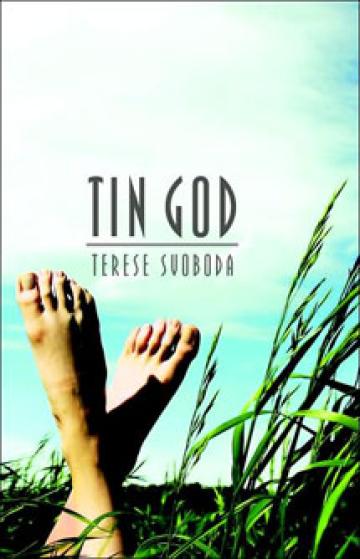

Terese Svoboda's TIN GOD

Imagine wading through a field of wild grass that extends over your head. Your ruined shoes squish through mud; vines grasp your ankles. Wind whispers voices you cannot understand. You came looking for something you deeply desired, but the farther you push into the tangle, the more you realize you only want to find a way out.

In Terese Svoboda's new novel Tin God, God narrates the story of two of Her subjects - a 16th century conquistador, and 400 years later, a male exotic dancer named 'Pork' - conducting desperate searches through the same plot of land. One seeks gold; the other, a lost bag of dope. A range of crafty characters aid or avert their efforts. More menacing forces - tornadoes, fire and people - threaten to burn and consume everyone and everything.

Like its characters, a Tin God reader might struggle, at the outset, with orientation. God's voices, like Her motives, shift with the wind. One moment She is omnipotent, then suddenly She's in over Her head with the mortals. Technically, this takes some getting used to; then the story accelerates. While Pork and the Spaniard dig through the stalks, something evil lurking nearby fiercely digs for them. It's a fast and thoroughly rewarding read - equal parts mysterious, theological, mythological, funny and suspenseful.

God twists us into the grass when She describes the Spaniard's terror of being left behind by his peers:

... he's been afraid of this ocean of grass, this rough-weather tsunami of grass that messes and fronts the wind to a boil...

And later, as Pork despairs in the over-cultivated field lain to waste by a tornado, God reminisces of the field before man stained it with crops and chemicals and machinery:

... when the grass grew up to here - over your head - with all the rows peripatetic, willed and wild and tall ... no, you couldn't see out anywhere, so tall and thick was the curtain.

Thick with praise for me.

Thick and tall because I said so.

There is poetic claustrophobia in the fields, automobile interiors and subterranean basements. Stunning moments come when characters spring from the clutter for a second: an Indian boy strung up above the fields on a pole in a cruel ritual; the thirst-crazed conquistador stumbling suddenly into the river; Pork watching a wind squall hit a lake. But these are fleeting moments; God quickly plunges them back into the thicket.

There is a dark possibility that binds these two stories - that God is really malevolent, and hardly forgiving. God doesn't want you to see above the grass. By searching for a way out, you trifle with God. And if you trifle with God, God's going to trifle with you.

Tin God's moments of rural desperation and pure visual honesty may remind the reader of work by Denis Johnson or, earlier, Breece D.J. Pancake. But Tin God is truly its own story, told in its own voice, and painted artfully into its own ornate, if overcrowded, landscape. You will find that you are rooting for the searchers, and with them, you are searching for the hidden truth. So, reader, take to the field - but proceed with care.