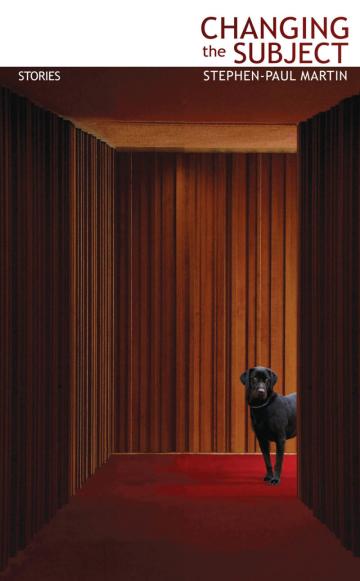

Changing the Subject

If his new short story collection Changing the Subject has an ambitious title, Stephen-Paul Martin gets away with it. And it's not only because of his change-ups between eco-terrorism, women with nice teeth, dogs, Macbeth, various assassinations of President Bush, and animated billboards depicting Custer taking Tylenol before his last stand.Each of the six stories employs the phrase “changing the subject” differently as Martin examines his characters' subjectivities.

Harry Knight felt anxious, thought of changing the subject, then realized that he wasn't sure what the subject was, unless it was change itself, which case changing the subject would be an example of the subject, and would only make his anxiety worse.

Martin's investigations of subjectivity include the experience of perception, subjection to culturally imposed limits, and the subjective truths of alternate interpretive skills:

I say: That was pretty weird. I felt like my first-person singular sense of myself was floating about an inch in front of my face, like a small transparent balloon.Craig says: That's what I felt too. Though to me it seemed like the first-person pronoun was the dripping of a leaky faucet somewhere behind my head.I say: Do you think those guys at the next table had anything to do with it?Craig says: They sound pretty messed up. Maybe they work for an advertising firm or a TV station, and they're in the business of stealing people's identities. They want us to forget who we are so they can tell us who we are.I say: Or maybe they're just the kind of New Age weirdos that tend to hang out in places like this.

The collection's deadpan tone makes it more surprising when its worlds bulge surreally. In the beginning, it's quiet, almost naturalistic:

I ran my hands across my face to make sure it was mine. Then I looked quickly around the room to make sure no one had seen what I was doing. All the other people in the room were touching their faces, looking around to make sure no one had seen what they were doing.

But Martin sequentially builds a vocabulary of in-jokes and non sequiturs along with his pattern of intrusion into the narrative. This can seem crude:

Something told me to leave as fast as I could. But something else told me to go upstairs.

Later the reader no longer sees the intrusion so clearly. Some narrators gripe that they're in “a story no one seems to be telling,” while others grumble:

It really does feel like I'm being controlled by something else, something that's pretending to be me, telling me what I think and want and what I should do about it.

As is often the case in subjective reality, time misbehaves and ridiculous tangents are taken. There are repetitious delicious double cheeseburgers and cravings for them, derisive comments about cell phone users (“phonies”), and even repetitious repetition itself:

I sat and stared into the distance. Thirty minutes passed. The words that were telling me what I was thinking went backwards. The same thirty minutes passed again. The words that were telling me what I was thinking went backwards. The same thirty minutes passed again. For less than a second I became a tall cactus on a ridge thirty yards to my left.

The protagonist of “Food,” Professor Food, asserts that full understanding can only be achieved through repetition, that things change with each iteration, and that “it's crucial for students to learn to cope with annoyance.” He gives the same lecture every class in which he states

that all reading is misreading, that the best we can do is accept that we're misreading everything, a claim that pissed off the finance major when Professor Food made it in his opening lecture a few weeks before, but now the finance major finds it comforting, since it means that mind readers like Professor Food will always be wrong, reading their own concerns and tendencies into what they think they know, never seeing beyond themselves, but the comfort fades when the finance major begins to misread his own thoughts, an absurdity that's upsetting at first, but soon begins to seem funny . . .

As Food chastens the reader, Martin's consciousness is visible behind the text. He takes on the reader's task and criticizes himself:

Professor Food is only trashing specialized expertise because he's insecure about his own expertise, because he can't quite master the subject he claims to know best, so instead he's mastered ways of changing the subject . . .

In “Refusal as a Radical Act,” Martin includes an article in the New York Times Book Review – a bitter attack on a fictitious account of President Bush's capture, disfigurement, and installment in Abu Ghraib by a group of radical activists. The narrator remarks that the critic

is working against his own purposes. In effect, he's publicizing the book's anti-war message by denouncing it in such a visible place. I'd be surprised if the book didn't become a New York Times bestseller. This leads me to suspect a hoax.

Similarly, Changing the Subject is so self-reflexive that any review trashing it is already inscribed within it – not that I expect anyone who reads it to trash it, with the possible exception of the Presidents Bush. What is most difficult to communicate here, despite all of my block quotations, is the simplicity and originality of Martin's language. Inevitably, maybe, for a book of so many dislocated subjectivities, Martin himself describes his accomplishment best:

It was language in its most visionary sense, conjuring its own worlds, refusing to subordinate itself to the so-called realistic task of describing or addressing what people had been trained to call society or nature.

Stephen-Paul Martin is the author of over twenty books of fiction, poetry, and non-fiction, including The Gothic Twilight and The Possibility of Music.

Marina Read Weiss studied English and creative writing at Amherst College, and lives in Brooklyn. Her poetry and criticism can be found or are forthcoming in 34th Parallel, Boston Review, Brink Magazine, Caper Literary Journal, Clapboard House, Explosion-Proof*, and elsewhere. She received a Fulbright in 2008.

Marina Read Weiss studied English and creative writing at Amherst College, and lives in Brooklyn. Her poetry and criticism can be found or are forthcoming in 34th Parallel, Boston Review, Brink Magazine, Caper Literary Journal, Clapboard House, Explosion-Proof*, and elsewhere. She received a Fulbright in 2008.