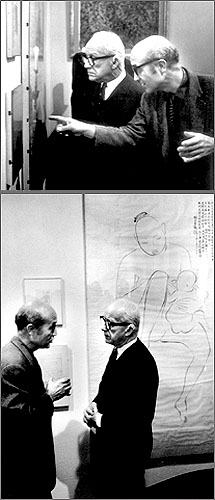

Buckminster Fuller and Isamu Noguchi

I recently went to the show at the Noguchi Museum called "Best of Friends," an exhibition chronicling the collaborations between Buckminster Fuller and Isamu Noguchi, and what struck me wasn't the work itself, but the sense of idealism that their work was based on, an idealism that permeated the culture of the time, and an idealism that now seems largely absent.

Fuller was born in New England, into an American utopian tradition whose roots went back to Emerson, Thoreau, and also Margaret Fuller, his great-aunt, an early feminist and co-founder of The Transcendentalist Magazine. By the early 1920s he was married, working with his architect father-in-law in the family business, but the utopian spirit remained latent in him until his daughter died of polio. Not long after that the business was sold out from under him - this was around the time of the depression, or what's called the "Great Depression," - and he found himself on the verge of bankruptcy. In the accounts I've read he walked out to the end of a pier and was about to commit suicide when something turned him around, turned him away from the past, and at that moment he determined, not only to make his own life a little different, but to make it possible for others, for the rest of the human race to live, not only differently, but better. "The possibility of doing good for any man," he said, "depends on the possibility of doing good for all men."

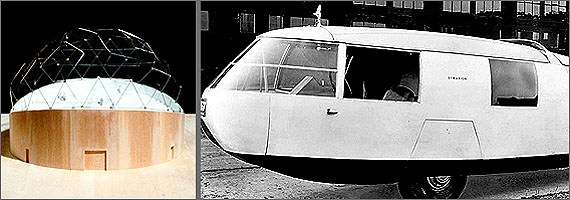

Fuller was a poet, a designer, a mathematician, and also a philosopher; he was one of those people out of whose head ideas seem to ceaselessly flow, and one of those ideas, was a house of the future. It was called The Dymaxion House. The word dymaxion - Dynamic, Maximum, Tension - was coined by an advertising man who worked for Marshall Field, where the house was first exhibited. For Fuller, it would be a house in which the tools of technology and science were used to make life, for the people who lived in it, better and safer and more organized.

He began talking about his house, giving "lectures" at a basement tavern in Greenwich Village called Romany Marie's. Artists and writers - including Arthur Dove and Edward Hopper, Stuart Davis, Arshile Gorky and Eugene O'Neill - would gather in the low-ceilinged room which was more a salon than a tavern. It was a place for the interchange and pollination of ideas, and it's where Fuller met Isamu Noguchi, in 1929. Fuller was a regular, and apparently quite a speaker, orating for hours while Noguchi, who was about ten years his younger, listened to him and was inspired by him. The two men became friends.

Noguchi had been living in Paris, on a Guggenheim Scholarship, where he'd studied with Constantin Brancusi. He was influenced by Brancusi, but because Noguchi spoke no French and Brancusi no English, their only language was the language of gesture. Now he was back in New York City, hungry for words and ideas, and what Fuller offered was the idea that art could be part of a possible utopia. The very act of friendship is a kind of attempt at utopia, and here were two dissimilar people who decided to makes things that would change the world. That was their bond, and it was manifested in 1933 when Fuller designed his Dymaxion Car.

Noguchi's, Challenger Memorial, Bayfront Park, Miami, Florida, 1985-1987. Noguchi's, Challenger Memorial, Bayfront Park, Miami, Florida, 1985-1987.The Dymaxion Car now looks quaint, as does the Dymaxion House, something out of a future that never materialized. In Fuller's inventions, in Noguchi's sculptures, in his designs for gardens and playgrounds, and even in his tables for Knoll and chairs for Herman Miller, there's an implied belief that hard edges and sharp corners, the dominant forms since the Industrial Revolution, were things of the past and would be replaced in the modern world by the forms of nature. "It is my desire to view nature through nature's eyes," Fuller said. He advocated a state in which "the artist has so thoroughly submerged himself in the study of the unity of nature as to truly become once more a part of nature." Nature was thought of as a model, something that we, as humans, were part of and linked to, and something that would indicate a direction for the future.

