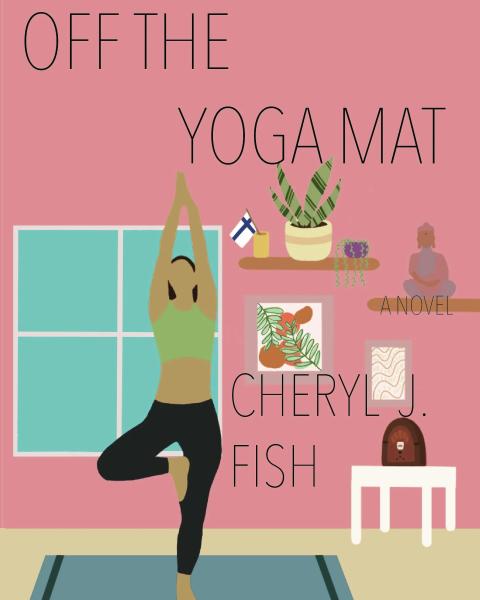

Excerpt from Off the Yoga Mat

Excerpt from OFF THE YOGA MAT © by Cheryl J. Fish

Forthcoming from Livingston Press/University of West Alabama, pub date Oct. 20, 2022

January, 1999

Chapter One “Inflexible”

Nate

“When others achieve success, how does that diminish you?” Nathaniel Dart didn’t care to consider this question from a talk-radio host. He was about to leave the apartment with a spasm in his back. His friend Gil, and his girlfriend Nora, had finally convinced him to take a trial yoga class in a studio a few blocks away. As he walked down Second Avenue with a slight shuffle, twinges running upward from his ass, the success of others gnawed away at him. A cash bonus Nora received at the end-of-the-year—she deserved the money for a job well done—but he hadn’t grabbed her around the waist or smiled in a swell of support. Nor had he taken her out to celebrate. And when Gil won a lottery for affordable housing nearby which meant more space and rent stabilization, of course Gil had the gall to rub it in his face, mentioning Nate’s dark studio apartment with moths burrowing in the closet. Nate had no choice but to resent him. One other victory throbbed against his bony vertebrate.

His old study-group mate Monica Portman landed a teaching job in Boston, a position that Nate should have applied for, could have applied for, if only he’d finished his thesis. He struggled to accept Ralph Waldo Emerson’s credo that “envy is ignorance.”

He stopped suddenly on his walk to watch dumpster divers pick through garbage bins outside the supermarket. They’d cook what was still edible, and someone shouted through a megaphone about the futility of waste in New York City. Determined to find freshness in what had been declared foul, the freegans sorted through packages past expiration dates, found perfectly decent bags of bagels and cookies and cut-up carrots. He heard them complain about tossing food with hungry and homeless folks everywhere. Nate felt disgusted by the vast inequalities in society; they mattered more than revising his thesis on jealousy as an evolutionary trait in humans.

Nate’s research combined a trifecta of disciplines: science, literature, psychology. It sounded loopy when he claimed the existence of a jealousy hormone. Not only did it benefit species studied by Charles Darwin, like those blue-footed boobies on Galapagos, but Homo sapiens as well. Envious rage might motivate men and women to loosen their desire for control. The result could turn out for the better. Yet jealousy was no walk in the park—it caused primitive rage and destruction which Nate witnessed everywhere. In his thesis, he proved his point by examining jealous characters in Shakespeare’s Othello and King Lear.

How does their success diminish me? He wished he could put that thought out of his mind. Nate spent countless hours in his swivel chair; one could say he lived where he sat.

In the yoga class, a tingling numbness ran down his legs, pain and trembling too. He stood in a darkish room with a yoga teacher asking them to bend from their core towards the floor. He couldn’t reach past his knees, his whole upper body as stiff at age 39 as if he were 50-something. I am not a yoga guy, he thought—I have more in common with the freegans. I should have never set foot in this dusty old hovel. He felt others staring at him.

Nate contemplated his future on all fours doing cow and cat, rounding his back like a feline, or should he flatten it like a bovine? Who named these postures? The students stood in unison, placing a bent leg along their thigh for tree pose. He grabbed a beam.

