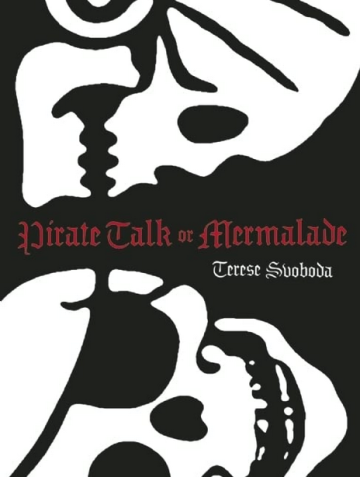

Pirate Talk

"Pirates are a perfect picture of a person piecemeal, falling apart,” a character pronounces near the end of Terese Svoboda's Pirate Talk or Mermalade. Given the novel that precedes this statement, it's hard to deny its truth. In Pirate Talk, pirates (and those who fraternize with them) are highly unstable, constantly going to pieces and reassembling themselves into new and unexpected configurations. Bodies are especially mutable: characters lose limbs, switch genders, and even reveal themselves to be not quite human. Yet despite the blood, bone, and gouged-out eyes of this novel – or maybe because of them – there's a frantic comic sensibility at work, a Looney Tunes-like glee in the characters' dizzy confusion or states of gory flux.

Pirate Talk tells the story of two unnamed siblings and their disastrous careers on land and sea. The older of the two dreams of earning a fortune repairing watches and carving whalebone scrimshaws, which he gives elegant, overlong titles; of one, called “Man Sawing a Tree on the Occasion of His Betrothing,” his sibling comments, “The title is bigger than the piece.” A landlubber at heart – “The ocean's too much a cradle for a man so grown as myself,” he boasts – he prefers even working the docks to the sea's fickle bounties and dangers.

Yet chance conspires against him: fleeing a failed marriage on a ship called Hope, he's the victim of two pirate attacks and a shipwreck. In rapid succession, he loses his leg, eye, and hand – leaving him peg-legged, eye-patched, and hook-handed. To add insult to injury, a parrot repeatedly torments him, perching on his shoulder to shriek a single word that speaks to his hated outlaw condition: “Hanged.” “You shan't pass for naught but pirate,” his sibling observes. In the process of falling apart, piece by piece, this character becomes the embodiment of everything that, on the inside, he never wanted to be.

His sibling, five years his junior, has a similar problem with false appearances. Raised as a boy and “light of beard” even in adulthood, this character has an unusual secret: he – or perhaps I should say she – is in fact a woman, raised by her mother to conceal her sex to protect herself from “men who would open me up.” She lives as a man successfully, enlisting on a pirate ship and holding her own amid the often-grisly chaos: she even amputates her brother's leg. But there are times when she drops the disguise. When she's rescued from a desert island, she poses in what her brother (and the reader) thinks is drag, as an innocent female castaway from the Mayflower, and we find she can shed gender roles as abruptly as her brother can lose limbs. Her sudden femininity is so convincing that the predatory French sea captain even demands her sexual favors.

We later learn that she bears his child in secret, then casts it from the decks to the lair of the merpeople below.And speaking of merpeople, it's not called Mermalade for nothing. The third player here at first appears to be a woman; when we meet her, she's employed as a governess and hobbles about on a cane, reveling in the glories of the printed word – “Reading is like a sea voyage, you either attend to it and see the world, or you stay at home” – and the flora and fauna of the land. Yet when we encounter her next, hooked at the end of a fishing line, she is much changed: “This fishy part is new and shocking,” comments the sister, observing her former friend's tail, to which the mermaid replies rather sassily, “Not so new. The skirts all women wear to confound men hid it.” The mermaid has another surprise in store as well: according to her, the younger sibling is not only female, but half-mermaid, her sister from another mother.

Since the novel is told entirely through the character's voices, without even dialogue tags or names to distinguish the speakers, we are never given even a single line of objective physical description. Although this at times makes the reading experience confusing, especially in scenes with more than two speakers, it has a curiously appropriate effect: since we see the characters only as they are perceived by others, we have no fixed idea of them, no access to their internal lives or “real” selves. We know only what they choose to tell each other. And this makes the characters' rapid transformations possible, plausible, on the page. When the mermaid reveals her tail, or the younger sibling makes reference, for the first time, to her “female parts,” we don't feel as though the author has tricked us with misleading details or wrong pronouns; when the brother screams, “My eye!” we don't have to picture his grisly disfigurement. Instead, we're able to continue sailing along, buoyant on the surface of the text.

As rollicking a voyage as this is, at times I did want something deeper. When the mermaid first tries to convince the younger sibling that they are sisters, she tries to drag her into the sea. The younger sibling protests, “The water is fearsome, the ocean is death. I am alike in this with my brother—we do not enter the water.” And neither does this novel. Although the book showcases corpses galore – a dead whale, hanged men, the siblings' mother after her suicide, and several victims of cannibalism, to name a few – and highlights its characters' corporeality through the mutilations and anatomical “reveals” described above, we never feel the threat, the risk, that the body's impermanence ultimately imposes. Keeping the characters as disembodied voices allows Svoboda to make imaginative leaps, to subvert the reader's expectations with a single line; but it also makes it difficult for her to create the kind of intimacy with them that would make us react emotionally to their plight in the final pages, when the book's tone seems to take a sudden turn toward pathos. Still, the book is hilarious and vivid from beginning to end, and that makes it treasure enough for me.

Terese Svoboda is the author of the poetry collection Weapons Grade, the memoir Black Glasses Like Clark Kent, and the story collection Trailer Girl. Her website is http:s//www.teresesvoboda.com.

Terese Svoboda is the author of the poetry collection Weapons Grade, the memoir Black Glasses Like Clark Kent, and the story collection Trailer Girl. Her website is http:s//www.teresesvoboda.com.

Chandler Klang Smith's genre-bending novel The Sky Is Yours (Hogarth/Penguin RH, 2018) was listed as a best book of 2018 by The Wall Street Journal, New York Public Library, Locus, LitHub, Mental Floss, and NPR, which described it as "a wickedly satirical synthesis that underlines just how fractured our own realities can be during periods of fear, unrest, inequality and instability." Chandler has an MFA in creative writing from Columbia University. She has served twice as a juror for the Shirley Jackson Awards, worked in book publishing and as a ghostwriter, and currently teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College.

Chandler Klang Smith's genre-bending novel The Sky Is Yours (Hogarth/Penguin RH, 2018) was listed as a best book of 2018 by The Wall Street Journal, New York Public Library, Locus, LitHub, Mental Floss, and NPR, which described it as "a wickedly satirical synthesis that underlines just how fractured our own realities can be during periods of fear, unrest, inequality and instability." Chandler has an MFA in creative writing from Columbia University. She has served twice as a juror for the Shirley Jackson Awards, worked in book publishing and as a ghostwriter, and currently teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College.