-raconteur, launched his own effort to free the hostages seized in the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution. Haynes was his go to man in Paris, on the phone with Teheran every day, as Gregory tried to do something politicians and diplomats couldn’t.

In ’79, the famous dinner gatherings started in what was already the most famous crash pad in Paris. They lasted for the better part of forty years, and from the biographies and advertisements scattered across the internet, you can see Haynes delighted in making connections between people. He was a guy who didn’t eat up the air all around him but gave everyone room.

That would be enough for most of us but in reality, it’s the second half of his European odyssey. It’s the part I learned first. Researching his life, I got the sense of Jim Haynes as the man on the spot, the born organizer, the genial wit who knew everyone and could pull almost anything together. I wasn’t too surprised when I found out that Haynes arrived in London in ’65, with an illustrious past already behind him, to run the Traverse Theatre. He produced Joe Orton’s Loot to acclaim, carried off the Whitbread Prize and gave Yoko One the stage for her first happening. Sonia Orwell (George’s widow) rented him a flat in her basement, while introducing the Charming American to the town’s artistic elite. London was already moving. It was about to start swinging.

Borrowing five hundred pounds from a Paris friend, he and a small band of cohorts founded The International Times. Pink Floyd and The Soft Machine played the opening night festivities. The IT, as it came to be known, is the mother of the underground press, different from the chapbooks dedicated to jazz or poetry, an actual newspaper with everybody in it. It ran for several years, a small miracle in itself. In ’67, finding two connected warehouses on Drury Lane, Haynes resigned from the Traverse and created The Arts Lab, an instant success that all cool Londoners wanted to visit, for the cinema in the basement, the art gallery on the main floor, the theatre. Haynes says, «My policy is to try to never say the word ‘no,’» and he doesn’t. As the playwright Steven Berkoff put it, « Every eccentric maverick lunatic individualist came to the Lab to lay his egg.» David Bowie rehearsed there. In 1969, unable to come to agreement with the City of London over rental, he and others squatted the empty Bell Hotel across the way. This may be the first-time artists seized abandoned buildings and put them to creative use, a practice which quickly spread to the continent and continues to this day.

Haynes was meeting everyone, saying yes to everything and keeping a social chameleon’s ledger. His journal entry for the end of ’67 reads simply, « Meet Hercules Bellville. Meet Dick Gregory and a long and warm friendship begins. Later I am his European Campaign Manager when he stands for President of the United States. Meet James Baldwin. Meet the American Ambassador to Great Britain, David Bruce, and his wife, Evangeline. Meet the Cuban Ambassador, Madame Alba Griñán. Am invited to dine with Brian Epstein and The Beatles. » Enough name dropping for one year, wouldn’t you say? Does Haynes have nothing to say about any of these people? This is 1967, a pivotal year, when Epstein committed suicide... plus a few million other matters of consequence. Character cameos are not Haynes’ forte. He’s an instigator, not a diarist and everything remains resolutely present tense.

If the Hippie Phase, like the Sexual Revolution that came after, collapsed under the weight of impossible objectives projected onto a society quite content with Business As Usual, movements aren’t really measured by success or failure, by those famous Lasting Changes people bang on about. It’s a question of giving human beings oxygen and ideals and letting them live their lives with a dose of freedom.

Of course, Haynes didn’t exactly arrive in London an unknown. Why follow the trail backwards like this? I want to excavate the life of the man I met in Paris, whose past he only slowly revealed, in anecdotes. He wasn’t a show off and he didn’t drone on endlessly about the fabulous ’60s.

In 1956, after drifting out of Louisiana State University, «the country club of the South» without a degree, Haynes enrolled in the Air Force, managing to finesse assignment to the U.S. base in Kirknewton, Scotland.

This is the moment that interests me, when so much is possible, when a human being’s antenna are up without knowing exactly what those marvelous possible things might be. It isn’t Haynes’ first trip to Europe but he’s on his own now, as if he’s standing on a moor, taking the long view through the clouds. He has to invent a life to go with his new-found freedom. Haynes didn’t waste time.

Within a few years, he’d done his military service, finished university and opened a bookstore in the Jekyll and Hyde-haunted stone labyrinth they call Edinburgh. The Paperback openly sold the still-banned Lady Chatterley’s Lover, as well as American imports the Village Voice and Evergreen Review.

A pious Presbyterian lady came around to purchase Lawrence’s novel, only to take it outside for a dramatic public burning. Scandal pays dividends of all kinds. Word got around and Haynes soon made the acquaintance of a portly Canadian with a family fortune in whiskey. He and John Calder ran thick as thieves and along with Ricky Demarco, they launched the original Traverse but not before giving Ubu Roi its UK premiere in a corner of the bookstore. Calder brought three French writers (Robbe-Grillet, Duras, Sarraute) to the Paperback where their willingness to talk about just about anything created a stir. Soon plans were afoot for a Writer’s Conference, which took place in 1962. The ground is shifting under everyone’s feet everywhere, and everyone wants to talk about it. Together they produced a line-up of writers that included Americans Mary McCarthy, Norman Mailer, Henry Miller and William Burroughs, Scots Hugh MacDiarmid, Muriel Spark, Edwin Morgan and Alexander Trocchi, as well as Lawrence Durrell, Stephen Spender, Rebecca West, among many others. The Conference was rife with open talk of drug use and gay sex, provided a grand huzza for Miller and launched Burrough’s career. It was inclusive, not exclusive, and overcame not only the objections of the staid Town Fathers, who were quite content with cozy classical music events. The 1962 festival, as inspiring as it was, was a distinctly different affair from today’s imitators, where it’s all about moving the merch, paying to hear an author for an hour before you’re hustled out the door with a signed copy. In ’62 there were day-long sessions dedicated to debate about Commitment, Censorship, Scottish Writing Today, The Novel and the Future, with parties into the wee hours...

Could Haynes have pulled off his lifelong escapade in the States? It’s not as if he, and everyone he worked with, didn’t face opposition along the way. The pressure to conform, to sell out, is just too strong in America. No, his life could only have been lived in Europe, among the European avant-garde with their openness to new ideas. Americans like to think they invented the Sixties, and maybe they did, in the form of a wandering American who criss-crossed Europe, opening doors and bringing people together for theater, for action, for sex and for life.

________________________________________________________

Jim Haynes and Ghédalia Tazartès were cremated at Père Lachaise within a few weeks of each other. Events celebrating the 1871 Commune of Paris at the Mur de Fédérés are now ongoing.

Tazartès quotes from interviews on electronicbeats.net (2012) and BOMB magazine (2017), plus translations from various French interviews. Thanks to the Jim Haynes Archive.

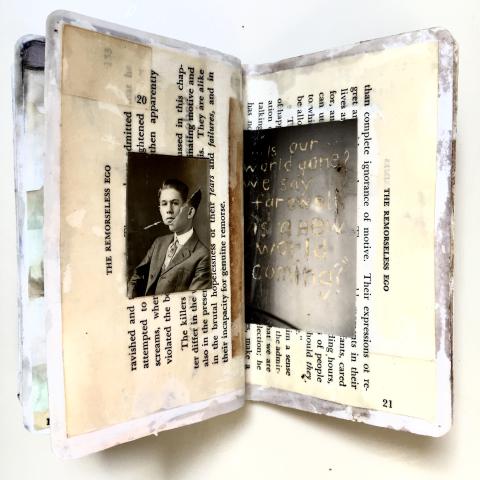

Photo credits: