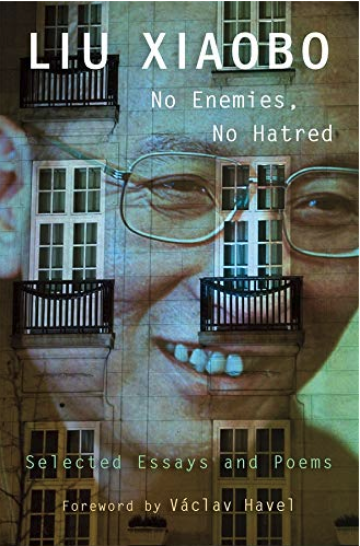

NO ENEMIES, NO HATRED by Liu Xiaobo

Almost two years have passed since Liu Xiaobo, the poet, professor and political dissident, won the Nobel Peace Prize (becoming the first person from mainland China to receive the distinction). However, Beijing was not pleased by Liu's award, as he is currently serving an eleven-year prison sentence for “incitement of subversion.” Ironically, that bogus charge is a twisted sort of honor unto itself.

Far from a criminal, Liu is the foremost advocate of human rights and political freedom in China today. And his writing is subversive inasmuch as it is revolutionary. With amazing courage, Liu speaks truth to power by demanding that the Communist Party respect what he calls “human dignity.” Unlike many contemporary Chinese writers, Liu refuses to censor himself or to turn away from controversial subjects. And for his audacity and outspokenness, the authorities awarded him with his third and longest stint in prison. Since the Award Ceremony in Oslo on 10 December 2010—which neither Liu nor his family were able to attend—Liu Xiaobo's name and his story have become more well-known in the West. Yet Liu's poetry and prose remain relatively unknown, in spite of the fact that he has published hundreds of essays and seventeen book-length collections. Part of the problem is that much of Liu's work has not been translated into English.

Fortunately, an impressive new collection entitled No Enemies, No Hatred: Selected Essays and Poems (Belknap Harvard) gives the anglophone reader a chance to sample some of Liu's best writing. And the collection is unlikely to disappoint. Liu's prose style is simultaneously clear and poetic. He has a knack for making eloquent proclamations.

“In transitions toward liberal democracy,” Liu writes, “the splendor and strengths of nonviolent resistance are plain to observe: although people must still deal with tyranny and the suffering that it causes, they can respond to hate with love, to prejudice with tolerance, to arrogance with humility, to degradation with dignity, and to violence with reason.”

At the center of all his work is this commitment to nonviolence, human dignity and the moral imperative to speak one's mind—regardless of the consequences. Certainly, Liu has earned himself a place among the likes of Václav Havel (who provides the foreword to No Enemies, No Hatred) as one of the great literary dissidents of modern times.

While reading No Enemies, No Hatred, the reader may breeze through Liu's poems and linger on his essays. This seems to be the fate of many writer-dissidents; their literary contributions tend to be overshadowed by their political work. Take Havel, for instance: his essays and political career, not his plays, made him famous. However, it would be a mistake to overlook Liu's poetry, for they are the best expression of Liu's eclectic mind.

Almost all the poems included in No Enemies, No Hatred were written while Liu was serving a three-year sentence in a labor camp in the nineties. Far from reeducating Liu, one must assume that the camp environment gave him the chance to contemplate many disparate (and sometimes forbidden) topics: massacre victims, Vincent Van Gogh, Immanuel Kant, St. Augustine and Jesus. And accompanying Liu through it all is his wife, Liu Xia, to whom he dedicates nearly all his poems. In this reviewer's mind, Liu's best lines are the ones written directly to Liu Xia, like these from a poem entitled “Your Lifelong Prisoner”:

My dear, I'll never give up the struggle for freedom from the oppressors' jail, but I'll be your willing prisoner for life.... Inside you I grope in the dark and use the wine you've drunk to write poems looking for you I plead like a deaf man begging for sound Let the dance of love intoxicate your body I always feel your lungs rise and fall when you smoke in an amazing rhythm you exhale my toxins I inhale fresh air to nourish my soul

It is a shame to think that such a soul is currently behind bars. Unfortunately, Liu's situation appears unlikely to change. In October the Communist Party will undergo its largest leadership change in ten years. Moreover, President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Wen Jiabao will relinquish their respective titles for the first time in twenty years. During this time of transition, the Chinese leadership probably will not do anything to rock the boat. It is some consolation to know that his work is being read. And hopefully one day it will be read in China too.

Liu Xiaobo, winner of the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize, is a Chinese writer and human rights activist.