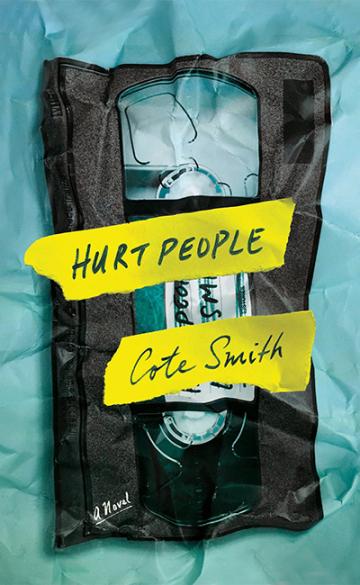

HURT PEOPLE by Cote Smith

It is no surprise to find Cote Smith's debut novel, Hurt People, published under the FSG Originals imprint, which has a penchant for tales from the dark underbelly of America. Among the ominous landscapes drawn by FSG authors such as Frank Bill and Amelia Gray, Smith's hometown of Leavenworth, Kansas fits right in, with its prisons looming over the novel like watchful guards. Opportunity, here in the center of a prison industrial complex, is a chance at catching an escaped convict, while seemingly the only entertainments on offer are rented movies, darts, and boxed wine. This setting is depicted through the eyes of a pre-adolescent younger sibling with a matter-of-factness that cannot but inspire the sympathy of the reader; not old enough to know what he is missing out on, he takes his surroundings for granted while knowing on some level they could be better. The nice suburban house his family lived in before a divorce sends him, his mom, and older brother to a ramshackle apartment across town serves like a long-lost vision of the American Dream.

For Smith's nameless pre-adolescent narrator and his slightly older brother, the summer recreation of choice is sneaking out to their dingy apartment complex's pool in direct disobedience of their overworked, lonely mother's orders. Against a backdrop of tornado sirens and escapee alarms, the eldest brother comes increasingly under the spell of Chris, a young man who loiters by the pool in wait of unsuspecting boys just like themselves. Oblivious to the growing threat to their sons, both parents increasingly withdraw into problems relating to their dissolved marriage; meanwhile, the quality of attention paid towards their sons ranges from distracted to negligent. The siblings' bond frays under the strain, and the younger brother watches helplessly as he finds himself excluded from the secret relationship between his brother and new older friend. The inattention of their parents alternates with sporadic and unsuccessful efforts at discipline, and it becomes clear that their own unreliable behavior is the cause of a brewing rebellion amongst the brothers. All of these family dynamics are carefully, empathetically drawn, and amplified by the mother's struggle to pay her bills. Even the mother's unpleasant new boyfriend is depicted sympathetically: his own background of abuse has contributed to his authoritarian approach to her children, whom he treats as if in need of a lesson to put them in their place—a physical one, if need be.

This soft touch to character is undercut by a somewhat programmatic approach to plot development. Expanded from a short story first published in One Story, the claustrophobic summer slowly builds to a head in a predictable, even exploitive fashion, and the pacing sags toward the end; the result is a novel that must have been more comfortable in shorter form. While the escaped prisoner who invades the town's gossip never makes an appearance, his presence influences Chris, who serves as a channel for the town wide unease. Headlines of the prison breakout dominate the imagination of the children, particularly since their father is a police officer expected to bring the man to justice. Hints are given of the escapee's grudge toward the father, and Chris is cast in such a light as to seem like the possible escapee himself. Certainly he is an unstable character, and his presence in the boys' lives becomes increasingly disturbing until he is revealed to be the worst kind of child predator. The dramatic climax revealing this falls flat, however, and worse, feels cheap and narratively convenient. It punctures the fog-like sense of unease and replaces its interesting, complicated mix of emotions with one lurid stroke that rings cheap. Instead of allowing the uncertainty of the divorce, the new boyfriend, and the looming poverty of the family to cast an appealing dimness over the novel, Chris's act makes all of these implicit threats concrete while simultaneously belittling real-world instances of child abuse by implementing it as a cheap, late-breaking plot device.

Nevertheless Smith has a cinematic verve in his writing, and while the plot feels recognizable and eventually takes a turn into the tawdry, it is also always easy to visualize, with several strong family relationship scenes. Smith mostly manages to steer clear of the overly self-conscious precociousness that sometimes attends child narrators, and his quiet depiction of a family falling apart has an honesty that can be devastating. It is only too bad that he saw fit to add the unnecessary ‘dramatic' touch of the older brother's rape and abduction, which disturbs the delicate tone of the novel to no good purpose.

Cote Smith grew up in Leavenworth, Kansas, and various army bases around the country. He earned his MFA from the University of Kansas. His work has been featured in One Story and FiveChapters. Smith lives in Lawrence, Kansas.