Mykel Board's EVEN A DAUGHTER IS BETTER THAN NOTHING

Mykel Board's Even A Daughter Is Better Than Nothing lacks the type of overt soul-searching and self-discovery that one might expect from a travel book, much less one in which the author travels to Outer Mongolia, "a place as distant and foreboding as the moon." Although Board, best known for his column in Maximum Rock n' Roll does indeed find out some things about himself, he is not interested in philosophizing or grand cultural statements. Rather, he is mostly interested in sex, booze, and experiencing Mongolia to the fullest, which means involving himself in all the intricacies of the culture (even the more unseemly ones). The result is an unusual, entertaining, and refreshingly low-brow, portrait of Mongolia.

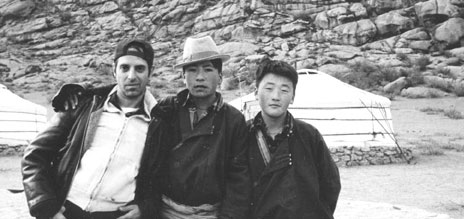

When we first meet our narrator, it is 1995. Mykel has just acquired a master's in linguistics, toured in the punk rock band "Artless" and has offended many with his column "You're Wrong" which he writes for a San Francisco magazine. ("Conservatives call me liberal. Liberals call me reactionary.") One night, while scanning for information about bisexuality in Polynesia, the bisexual Mykel discovers a group called soc.culture.mongolia and his adventure begins. After assuring various people that he is not a Christian interested in converting Mongols but "a jew who is not interested in converting anyone," he befriends a professor in Maryland who manages to get him a job teaching English at one of the most prestigious universities in Ulaanbatarr. A year later (things, we quickly learn, move at a snail's pace in Mongolia), he is on his way, despite warnings. "Mykel," [the professor tells him], "Mongolia is tough. Since 1990 people haven't had enough food to eat. For the first time in their lives, they have no jobs. They drink. And drink. Roaming bands of drunken, angry, unemployed thugs mug people at random."

Indeed, we soon learn, Mongolia is tough. The plumbing doesn't work, the electricity doesn't work, no one shows up when they are supposed to, and the icy winter lasts from September through June. But Mykel quickly learns, the Mongols also like to drink. Much of Mykel's stay in Mongolia is lost in a haze of vodka shots. The often drunk Mykel even ventures to the discotheque (like any average American in a foreign country) in hopes of getting laid. Occasionally, he even finds success despite an aversion to showering.

Indeed, we soon learn, Mongolia is tough. The plumbing doesn't work, the electricity doesn't work, no one shows up when they are supposed to, and the icy winter lasts from September through June. But Mykel quickly learns, the Mongols also like to drink. Much of Mykel's stay in Mongolia is lost in a haze of vodka shots. The often drunk Mykel even ventures to the discotheque (like any average American in a foreign country) in hopes of getting laid. Occasionally, he even finds success despite an aversion to showering.

The Mongols (almost endearingly) also like to try to beg and con Mykel and his friends out of money. When, for the hundredth time during Mykel's journey, he and a fellow teacher hear the familiar words -- "I only a poor Mongolia...I so low. You American. You English. You so high" -- his friend begins strumming a fake violin. And yet, when the same Mongolian friend later informs them after they claim they don't have much money to give, "You a special kind of tourist...you like to do things cheap. But you still a tourist...you work here, but you leave. You can't be part. You see things like tourists. You look and then you leave," Mykel and his friend know that he is right. As much as he feels a part of Mongolia at the end of his say, Mykel makes it clear that he knows his limits in this country.

After witnessing a sheep killing ritual, a wrestling competition, a near death experience in the Gobi desert, and Hurd, the only ROCK band in Mongolia, Mykel falls in love with Mongolia and its amazing people. "This is the madness I'll miss. This is the unpredictable frustration and illogical that I've come to love in Mongolia..." he thinks as he pulls out his nine dollars to pay for eight dollars worth of Mongolian tugriks. Mongolia, in Mykel's eyes, is an absurd carnival come to life. The America he returns to, in comparison, is "a sterile, increasingly ordinary place." When Mykel returns to New York, "the former Lower East Side drug and punk scumpit is now filled with expensive restaurants and sushi bars...a mother pushes a stroller in front of her, gazing down at the curly-haired blonde angel..." and it makes him "want to retch."

At one point in the book, Mykel is advised to only eat from street vendors who are popular. If no one is buying from them, it means their food is rotten and will cause food poisoning. Immediately after being told this, Mykel searches out the grubbiest and most unpopular vendor. As can be expected, he becomes violently ill. What might look like stupidity is really a hedonistic and almost religious quest for experience. And in the end, this is what is key about the book. Mykel wants to try everything - good or bad. The more ridiculous the situation, the more prone he is to go out and grab it. After all, this is a person whose entire trip to Mongolia is based on the idea that is "is the furthest away you can go."

And although his mission is in some ways adolescent and naive, it is also endearing. Our narrator is an idiot, a punk, and a Gen Xer, on a quest to find an experience untainted by "Staples, McDonald's, and Barnes & Noble." In the end, with Mongolia, he seems to have found it.