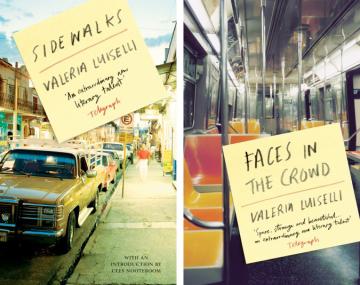

FACES IN THE CROWD / SIDEWALKS by Valeria Luiselli

Note: Images link to Valeria's Amazon page; links to the individual books are below, in the first sentence of the article.

Valeria Luiselli's Faces in the Crowd, a novel, and Sidewalks, a sequence of essays, have been published simultaneously by Coffee House Press, like components of a single project, and have a combined weight that dwarfs the already considerable gravity they have individually. Sidewalks is a daisy chain of essays dealing centrally with the idea of space. The most intoxicating of the ideas Luiselli presents almost seems like the prelude to a new school of literary thought. She refers to writing as the crafting of relingos, which means the unoccupied, unused space in a city. An example of one of these is an island of grass in the middle of a highway bypass. “A writer is a person who distributes silences and empty spaces,” she declares at the end of the essay.

It's an odd idea, which can be easily dismissed as poetic flourish if she doesn't demonstrate it. It is reminiscent of Sloterdijk's idea of the interfacial space, which is technically empty, but filled with the ideas and emotions that are reflected between either side of the space. A relingo is the space where the city ceases to exist, but which exists within the city's boundaries. It can be a quiet place, perhaps only occupied by stray cats or litter, or a place awash in the noise of the city around it. Standing in these spaces is alienating. Outside of the city, one is reduced to the state of being an observer. The city forgets them, and its absence is what fills the space. So it is, says Luiselli, with writing.

But this is only a small moment in a larger work, and it's almost buried, for Sidewalks is not a philosophical treatise, but a collection of personal reflections. At times it resembles something of a 'chopped and screwed' rendering of Karl Ove Knausgaard. It is as personal, honest, and wild as some of My Struggle's most hypnotic passages, but Luiselli's voice is distinct, and her concerns are uniquely Luisellian. Space, death, cartography, and the imposition of the city are woven together into what amounts to a portrait of a writer's mind rather than a memoir.These ideas flow naturally into Faces in the Crowd, which can be seen as part novel and part proof-of-concept on the mission statement she provides in Sidewalks. Faces in the Crowd is a physical artifact of life in New York City.

It is told in a succession of tiny episodes telling three distinct narratives. Luiselli calls it “a vertical novel, told horizontally.” Ostensibly it is about a woman, presumably the author, living in New York and plagiarizing translations of a forgotten Mexican poet, Gilberto Owen. This narrative is sandwiched between an account of the same woman writing that story as a novel, and Gilberto Owen's diary of his own time in New York City, living in the same apartment that his plagiarizer would years later. It's this final strain of narrative that eventually eclipses both of the others (though where exactly in the book that occurs is hard to say).

It reads like an epistolary novel with all of the pages scattered all over the floor, and the reader is crawling through them. Or three separate diaries mixed together as a result of some accident at the printers. At one point, Luiselli declares her intention to write “a silent novel, so that it doesn't wake the children.” It's uncanny how close to that she hewed. Reading the novel is the same as forgetting it. You come out on the other side of reading it with an indelible impression, a sense of its geography and architecture, but mostly with its absence, begging for it to be read again. The brevity of each of the episodes, and the speed to which they are flung at the reader obscures them, like an express train rushing past crowded subway stops. The colors are felt but all of the specifics of the stations get lost in the remembering. Or like the relingos a car might whoosh by on the highway.

In Faces in the Crowd, the author returns to her window again and again to watch her neighbor across the alley eat dinner, shower, and eventually go to sleep and turn off all the lights. She dreams about what his life contains, and comments about how it's fitting that when we turn on our lights at night, we can't see out into the world, but only our own reflections in the window. She watches her neighbor with the lights off, and it's somewhat telling that she never closes her curtains or turns on the lights.What is something new in literature? In one sense, it is when something that wasn't present in the cultural conversation is added. That thing could be very old, but simply uncounted up until its inclusion. Karl Ove Knausgaard's My Struggle, for example, adds Karl Ove Knausgaard to the conversation. Luiselli, also new, is like us, lights off, watching her neighbor through an open window. What she adds to the conversation is quietness.

Valeria Luiselli was born in Mexico City in 1983 and grew up in South Africa. Her novels and essays have been translated into many languages and her work has appeared in publications including the New York Times, Granta, and McSweeney's. Some of her recent projects include a ballet libretto for the choreographer Christopher Wheeldon, performed by the New York City Ballet in Lincoln Center in 2010; a pedestrian sound installation for the Serpentine Gallery in London; and a novella in installments for workers in a juice factory in Mexico. She lives in New York City.