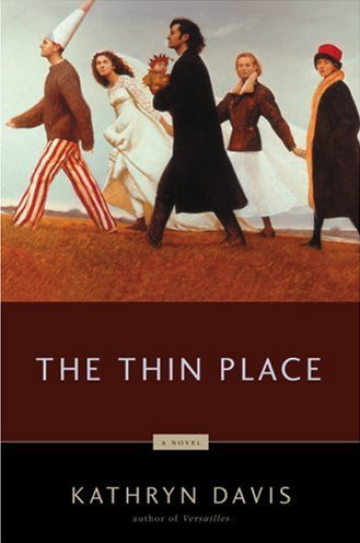

Kathryn Davis's THE THIN PLACE

In The Thin Place, Kathryn Davis creates another world, a semblance similar to the one we inhabit, yet composed of different primordial ether. Davis details the events of one season in a conjured New England town. And conjured it is, for seemingly ordinary Varennes is a surreal landscape in which the worlds of mortals and immortals intertwine. Nothing is what it seems - tragedies seem to repeat themselves as if ghosts were enacting rituals. Twelve-year-old girls are petty, stubby, sexual, and precocious priestesses, while men are resurrected, and insane women who sing mellifluously in the church choir and aging women in the Crockett's home converse with wisps. An archaeologist's wife is continuously unfaithful, but he doesn't mind since it affords him the liberty of living alone in a tent in the Arctic. Cats, dogs and insects love and introspect. There are no heroes or heroines - every character is given equal significance.

The inspiration for her sixth novel, Davis notes, came from her visit to a convent outside of Peekskill, overlooking the Hudson River. As one of the sisters lay dying, the bells of church poised to ring in ritual, she miraculously recovered. When Davis enquired how such a thing was possible, another sister told her that this was a thin place, where the membrane between this world and the spirit world was very thin - anything could happen. Similarly, in Varennes, time ceases to exist in sequential form. Time treads so heavily that it leaves impressions in this thin place.

The story lacks progression - if one were to revisit Varennes - the same spirits would roam and exude their thoughts, as if in purgatory. There is no buildup - and when the inevitable climax occurs, one is caught aware and unaware simultaneously. Temporal things do not seem to matter - there are timeless spiritual battles to be had. The book is unconcerned with plot or with actions, but with what thoughts and what feelings had a hand in commanding muscle to move and wreak action.

Stylistically, The Thin Place, is reminiscent of descriptions present in Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway and Faulkner's As I Lay Dying. In introspections, Davis uses repeating monosyllabic words to signify important moods and obsessions in the stream-of-consciousness narrative. Like Mrs. Dalloway, the book rapidly shifts from one character's perspective to another. Yet what The Thin Place is most similar to is not so much another book, but a work of mixed-media assemblage art. The Thin Place is composed of juxtapositions of police reports, diary entries, church service programs, horoscopes, private thoughts of humans, animals, insects, God, nature - consciousness streams unbounded. All this leads to a sense of privilege but also to a sense of confusion, which blends the characters - especially those of Helen and Billie, Piet Ziebrugge's mother and love interest. Their lives and thoughts are so intertwined that people seem indistinct, their membranes are so permeable, and their thoughts fill their environment as if they were skinless, boundless beings.

Given the profuseness of thoughts, it is unexpected that Davis's treatment of the characters is so entirely unsentimental - it is nearly pitiless. Not only does she stay entirely unbiased towards good and evil - everyone is given equal standing, despite what the reader may perceive as inherent emphasis. No one is entirely likable, nor are they lovable. Even the few characters for whom she has distaste, like mother and daughter Kathryn and Sunny Crockett, are given a chance to express their thoughts, albeit limited airtime. To Davis, Kathy and Sunny Crockett represent the true evil in this world - a world that seeks to benefit itself at the expense of others and nature; a world that is soulless and spiritless and does not desire redemption.

Characters that we come to care about are reduced to lesser fates and non-existences, and unapologetically so - as a statement of fact. Perhaps Davis' view of the natural world is that it is indifferent and cruelly nonchalant. It is then unsurprising that the biggest role is played by Davis - she is a resolutely unsentimental prophet for her Varennes. I could not help but wonder if all of these characters were representations of the author herself - because more than a work of fiction, I found the book to be a philosophical text, a powerful introspection of the author's mind, reminiscent of Agnes Varda's 'Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse,' (The Gleaners and I) where the subject matter is supposedly about gleaners of all varieties in France, but it actually provides the backdrop on which Varda casts her anxieties, observations and senses of goodness and evil.

Davis is a demanding author who assumes a certain sapience from her readers. She refers to Julian of Norwich1 with nary a description, numerous references to the bible, and books that must have been read. More demanding than whether or not one is well and widely read, Davis forces one to retreat into and retrace one's thoughts. The Thin Place is a self-conscious (self-aware) read and deserves a careful reading, in a quiet place where one can introspect. So much introspection, so many voices, so much drowning in sounds and thoughts.

1Julian or Juliana of Norwich (c. 1342 - 1416) - considered the greatest of the English mystics. Her 'Revelations of Divine Love' explores the great love of God for men and the detestable character of human sin.