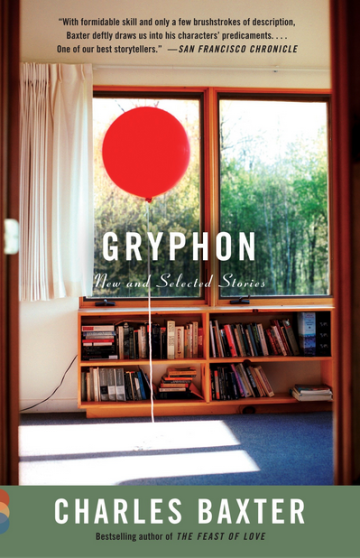

Gryphon

When I see “New and Selected Stories” on the cover of a book, I usually cringe. Regardless of the merit of the individual fictions within, such a retrospective work generally amounts to the literary equivalent of a “Greatest Hits” album, a self-congratulatory TV series ending clip show, a lifetime achievement award given, with much pomp and ceremony, to oneself. The aim is to step back and admire, not to plunge headlong, to conclude rather than to question. Though it includes twenty-three stories, the oldest dating back to the early 1980's and about half previously collected elsewhere, Gryphon by Charles Baxter is a rare exception to this rule, for the simple reason that its author seems constitutionally averse to summing anything up.I first encountered Baxter's work when I read his exceptional collection of essays on literature, Burning Down the House, which includes in it his wry and spot-on dissection of Stunning Realizations in fiction, “Against Epiphanies.” In it, he writes,

The loss of innocence is partly a recognition that there are depths to things, that what you see is not always what you get. The pathos of this discovery is well known, especially among Americans and adolescents... A belief that one is a victim will lead inevitably to an obsession with insight.

The connection between the epiphanic story and the coming-of-age story isn't just a historical one, going back to Joyce's “Araby”; it's inherent in their structures. Whether or not the protagonist of an epiphanic story is actually young, the focus is on his lack of self-awareness, his passivity and innocence (or ignorance). The problem is always that he doesn't yet know any better, the defining quality of child- and victimhood both. And the narrative presupposes a curative truth: his education, be it moral or spiritual or philosophical. As Baxter points out, there's nothing fundamentally wrong with writing about characters in this state. But what about the rest of us – graduates, drop-outs, recidivists, unbelievers – people who do know better, who have only themselves to blame? In other words, what about adults? Is there a place for them in the modern short story? Gryphon says yes.

Throughout Gryphon, many of the most fascinating characters are the most over-educated. In “Winter Journey,” an early piece originally collected in Through the Safety Net, the protagonist Harrelson (“perpetual PhD student, poverty-stricken dissertation nonfinisher, academic man of all work”), drives drunk through a snowstorm to pick up his soon-to-be-ex fiancee from the gas station where she's stranded. In the first paragraph, Harrelson gazes out the window: “Harrelson sees the snow symbolically. Somehow it represents his refusal to sell out.” Midway through the story, passed out at the wheel of his car, he “wakes up, full of the intuition that his life is a disaster.”

We soon learn, too, that he has “familiars in the spirit world,” guardian angels to whom he prays almost constantly. Yet though Harrelson leaps from one moment of radiance to another, nothing is illuminated. No path presents itself. Near the end, even death reveals itself to be just one false hope among many: “Harrelson has a premonition that he may not live for long. With what resistance he has left, he dismisses the idea as weakness, a bout of self-pity.” In the story “Poor Devil,” collected for the first time here, a divorced couple, in the last stages of cleaning out the house where they lived during their marriage, fall into a conversation about all the secret parts of themselves they never shared during their relationship. “My general ignorance of her character causes her sorrow, she now admits,” the narrator tells us. “She wonders whether I was deluded about women in general and her in particular. To illustrate what I don't know about her, she begins to tell me a story.”