Bayfront Park, Miami, Florida, 1985-1987.

So there they were, these two men who shared a conviction that the world could be made better, but of course the world wasn't quite ready for the future they envisioned. Noguchi had to make life-like busts and statues to earn a living, and because of a rear-end collision, only three of Fuller's Dymaxion Cars were ever made. But still they persisted. Fuller went on to design Dymaxion Bathrooms and Dymaxion Maps, and to write several books. Noguchi designed playgrounds and public parks, and yes, he made sculptures, but he said, "Individual possession seems less significant than public enjoyment." I think he wanted his art work to be used.

Much of the space at the Noguchi Museum is devoted to the garden and the works of art that are part of the garden, including the benches and fountains. Not only is the garden very peaceful, but also the works of art seem more at home there, seem to belong there in a way they don't inside the museum walls. Architecture, in its broadest sense, is the creation of a space that interacts with people, and in the process of that interaction, physical meaning is given to the world. The abstract, organic sculptures in the museum garden, are more than objects to be looked at, they are objects that want to interact with the people who are walking by.

Noguchi was born in Los Angeles. Early on he moved with his mother to Japan, where he apprenticed himself to a Japanese house builder. And I think, as with Fuller, it was a house, or the idea of house, that became integral to the direction his life would take. With both men there's a striving after refuge, and safety, and even peace, a sense that maybe this abode or this structure or this habitat will be the space where our individuality is brought into union with the community of other human beings.

This brings me back to the tavern in Greenwich Village. I picture the two young, or youngish, men dreaming together at a stained wooden table in a noisy room off Washington Square. The times they were living in were dark times, darker perhaps than our own, but not dissimilar. They wanted to change the face of the world and they were preparing to do that. In the twenties, and even later, during the time of the atomic bomb and the Cold War, when Fuller was coming up with what he called tensegrity and designing his geodesic domes, and Noguchi was designing swimming pools and national monuments, there was still the possibility of improving the world.

Now, although there are still plenty of things to be done, plenty of changes that ought to be made, the future seems to have lost some of its allure. Now, in the age of commerce, in the age of wars and epidemics that seem rooted in commerce, we've just about lost our faith in the future. We've come to see it, not as a place of salvation, but as just another repetition of the past, another round of bad answers (that do nothing) to immaterial questions (that mean nothing). Where there used to be hope and the sense of possibility, now there's weariness and passivity. The idealism of Fuller and Noguchi lay in the future and the promise of possibility. We could stand a little of that idealism now, a little of the utopian spirit that gave them the courage to imagine a future in which the hands and minds of human beings might actually make the world better.

About the Noguchi Museum

Created by Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988), The Noguchi Museum opened in 1985, presenting a comprehensive collection of the artist's works in stone, metal, wood, and clay, as well as models for public projects and gardens, dance sets, and Akari Light Sculptures. The Museum — chartered as The Noguchi Museum — is housed in thirteen galleries within a converted factory building and encircles a garden containing major granite and basalt sculptures.

After a two-and-a-half year long renovation, the Museum re-opened in June 2004 with the addition of an education center, a new cafe and shop, more adequate handicap accessibility, and a heating and cooling system that allows the Museum to remain open year-round. Besides launching its first-ever program of temporary exhibitions, the Museum has created a special gallery devoted to Noguchi's celebrated work in interior design. Although the renovated Museum has a fresh look, great care has been taken to maintain the original character of the building, which was integral to Noguchi's vision for the Museum. The raw industrial space of the former photo-engraving plant serves as a superb backdrop for the artist's sculpture.

The Noguchi Museum offers a variety of education and public programs that seek to introduce the work and vision of Isamu Noguchi to diverse audiences. These programs encourage the investigation of Noguchi's work from different vantage points, and support participants as they experience the artist's work from their own perspectives. In addition to housing and exhibiting a collection of Noguchi's works, the Museum also serves the international art community by loaning works to other institutions for special exhibitions, organizing traveling exhibitions, and offering scholars access to the artist's extensive archives, including his records, correspondence, manuscripts, and photographs. The Museum also collaborates with The Isamu Noguchi Foundation in Japan.