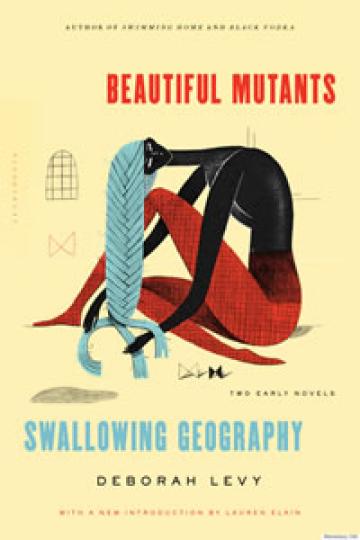

BEAUTIFUL MUTANTS / SWALLOWING GEOGRAPHY by Deborah Levy

Poet and playwright Deborah Levy staked out the territory of post-modern alienation with a vengeance in her first two novellas. 1989's Beautiful Mutants and 1993's Swallowing Geography (Bloomsbury) still thrum decades later with disdain for an increasingly confused free market world. Levy switches perspective and setting as if changing the channel, ceaselessly and compulsively searching for a transmission whose humanity hasn't been corroded. Her prose veers from dreamlike reverie to bald aggression in the turn of a sentence, never resting.

In Beautiful Mutants even the successes are casualties: the high-powered wealthy Banker is shaken at night by her sobs before arising to do her boutique shopping in the morning, while the rest of the characters labor in the lower ranks or drift aimlessly on the sidewalks. Being outside this value system doesn't result in meaning, and no escape seems on offer. The Anorexic Anarchist, the Poet, the Innocents: their individual withdrawal from the rat race makes them mere witnesses to its depredations. Around them the zoo burns with its animals turned to ash, a woman working on the 'meat belt' in a processing factory loses her hand, the macabre and the lyrical pile up and cry out with urgency. Lapinski, an immigrant to London from the Soviet Union, sits at the center of this whirlwind, seemingly undaunted by the cold calculations of her former friend the Banker or the hallucinogenic statements of the Poet or the violent misogyny of her upstairs neighbor. Her world is a sequence of impressions, and Lapinski's power resides in her ability to accept that there is no rhyme or reason to them.

Swallowing Geography centers on the writer J.K., another woman at home with uncertainty. A nomad on assignment, not even her lovers are given access to who she truly is. The one connection of any authenticity is with an old friend dying of AIDS, who writes to her from his sickbed as he recedes from the world that she is wandering. The news blares against the backdrop of his letters, broadcasting the breakup of the USSR and the offensives of the Gulf War, and J.K. imagines the young men at war in the desert as she passes from airport lounge to distant hotel. She dreams of taking root in a place only to pack her bags again, as if the geopolitical turbulence elsewhere has infiltrated her own psyche.

Levy captures an era whose logic is still with us today: winner-take-all capitalism with no spoils for the lower classes and increasing, pointless consumerism at the top, a continuing military presence, even a lingering opposition of East and West. Individuals are an afterthought, powerless in their limited sphere and increasingly unable to anchor themselves in a firm identity. Levy's works are also markedly feminist, not through a strident declaration but in the markedly small role given to romance in the lives of Levy's narrators. Men appear as neighbors, as friends, and occasionally as objects of desire or scorn, but there is no room amidst the complications of life for anything so boring as a marriage plot or even more than a passing affair, inevitably abandoned. Her characters, while having a strongly sexual side, define themselves on their own terms to a degree that remains relatively rare. Perhaps the difficulty of establishing a conventional, settled, content life has this as its upside: that no one can hold you to an image of who you ought to be. Bloomsbury's re-issue of these two works together allows for a deeper appreciation of Levy's distinctive sensibility, unsettling though it is.

Deborah Levy's family emigrated to London from apartheid South Africa when she was young. A poet and playwright as well as a novelist, her recent book Swimming Home was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize.