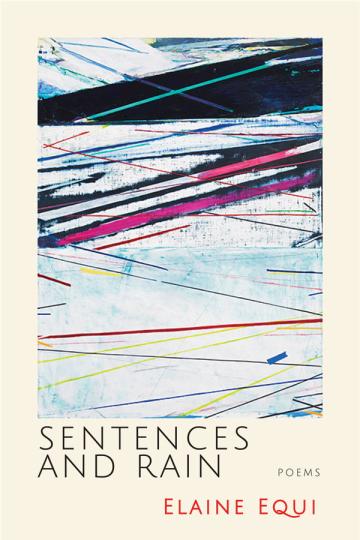

SENTENCES AND RAIN by Elaine Equi

On every page of Sentences and Rain (Coffee House Press), Elaine Equi's latest collection of poetry, you will find words and images in surprising, purepoetic, and truth-revealing juxtaposition—pages thrumming with the activity of an original imagination. As Equi writes in the titular poem: the words “drench us all at once,” with their “bend/and reach/toward meaning.” They drench with cleverness and poise, but never inundate; they reach toward but never clutch at meaning. Her poems, “resist the intelligence/Almost successfully,” as Wallace Steven once exhorted—they thrive on a knife's edge of sense and imagination, intellect and form.

Yet—and this is by strict design—there is always room to breathe in an Equi poem: “gaps/let the work/breathe//let the reader/in among.” If a poem's words are its lifeblood, then its spaces are its lungs—Equi's poems breathe in and expel clean airs. Take these opening lines from “If I Have Just one Word”:

Well, still that's a lot of possibility. A word can be a shriek or a chrysanthemum— Barbed or honeyed—

There is a lot going on here. The humble enjambment in the first couplet leads us into the second line's grand idea of ‘possibility,' which, at the break, we are allowed to savor. What is the possibility in just one word? Out of this big intellectual space the next line's “shriek” hollers out jarringly a shrill note—“chrysanthemum” following resolves the note into a muted beauty. The hard regular iambs of the first line melt into the softer iambs of “chrysanthemum”—and then we breathe again. The movement from high-to-low, loud-to-soft, settles, and we are “in among.” One finds these hyper-pressurized beauties throughout, and too, poems made alive by these “breaths”: both are hallmarks of not just this collection, but her oeuvre.

Artworks and artists are often the subject of her poems, and the reader gets the sense Equi can let us “in among” her own work because she is a masterful inhabitor of others'. In “Time Traveler's Potlach,” a series of statements proposition gifts for an artist (for us, too). The gift, and this position of giving is wonderfully typical in her poetry, is her assiduous and joyful interpretation of the artist, their works. “For T.S. Eliot:,” she writes, she gives, “a crate of peaches with a note that reads: ‘I dare you.'” Of all the lines to take from the immortal “The Love Song of J. Alfred Pufrock,” “Do I dare to eat a peach?” is rarely the one extracted (disturbing the universe seems mightier)—but Equi keenly reads the congested exasperation in this line, that feeling's absurd release, how it so aptly stands in for the blocked-up poem and poet, and how refashioning and returning the image is itself deep engagement with Eliot, itself a balm for Mr. Prufrock—all while the peach lives within the conceit of the “Potlach,” the gift-giving meal. She takes these others—artists of any stripe, characters, ideas she likes—seriously and respectfully, and yet treats them with, yes, a juicy dose of panache and wit.

“Blue Jay Way” operates amidst the eponymous George Harrison tune (Equi is rangy, too). She begins by assigning the music images, like a poet-director, or really, a listener: “Like much great horror, it begins with fog. Fog and Organ music”—but by the end of the poem, after her song-film unfolds some (“we listen as if to a hypnotist, and our eyes grow weary”), she is meditating on physical space and her personal relationship to it: “so why not succumb now and then, if only for nostalgia's sake, to the lure of the lost?” This meandering coheres with concept of this song and poem in at least four ways: first, by tuning to the song's tone precisely (it's a creepy, meditative song); secondly, by acknowledging the historical facts of the song's composition—George Harrison writes it jet-lagged, waiting for friends to arrive at the LA home he is staying in (they are lost—he waits, composing); thirdly, by meandering like the dark winding hills of Hollywood themselves; and fourthly, explicitly: Equi tells us this is what she's doing. “We see ourselves from above—a bird's-eye view—driving the never-arriving car but also waiting back at the house,” she writes. With Equi as our guide, we find the secret spots of artworks—the spots belonging to the late-night listener, the avid reader. This is what she shares with us. She is our trusted, beloved local guide.

And all of Equi's poems feel like local tours through thoughts and sounds and sense, a trip made meaningful by sincere love for the destination, and the powerful attention paid to that love. In effect, she succumbs to the lure of losing her way in, well, the way. It's why she can write a poem as trim as “Trees Rehearsing”: “tomorrow's/soft-spoken//over today's/sharp edge” (end of poem) and still evoke something exquisite. Every poem of Equi's is a kind of ekphrasis, as it is not so much “ideas” Equi rigorously gets to, but their emergence from the acutely observed. Any moment of any day, any nuance of any sensation, can, infused with her sensibility, become something meaningful: every drop of rain, every sentence. The miracle of Equi's poems is that this isn't some artsy-fartsy put-on, but the source of her authenticity. The poems really feel this—they are this, and they are true.

Elaine Equi: Elaine Equi was born in Oak Park, Illinois, and raised in Chicago and its outlying suburbs. In 1988, she moved to New York City with her husband, poet Jerome Sala. Over the years, her witty, aphoristic, and innovative work has become nationally and internationally known. Her book Ripple Effect: New & Selected Poems was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and on the shortlist for Canada's prestigious Griffin Poetry Prize.

Among her other titles are Surface Tension, Decoy, Voice-Over, which won the San Francisco State University Poetry Award, The Cloud of Knowable Things, and Click and Clone. Widely published and anthologized, her work has appeared in the New Yorker, Poetry, the American Poetry Review, the Nation, and numerous volumes of The Best American Poetry. She teaches at New York University and in the MFA program at The New School.