“Focus on one point on the wall,” said the teacher, a strikingly fit woman named Lulu Betancourt, who welcomed them warmly and insisted they obey their own bodies. “Take a three-part breath and be mindful. Let air seep out like a leaky balloon.”

Nate smirked. He visualized a giant balloon emptying with farting sounds. He filled his lungs then exhaled as told. Relaxation could wash over him.

She soon introduced them to the series “salute to the sun.” A set of flowing movements that started with standing, progressed to rolling to the floor, then rising into the cobra and plank positions with a rhythmic grace, ending with an upward curl, palms pressed together in gratitude. A subtle choreography he punctured with jerking motions. If Nate could reach an inch nearer to his toes and roll down without collapsing, he felt like he would celebrate. His version might be called parody, not salute. He was determined to modify his moves, like the barnacles, finches and beetles Darwin observed.

“Melt into the earth with a rushing sensation, rain drenching fields,” Lulu said in a soft yet determined voice. She leaned against the wall, bowed her head.

Nate tried to experience rain. Instead, he thought about money. He benefitted neither from the loopholes in capitalism that let the richest prosper, nor from a critique of its corruption. I am an academic serf living on rice and beans, he thought, and no one could care less. He was deep in debt from loans. He should apply for another fellowship or take an adjunct position at a City University campus. He wondered about the job referred to by his advisor Offendorf in his recent nasty note. Offendorf had scribbled dismissive comments on the pages it took Nate many months to write, and even more months to find the courage to mail to the university down in Maryland, with Nora’s goading. Offendorf had the nerve to reply:

WAY TOO MUCH time spent on Darwin. It may be trendy to consider evolutionary theory, but I don’t care for that approach. Take out feminism and limit psychoanalysis. You’ve inserted too many footnotes. Let’s put this baby to bed. When are you coming to campus? Bring the revision−we’ll talk defense date. Oh, and I might know of a teaching position.”

As Nate considered whether the job was real or just another one of Oppendorf’s bluffs, he was instructed to twist his torso, knee cutting across his folded leg. That evoked the twists and turns of Nora’s desire.

“Let’s conceive a millennial child,” she said. Nineteen-ninety-nine high stepped like a marching band through her ovaries. Fear of her upcoming, their upcoming, fortieth birthdays felt like annihilation.

“Nora. I can’t give you a baby now.”

“I knew you’d say that,” Nora said. “There’s never going to be a perfect time.”

“I’m not in the position to be a dad.”

“You’d be very loving.” She stroked his hand. “My salary can tide us over.”

His inability to care for a child felt like a character deficiency. He must finish his degree before procreating, not focus on the milestone of age forty. When his mom visited from Long Island the other day, she slipped him a wad of cash.

“Don’t say anything to your father.”

“You don’t have to keep doing this,” he said, feeling sheepish and small.

**

Nate’s spine cracked. Lulu headed over to his side during dandasana, a forward bend that segued into a seated wide-angle pose. She crouched. “Breathe into your stretch.” He noticed a beady-eyed frog tattoo near her shoulder—green and black, sinister. Lulu smelled of rose-oil.

“What’s wrong?” she whispered.

“I can’t concentrate.” What made her want to ink a frog into her skin?

“Observe your thoughts. They’ll dissipate.” She touched his head. “Probably.”

How should he respond to Offendorf’s reign of terror? Say “I need Darwin like Shakespeare needed Holinshed's Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland,” the source material for some of the Bard’s plays?

While Nate rested in child’s pose, head on mat, arms and legs compressed like a floating fetus, a surge of energy ran from the tips of his toes into his calves. So, what if Offendorf demanded he cut one-third of all he had written? How did their success diminish his? Disappointments acquired territory. One negative experience attracted others, expanding into new fiefdoms.

His old study group mate Monica Portman applied for everything. “I invented personal literary criticism,” she said, convinced of her pioneering role. Wasn’t she coming to town? As Nate struggled to pick himself off the floor for the next posture, it occurred to him: send her the very same pages Offendorf trashed and ask for a second opinion. Monica’s instincts resembled a baby sea turtle’s—born in sand, hurdling towards the ocean. He should trust her to guide him to safety.

Then yogi Lulu announced to the room “return to downward-facing dog.” He bent over, and placing his hands flat, stuck his butt in the air.