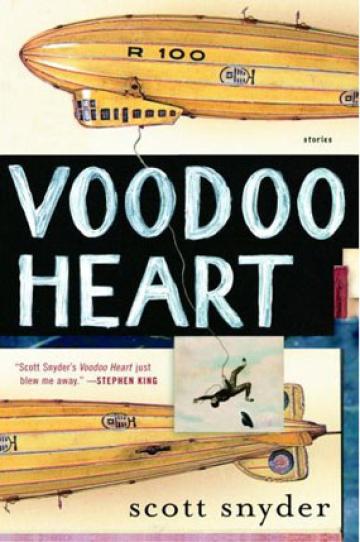

Scott Snyder's VOODOO HEART

Scott Snyder's new story collection, Voodoo Heart, is an ensemble that trumpets the arrival of an inspired and imaginative young American writer. The book, Snyder's first, is comprised of seven independent pieces-the majority of which have enjoyed previous literary life in prestigious journals such as Zoetrope: All Story; One-Story; Epoch; and Tin House. Under one spine, however, these stories meld together seamlessly, like a fantastic Tapas meal where each new arriving dish brings fresh sensation to the taste buds, but at the end the feeling inside the stomach is one of integrated contentment.

What's most striking about Voodoo Heart is Snyder's dogged ability to stay on point, relentlessly so, when dissecting the conscious and subconscious emotions and motivations of the male characters who dominate his pieces. Utilizing two primary backdrops of time-early 20th century and early 21st century-and a series of American backward towns and strip-mall depleted suburbs, each sharing the sweet simplicity of being cast aside and forgotten, Snyder proceeds to bombard these men with such a diverse and unexpected array of soul-stripping stimuli that one nearly wants to leap into the pages and offer up safe shelter. In About Face, for instance, the third story of the collection, we meet Miles Fergus, who, at the age of 29, must deal with the effects of a childhood accident where a bullet shot from a marathon-starter's gun fell to earth atop his head, nearly splitting open his skull and causing a hole inside his septum which results in a melodic whistle now and then. "Can you hear it yourself?" Williams asked, still peering up into my nose. "It's like tooot. Toooot."

Miles is also a humiliated by a failed attempt at heroics. After pummeling a man he has mistaken for a bandit stabbing an old lady in the ear, he discovers the bandit is her son, just testing her hearing aid. And, the clincher, is the woman Miles loves, the kidney-failing adult daughter of a Sergeant at the Juvenile Boot Camp he works as part-time trumpeter (revelry), part-time chauffer. The wan beauty, whom he ferries once a week to a far-away hospital to have her blood cleaned by a dialysis machine, chooses one of the camp's most insidious inmates over him to be her boyfriend. But all the torment has a purpose, as at the end of the tale we accept the idea, even welcome the fact, that Miles can be fulfilled in a diminished role, peacefully laconic, toiling at a unfrequented museum, giving information to bored schoolchildren, and playing mournful trumpet at the end of the day to an exhibit of a prehistoric man, whose evolutionary choice of a powerful chewing jaw over a developed brain doomed him and his hyper-masticating brethren to extinction. Perhaps Snyder's message in Voodoo Heart is akin: that greatness in life does not come from one being great, but rather in one accepting they are not great. Simply, Snyder reveals his characters' flaws in such a way that these flaws, in the end, are their strengths.

Snyder has the good timing and strength of craft to tether the most surreal moments in his stories to the most tangible. He accomplishes this through his gritty but poetic style of describing place, revealing a desperate but beautiful American landscape. He writes, "In the winter the ice is so thick it glows blue. You can hear it slowing rolling forward at night, splitting and pushing on, making noises like grinding teeth," in Wreck. This landscape acts more like a willing participant than silent partner. For example, somehow, in Blue Yodel, it makes sense that Pres would be hired to sit near the tip of Niagara Falls helping to fish would be jumpers-floating by inside barrels-out of the churning water. As it's perfectly natural for Pres, at the end of the story, to swing suspended in the air, floating in the clouds over the arid and crusted Arizona earth, clinging to a rope attached to a zeppelin carrying his wayward girlfriend inside.

Snyder, I believe, has helped to redefine the American pastoral novel with Voodoo Heart. Like Fenimore Cooper long before him, he has shown an ability to use the American landscape-be it paved in cement or sprinkled with pine needles-as a means to shed light on our society. And like Cooper, his writing is crisp and clean but poignant and meaningful. And they stay with you, even if it hurts. Like the country song his character Max in Dumpster Tuesday describes, a song about two love-starved truckers (a man and woman) who can never seem to meet, only converse by CB. "...the woman eats at a truck stop, and the man comes in so soon after her that when he unknowingly sits down on her stool, her tip money is still on the counter. The change is still warm from her pocket."

Snyder's stories are still warm in my pocket. I'm sure they'll be there for a long while.