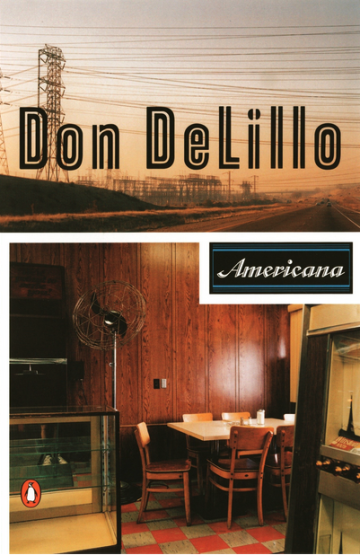

Revisits: Don DeLillo's AMERICANA

There is blood on the hands of the American soul. If we are born American citizens, we inherit this stain; but if we begin our lives elsewhere and then choose our American citizenship, we must absorb the stain as a necessary burden. We must prove or disprove through work, destruction, or enlightenment—through choice and action—that, to a point, we are well-suited to our national identity. Perhaps the debut novels of American authors are the records of these choices. Don DeLillo's Americana is a confessed exemplification: “It's no accident that my first novel was called Americana. This was a private declaration of independence, a statement of my intention to use the whole picture, the whole culture.”

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “Americana” this way: “things produced in the U.S. and thought to be typical of the U.S. or its culture.” Many such things, the composite of which creates a familiarly complex and self-contradictory identity, appear over the course of DeLillo's novel and manifest in the protagonist-narrator David Bell. Bell is a young and handsome television exec living and working in New York during the 1960s. He is educated, from a privileged background; he seduces most women that he meets in instances that he refers to as “ego moments.” He has an ex-wife whom he loved at one time, but he allowed the relationship to fall apart. Within his television company he is in a position of moderate power, yet he spends most of his time paranoid or flippant about office politics. In one of the novel's first scenes, Bell is at a party and decides to spit on ice cubes in the freezer before putting them back. Just because he can. It is David Bell's twenty-something inclination toward cynicism that stands in his way, as the nation's cynicism and materialism stand in its way: “I had almost the same kind of relationship with my mirror that many of my contemporaries had with their analysts. When I began to wonder who I was, I took the simple step of lathering my face and shaving. It all became so clear, so wonderful. I was blue-eyed David Bell. Obviously my life depended on this fact.” Bell undermines his own potential for greatness by assuming that The Image trumps all. Perhaps in America, especially during the second half of the Twentieth Century, when television and cinema avalanched their cultural power, The Image did. Perhaps it still does. It was the Vietnam War, which raged through the 1960s and 1970s, that permeated American homes with its consistent television news coverage: “The war was on television every night but we all went to the movies. Soon most of the movies began to look alike and we went into dim rooms and turned on or off, or watched others turn on or off, or burned joss sticks and listened to tapes of near silence.”

The book's first part is concerned with capturing the essence of Bell's ludicrous existence amidst corporate America and everyday office life; the second is concerned with American life at large and the power of film to craft what that entails. Confusion perpetually colors Bell's psyche, but his vaguely detached, semi-calculating intellect numbly categorizes and makes sense of the activity around him. DeLillo uses concise and definite sentences to maintain this ironically charged tone—and the conversations in the novel's first half manage to convey the experimental wackiness accompanying the time period's growing modern self-awareness, its desperate need to make sense of the revolutionary Peace-and-Love ideology juxtaposed with extreme and escalating violence. As a twenty-eight-year-old divorcee mostly removed from his parents' life (David's father is as removed from his son and his present reality as the “Plastics” dad in The Graduate), David is seeking direction. In the book's second half, we see him take to the open road, a literary trope that became increasingly popularized after Kerouac. The road meant freedom, possibility, the yet-to-be—it meant getting in touch with one's land and one's self. By seeking the American character in its fullness away from the global island of Manhattan, Bell hopes to discover his own character in its fullness. To do this, Bell brings along his movie camera under the pretense of filming a documentary on Navajos for his television company. This movie of Bell's soon turns into a self-reflexive restaging of his own biography in a hazy, near-hallucinatory mingling of past and present. He is obsessed with his own past, not overly remarkable or tragic, perhaps because this is usually the route one is supposed to take when trying to understand or connect with oneself. It is The Image of self-discovery.

Don DeLillo first began publishing novels in the 1970s, a decade of infamous lost innocence. Paranoia and the gradual realization of institutional corruption from the Watergate Scandal forward influenced American personages: characters in 1970s cinema like Jack Nicholson's Bobby Dupea in Bob Rafelson's Five Easy Pieces (1970) bore a penchant for self-destruction and societal mistrust. Once it was clear that the 1960s Counterculture would not overtake the mainstream (though it certainly made a beautiful impact), Americans were led to ask the essential question of themselves: how American am I going to be? David Bell, who begins the novel as a numbed-out, over-educated, under-spiritualized thrill-seeker with a normal-ish past he's trying to sort out, attempts to answer this question. Perhaps the goal of any coming-of-ager is to recognize the power in one's own individual freedom influenced by but ultimately apart from one's own country and the limitless potential that resides in its achievement. Though a person inherits the sins of the familial and national pasts that have come before him, and though he must attempt to make peace with his own personal past, the future urges us on with its promise of open territory. New and unmarked lands seem to await. ‘Americana' too represents a national ideal—an ideal we get further and further away from even as its hold on us tightens.

Donald Richard "Don" DeLillo (born November 20, 1936) is an American novelist, playwright and essayist. His works have covered subjects as diverse as television, nuclear war, sports, the complexities of language, performance art, the Cold War, mathematics, the advent of the digital age, politics, economics, and global terrorism. DeLillo has twice been a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction finalist (for Mao II in 1992 and for Underworld in 1998[1]), won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Mao II in 1992 (receiving a further PEN/Faulkner Award nomination for The Angel Esmeralda in 2012), was granted the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction in 2010, and won the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction in 2013.

Jude Warne earned her MA degree in 2015 from NYU's Draper Program of Humanities and Social Thought. Her Master's Thesis, "Let the Broken Hearts Stand", focused on American characters dealing with disappointment in the works of Bruce Springsteen and Sherwood Anderson. Jude earned her BA in Cinema Studies and Art History from NYU in 2011. She has written numerous reviews for Senses of Cinema, Film Matters, Journal of Popular Music & Society and Scope. She is also the music columnist at Red Paint Hill, an In-the-Field correspondent at Film International, a jazz critic at CMUSE and a contributing writer at Live for Live Music and The Vinyl District.

Jude Warne earned her MA degree in 2015 from NYU's Draper Program of Humanities and Social Thought. Her Master's Thesis, "Let the Broken Hearts Stand", focused on American characters dealing with disappointment in the works of Bruce Springsteen and Sherwood Anderson. Jude earned her BA in Cinema Studies and Art History from NYU in 2011. She has written numerous reviews for Senses of Cinema, Film Matters, Journal of Popular Music & Society and Scope. She is also the music columnist at Red Paint Hill, an In-the-Field correspondent at Film International, a jazz critic at CMUSE and a contributing writer at Live for Live Music and The Vinyl District.