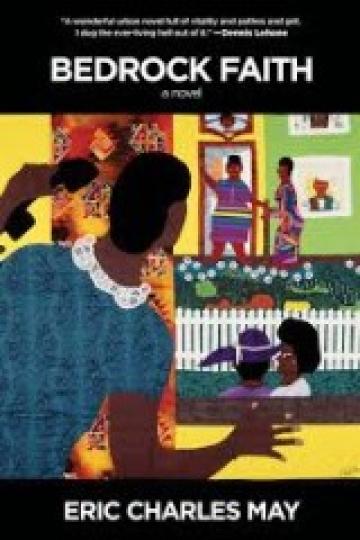

BEDROCK FAITH by Eric Charles May

Was there ever a better guarantee to the reader than an author’s connection with place? Eric Charles May’s Bedrock Faith (Akashic Books) presents in fictional South Side Chicago neighborhood Parkland a town that stands as a character in its own right and a loving tribute to his city. Each particular of this historically black township’s orientation is meticulously cataloged, from the precise turns to take off the expressway to the exact confines of its borders and the shops lining Main Street. Founded in the 1870s by black settlers, Parkland is a neighborhood with a strong sense of its own identity, to the point of having a reputation for ‘vainglory.’ Crime-free and church-going, with a small-town’s endless appetite for gossip, May uses Parkland’s sense of historical pride as a vehicle for probing Chicago’s racial fault lines—interlopers such as police and firefighters are immediately labeled as Black or White. Yet there is no whiff of the polemic in this debut. Finely observed, it creates a vivid, rich picture of a small community shaken by an unwelcome disruption.

Stew Pot Reeves is the cause of Parkland’s palpitations, newly returned to his mother’s house on 129th street after a long stint in prison. He rejoins a block whose idyllic community life covers a multitude of secrets with fault lines and factions of long-standing. There is Mrs. Butler, a judgmental black power radical raising her grandson alone; Mr. Davenport, the self-important block president with an unfaithful past, an alcoholic wife, and a jaded teenage daughter; closeted, attractive Erma, desired by many of the men on the block and uninterested in any of them; jovial, irreligious Mrs. Hicks; war veteran Mr. McTeer, who has pined for his neighbor Mrs. Motley since before they were both widowed; and lastly Mrs. Motley herself, a retired librarian who encounters Stew Pot first on his return.

A teenage delinquent before his arrest on sexual assault charges over a decade before, Stew Pot was widely held responsible for a range of neighborhood scandals, from the burning of Mrs. Motley’s garage to the murder of a neighbor’s cat. His past makes Mrs. Motley wary of Stew Pot’s claim to have found Jesus in prison, but when he appears at her door to ask for a bible it seems too unchristian to refuse the request. Unfortunately the conversion seems all too genuine: first his mother’s soul and pop albums and her ‘immodest’ clothes are tossed out, and next Stew Pot focuses on bringing others into the Light, or punishing them for any errant behavior. From outing Erma’s sexuality (thereby driving her out of Parkland) and spreading the private diary of Mr. Davenport’s irreverently observant daughter, to attacking Mrs. Hicks’ harmless ‘Christmas in July’ party as pagan and later interrupting her funeral service, to confessing paternity of Mrs. Butler’s grandson, Stew Pot’s unchecked, maniacal ‘witnessing’ wrecks the lives of one family after another. In return his presence in Parkland is shown to be more and more overtly unwanted: a neighbor runs over his beloved pit bull, his house is defaced, he is wrongly blamed for yet another arson on Mrs. Motley’s property, and, in the worst blow of all, his own mother and his spiritual leader from prison leave him to marry and go on an evangelical mission.

The reaction at Parkland to these setbacks is barely disguised glee. Only Mrs. Motley refrains from outright demonizing Stew Pot, despite the fact that his cruelty to her best friend Mrs. Hicks effectively drove her to an early grave. Stew Pot himself holds Mrs. Motley in such high esteem that when he is arrested again, this time for the murder of his original assault victim, he writes to her from prison. Tormented by his past and mentally ill, Stew Pot is beyond saving by Mrs. Motley or anyone else, but others are drawn to her unostentatious virtue as well, from her suitor Mr. McTeer to his rival, a local politician who has also been wooing Mrs. Motley for years. A member of the ‘Old Guard’ at her local church, she scrupulously follows an inherited code of honor, not to mention observing all of the civilized traditions she was taught at finishing school.

Indeed, Mrs. Motley is a creation the likes of whom many authors only dream of achieving, and whose company could easily be enjoyed over several more books. In fact, Bedrock Faith succeeds in no small part because it shares many of Mrs. Motley’s finest attributes. The novel treats all its characters with her even-handed fairness, and shares with her an attention to detail in the smallest matters, as when she dresses for even a day at home in the most proper silk blouse, pencil skirt and stockings, or when she forgoes the convenience of Tupperware when delivering dinner across the street to Mr. McTeer on a formal china plate bearing “the sort of food his wife had often dismissed as ‘common.’”

While it may not be innovative or experimental fare, this novel’s joys are a strong argument for the under-appreciated virtues of “common.” Unfolding in time with the rhythms of a Chicago neighborhood, it presents both the benefits and the flaws of a small, rumor-happy community. Stew Pot lives up to his name in stirring the ingredients together, but the unspoken resentments and tacitly ignored private troubles that drive the dramatic events he sets in motion are not in themselves of his making. For all that Stew Pot is oblivious to the possibility that there are many paths to the Light, and many ways of perceiving it, his neighbors have often made their own compromises, preferring to present a facade for the world than to admit to the truth of their own situation. It is a gifted author who can show us such three-dimensional characters and make them come to life. Hopefully it will not be the last time that May visits with the residents of Parkland.

Eric Charles May is an associate professor in the Fiction Writing at Columbia College Chicago. A Chicago native and former reporter for the Washington Post, his fiction has appeared in the magazines Fish Stories, F, and Criminal Class. In addition to his Post reporting, his nonfiction has appeared in Sport Literate, the Chicago Tribune, and the personal essay anthology Briefly Knocked Unconscious by a Low-Flying Duck. Bedrock Faith is his first novel.