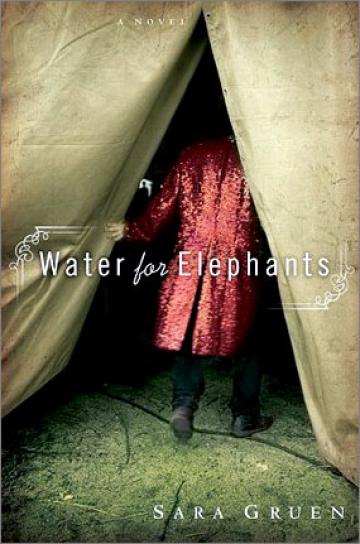

Sara Gruen's WATER FOR ELEPHANTS

In a pulp exposé occupying a realm somewhere between soap opera and History Channel mini-series, Sara Gruen neatly packages a cavalcade of spectacle-Americana into a commercially viable romance. Water for Elephants is a portrait of "The Benzini Brothers' Most Spectacular Show on Earth" - a fictitious 1930s circus tour as remembered by Jacob Jankowski, a nonagenarian sequestered in an assisted-living facility. From his saltless, butterless world of Jell-O molds and chaperoned bathroom jaunts, Jacob relives the crux of his youth as a circus veterinarian. His flashbacks provide a page-turning construction, and surface sketches of Depression-era mores.

The memory episodes begin just before final exams at Cornell University veterinary school: twenty-three-year-old Jacob receives news that his parents are dead, and in a miasma of grief, he flees the classroom and blindly jumps aboard a passing circus train. He literally dives head first into a world of rubes and rogues - a hierarchy of chaos in which he must stay on his toes just to keep his hide.

Within days, Jacob finds himself bunking with a midget clown and his terrier, guarding a gregarious floozy with acrobatic breasts, and sticking his arm into the jaws of a toothless lion. More ominously, Jacob finds himself falling in love with his boss's wife Marlena - a sequin-encrusted equestrian starlet - and feeling something very similar to love for the show's new elephant, Rosie. Predictably, the situation then spirals into a dangerous love conundrum. Marlena's husband possesses a sadistic side, which puts both wife and elephant in peril. Jacob, then, must tread the line between biting his tongue or being hurled from a moving boxcar.

The merit of Water for Elephants undoubtedly resides in the comprehensive scope of Gruen's research. Impetus for the novel was fostered by the author's captivation with the work of circus photographer, Edward J. Kelty, then fueled by months of research and trips to Ringling Circus museum and Circus World in Baraboo, Wisconsin. The resulting text teems with historical anecdotes of freaks and feats, reminiscent of the Guinness Book of World Records. Tactically placed archival photographs of bearded ladies and the like add a haunting shimmer of authenticity to the tales, resulting in the successful illumination of the unique rapture of spectacle that is so precious to Gruen and so elemental to the circus.

But historical elucidation stops there. Though at first the bizarre scenes and characters suggest a depth akin to a John Irving cast, they do not breathe beyond their data. This is due to conformist prose, and the formulaic plot of escape fiction. In fact, only when Gruen moves away from her fact-file of oddities and into her depiction of the mundane - the narrator's geriatric reality - does any investigation occur. Poignancy manifests in Jacob's rumination of life in the old-folk's home, and the rest, like the circus, is mere diversion.