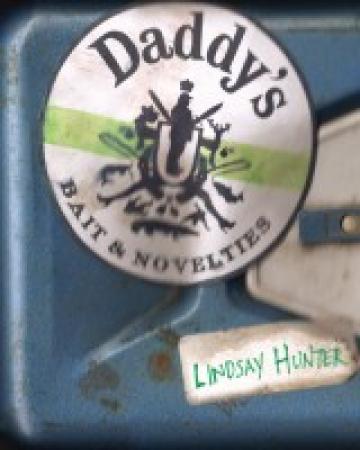

Daddy's

Despite Lindsay Hunter's decision to name her new book Daddy's, there are more than just fathers stalking, squalling, seducing and suffering in these 210 sordid little pages. That being said, Daddies certainly do make an appearance – in fact the clever, possessive title should give the reader an inkling as to what lies ahead. In these “24 fictions” many characters (male and female alike) are decidedly consumed by their fathers – both literally, in ambiguously miserable dealings, and metaphysically, through long-tentacled memories groping, groping with their tainted touch.

In the second story in the collection, “Scales,” the reader encounters a pair of adolescent girls struggling in their bodily self-loathing, one overweight, one so painfully thin “little shadows collect under the bones” of her spine. Passing a joint on an overcast day, the girls gather their limbs onto the couch to watch T.V. Amid a pile or Doritos, diet coke and spray cheese, the fatty of the two friends stuffs the plastic-flavored nibblings down her gullet until she's glutted with neon cheese and carbonated sugar:

I eat until I can't eat anymore. I'm done I tell her. Okay she says. Good. She puts the tray on the floor and scoots closer. I give her my hand and she sucks my fingers clean. The thunder is so loud it drowns out the television but I watch it anywayâÅ_¯a talk show, a woman openly sobbing, a child stunned by the lights, the host stabbing the microphone into the audience. Who has something to say? Say something, say something...She leans in and kisses me, licking my lips, probing my mouth for bits of food, sucking my tongue.

Wayward adolescents, wrestling with all the (in)glorious troubles of burgeoning bodies, confounded minds and confined spaces are found within the aptly named tale “Fifteen” as well. We all knew those mothers who were too laissez-faire in their rearings, allowing anything and everything to transpire amid a blurry wash of blue cocktails in a cracked blender:

In the corner of Tina's mama's apartment there were little piles of things. Tiny shrines to catshit and dryer lint and wrappers for condoms candy beer-bottles toilet paper lipstick-tubes and various electronics...Katie was asleep with her mouth open but Joey got in there and slurped away. Later we'd call Joey Slurpee and he'd punch a wall over it, not least because it was Katie who he'd been kissing, Katie who ate a ashtray and had a uniboob and a mouth with twice the teeth everybody else had, all coated with a sheen of butter...In the morning our mamas would pick us up while Tina's mama flipped pancakes to mask the scent of barf and smoke...and life smelled like peach carpet spray and cinnamon chewing gum and cheap-flavored wine, all backwashed up.

Children aren't the only ones thrown into the chum bucket, oh no. In one of Hunter's longer pieces, “The Fence,” a wife whose husband fucks her quite a bitâÅ_¯perhaps most notably on the kitchen floor, their sweaty faces glinting in the obsidian black oven door âÅ_¯remains utterly unsatiated, and seeks out her own private (and painful) pleasures. Clutching her dog's collar against her pussy she shocks her herself again and again with the electrical fence:

...I have my favorite corner, right where the gravel driveway stops and the grass starts, where I can see the road and if I stretch I can touch our mailbox...the jolt is delivered. Like a million ants biting. Like teeth. Like the G-spot exists. Like a tiny knife, a precise pinch...My underwear is flooded with perfect warmth. I lie back in the grass and see stars.

Pain and pleasure are coupled tightly in much of Hunter's work, especially in “Love Song,” where a lush of a father takes his daughter out on the town into the bowels of Ruby Tuesday's and Gator's, “Daddy's favorite establishment,” for her birthday.

As we parked he belched my name, drawing it out, something that I used to love, then he added I planned something real special for you on your special day, his breath going out at the last word, sounding wet...Daddy ordered a double whiskey...and when the waitress wandered off he presented me with a Ziploc of quarters. Happy Birthday sweetness, he said. That's enough for at least two games of eight-ball if you can stand it.

Eventually the birthday girl drives him home and leaves the lolling sod in his apartment. But just when you're poised for another perversion, girding your loins against the impending sorrow, Hunter leaves us lingering with optimism, with a glinting glimpse of beauty and we're reminded that without the ugly, there is no such thing as beauty at all.

But see then when the bus come I seen what Daddy meant about things at night looking different, to look at it the bus some kind of miracle box of light trundling toward me with an offering of strangers and a lungful of air conditioning and a bell I could ring any time I wanted to, to make it stop...

Hunter deftly toggles between these tales of cruel youth, crumbling marriages, anorexia, obesity, masochistic masturbation and alcoholic daddies. But Daddy's remains a bit unreconciled; it's a rather schizophrenic work. The reader is left a little raw with all foreplay, no follow-through. Just when you start sinking your teeth into a narrative, the story ends, forcing us to imagine what came before and will transpire after.

Still, these sinister vignettes flash hot and bright, speckled with filth like a subway car darting into a tunnel. And Hunter's tone is nuanced, vacillating between colloquial realism and smooth gusts of whimsy, achieving a lyrical quality with a sharp edge, slicing you sweetly.

If Hunter's prose isn't enough to surface a few pink-swollen scars in your cerebrum, perhaps the illustrations will; each story is accompanied by a gritty black and white photograph âÅ_¯anything and everything that could live in Daddy's tackle box including torn tarot cards, rain-soaked cigarettes and a few chewed chicken bones. But like any tackle box, laden with hooks, lures and gutted drippings, the reader will be pleased to close it for a while before casting the line that way again âÅ_¯ it'll take a while to wash away all that sorrow.

Lindsay Hunter is the co-host of a flash-fiction reading series called Quickies. Daddy's is her first book. She lives in Chicago.

McGrath Tandy is a writer living in San Francisco, working as an editor for an interior design trade publication. She holds a Master's in 20th Century Literature from Brooklyn College (wildly useful) and is currently working on a memoir.

McGrath Tandy is a writer living in San Francisco, working as an editor for an interior design trade publication. She holds a Master's in 20th Century Literature from Brooklyn College (wildly useful) and is currently working on a memoir.