Wife and husband each in turn relate episodes from their pasts in a manner very reminiscent of Joyce's “The Dead,” and the narrative trajectory appears headed in the direction of transformative insight – until the final section, when Emily, the wife, suggests they walk through the night-dark house with their eyes shut, just to see if they still can find their way around.

It's right about then that I'm back in the living room, and I bump up against Emily, whose arms also have been out, in this game we're playing. In the story that I don't tell, we excuse ourselves, but then, very slowly and tenderly, we are inspired by each other at last, and we take each other in our arms, and all the bad times fall away... That's the story I don't tell, because it doesn't happen, and couldn't, and would not, because I am unforgivable, and so is she. Two poor devils: what we don't feel is remorse.

The problem in this marriage, wasn't, after all, that the two people didn't know each other; it's that they didn't care. And no amount of new knowledge can absolve them for that.

Even the title story, told from the point of view of a fourth-grader, diverges from the traditional coming-of-age/epiphanic arc. Miss Ferenczi, a substitute teacher, offers her students a world of “substitute fact,” where six times eleven equals sixty-eight and half-eagle, half-lion beasts dwell in circus cages. One would expect such a figure to inspire her students, opening doors for them into realms of imagination and mystery, challenging them to reach beyond the narrow sphere of their small town. Yet Miss Ferenczi does the opposite: on what turns out to be her last day in the classroom, she reads the children's fortunes from a pack of tarot cards, making a series of damningly plausible predictions. “Not bad,” she says of one little girl's cards. “I do not see much higher education. Probably an early marriage... There's something bleak and dreary here, but I can't tell what.” She tells a little boy, “You might go into the army. Not much romantic interest here. A late marriage, if at all.”

The myth of education is that it broadens one's horizons – in fact, the students are studying from a textbook titled Broad Horizons. But the “facts” that hold the children rapt in Miss Ferenczi's classroom are anomalous, useless, confusing, disconnected from everyday life and reality. Even she does not believe that revelation can save them from their fates.I realize that this description may make Baxter's vision of the world sound depressing. Yet I don't find it that way at all. What his work rejects is not the possibility of love, or contentment, or even joy, but easy answers. In the story “Shelter,” a young husband and father faces the guilt of finding security and home in a world where so many are unmoored. In “Ghosts,” a young mother has to turn away from her aging, post-stroke father to make a healthy life for herself and her son. In “Mr. Scary,” a happily married grandmother secretly admits to herself about her husband, “[S]he was bored by people like him... But it was boredom that had the staying power.” When Baxter's characters are happy, they are happy in spite of what they know, not because of it. And for that reason, their happiness is as impermanent, unsure, and gorgeously true as anything can be in the substitute reality of fiction.

Charles Baxter is the author of the books Shadow Play, The Feast of Love, and Believers, among many others. His website is http://www.charlesbaxter.com.

Charles Baxter is the author of the books Shadow Play, The Feast of Love, and Believers, among many others. His website is http://www.charlesbaxter.com.

Chandler Klang Smith's genre-bending novel The Sky Is Yours (Hogarth/Penguin RH, 2018) was listed as a best book of 2018 by The Wall Street Journal, New York Public Library, Locus, LitHub, Mental Floss, and NPR, which described it as "a wickedly satirical synthesis that underlines just how fractured our own realities can be during periods of fear, unrest, inequality and instability." Chandler has an MFA in creative writing from Columbia University. She has served twice as a juror for the Shirley Jackson Awards, worked in book publishing and as a ghostwriter, and currently teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College.

Chandler Klang Smith's genre-bending novel The Sky Is Yours (Hogarth/Penguin RH, 2018) was listed as a best book of 2018 by The Wall Street Journal, New York Public Library, Locus, LitHub, Mental Floss, and NPR, which described it as "a wickedly satirical synthesis that underlines just how fractured our own realities can be during periods of fear, unrest, inequality and instability." Chandler has an MFA in creative writing from Columbia University. She has served twice as a juror for the Shirley Jackson Awards, worked in book publishing and as a ghostwriter, and currently teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College.