THE ANTIGONE POEMS. Poetry by Marie Slaight. Art by Terrence Tasker.

Though doomed from birth and dead by the exodus, Antigone endures endlessly. As the central figure in Sophocles' eponymous tragedy, she was conjured—righteous and rebellious—in 441 BCE and has been invoked, translated, reincarnated, and re-imagined countless times since. In modern history, she has spoken in rhymed meter and free verse; she's chatted casually and sung operatically. She's been painted, recorded, filmed, and pondered. To name very few, she has been rendered by Bertolt Brecht (for the stage in 1948), Pulitzer Prize winner Lynn Nottage, (who linked the tragedy with the Patriot Act) Seamus Heaney (who penned her a libretto), and, of course, Anne Carson, who gifted her with the line bingo in her 2012 translation. To throw your hat into the Antigone ring in 2014 is a bold move, an implicit assertion that your offering is unique enough to warrant its place and to contend with the giants that have come before it.

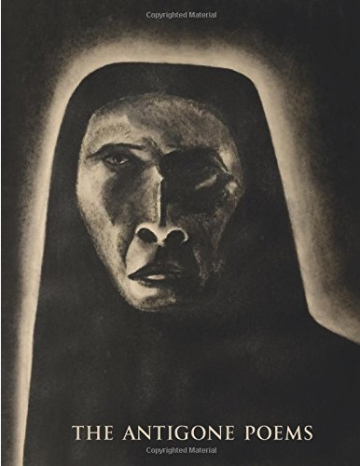

Enter The Antigone Poems, a slim volume of sparse verse written by Marie Slaight, interspersed with imposing charcoal drawings by the late Terrence Tasker. While only recently published, the book was created in the 1970s, while both poet and artist were living in Toronto and Montreal. Slaight currently lives and works in Sydney, Australia, where she established Altaire Productions & Publications, the company which published (or, arguably, self-published) the work. There does not appear to be any particular reason why the work was published only recently, though the book is dedicated to Tasker, who passed in 1992, at the age of 45. The forty-year delay and the artist's death does lend the book a sudden air of mystery—It's all part of a very well designed, intriguing package.

The Antigone Poems is split into five slender chapters and, in total, contains only 33 poems or textual fragments and six drawings. Every other page is blank, save for a header and a Roman page number. The distended layout and the luxurious cream paper, on which the text is printed, give the book a bulk and weightiness that is at odds with the minute slips of verse. A poem in its entirety:

Black blossom... Sweeps... Realm of desert ash.

On its own, at its best, the text recalls the fragments of Sappho. Here Sappho's Fragment 52, translated by Anne Carson: I would not think to touch the sky with two arms. Here's Slaight: ...gods speak to the wind and winds whip through me... Slaight's lean verse is populated too with a vocabulary that recalls antiquity: daemon, gods, earth, whip, wilds, and flesh all make numerous appearances.

While one might argue that Slaight's text borders on mimicry, she smartly positions the book as a work of oppositions, raising it above the role of imitation and imbuing it with a sort of savvy power. She understands that while the words she has chosen may appear to be morsels, they are as filling as meals. By keeping the text deliberately spare, surrounded by empty space, she navigates away from the realm in which talk of daemons is trite or cheesy. This play on oppositions bears out further in the back-and-forth between the text and illustrations. Tasker's charcoal sketches, appearing solo at the end of each chapter, feature dark faces wearing stern expressions. They recall Greek masks of tragedy, albeit angrier. While not beautiful or engrossing, the severe masculinity of the facial features and dominating dark tones provide a much-needed sense of weight and grandeur against the slight text.

As a reader, it's not necessary to have a clear knowledge of the original tragedy, but it does help to inform and interpret the work. Out of context, the moody vocabulary, erotic references, and intense images might seem juvenile. What you should know, in brief:

There was a ruler named Oedipus who unwittingly murdered his father and married his mother, who gave birth to four children/siblings, Antigone included. After much deadly drama, the morally astute Antigone defies a cruel royal decree, an act for which she is sentenced to death. She hangs herself and, in a chain reaction, other people stab themselves. There is regret. There is anguish. There is, as Slaight says:

No words. Only the gaping, silent scream. Go inside... Until one word Is blood. Until then... Silence.

Unlike the Theban play, Slaight's poems veer in and out of first-person perspective, though it is never explicitly clear who is speaking. Intensely personal observations take the place of the perpetually at-arm's-length Greek chorus and turn character's verbal outcries into interior monologues. This decision suits the tragedy's inherent passion and lends an inspired intimacy to the ancient work:

I remember only the rage... Screaming... My head breaking... Wanting to kill... You are a murderer... Then nothing. Silence and decline... And a veil of gray descending.

Ultimately, this muddling of the narrative identity, the essential lack of concrete acts, and the severe fragmentation of the text results in an overall vagueness that turns The Antigone Poems into more of an atmospheric piece than anything else. It is not truly a translation or a retelling so much as an essence. Reading Slaight's work alongside a modern translation (such as David R. Slavitt's highly readable The Theban Plays of Sophocles), does force questions we might not ask otherwise; we plum a depth from Slaight's work which may not be actually present—Who is speaking now? What erotic act is being performed and between whom? How does time sync between the two works?

The thing about vague writing is that it allows for endless interpretation—in this case, either an astute critical commentary on the endurance and universality of Sophocle's play or a freshman literary trick that goes a little something like “it means whatever you want it to mean.”

So, does The Antigone Poems earn its place? It does not possess the originality or scope of Anne Carson's 2012 translation Antigonick, with its bizarre illustrations by Bianca Stone, and it does not move or engross as fully as Slavitt's beautiful, lean translations. It does not cause a stir or comment politically. Deconstructed, neither the fragments nor illustrations of The Antigone Poems fully stand up on their own.

But when consumed as a whole—with a familiarity of the source text, with knowledge of the publication as a memorial to a mysterious death, with the beautiful design and thick paper in hand—the work has the lovely quality of an artifact attempting to surface.

Marie Slaight has worked in Montreal, New Orleans, and Buenos Aires as a writer, producer, and performer for film, theatre and music. Her poetry has appeared in American Writing, Pittsburgh Quarterly, Poetry Salzburg, The Abiko Quarterly, New Orleans Review and elsewhere. She is currently the director of Altaire Productions & Publications, a Sydney-based arts production company, which has been involved in independent New Orleans music and such films as the award-winning documentary Bury the Hatchet, Kindred and Happy Baby. The Antigone Poems, written in the 1970s and a collaboration with artist Terrence Tasker, is her first published collection of poetry.

Beth Steidle is a writer, illustrator, and book designer currently living in Brooklyn, NY. Her work has appeared in Fairy Tale Review, Drunken Boat, DIAGRAM, and several print anthologies. Her first book,

Beth Steidle is a writer, illustrator, and book designer currently living in Brooklyn, NY. Her work has appeared in Fairy Tale Review, Drunken Boat, DIAGRAM, and several print anthologies. Her first book,