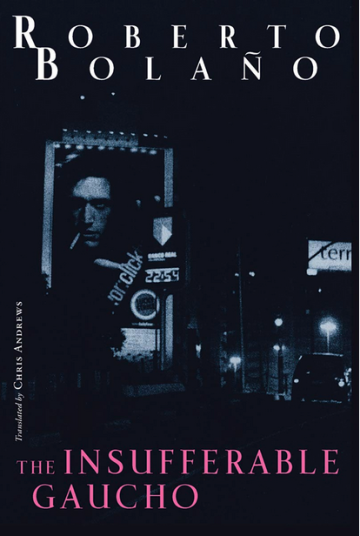

Roberto Bolaño's - THE INSUFFERABLE GAUCHO

The most recent in the outpouring of Roberto Bolaño translations is The Insufferable Gaucho, a collection of short stories and two essays. After finishing the opening story “Jim,” I surmised, dejectedly, that this was a collection of B-sides, stories that Bolaá±o did not see fit to include in his previous collections, released now only to capitalize on his wave of popularity. But a few more pages in, I realized that this wasn't quite the case. It wasn't that the stories were lesser, exactly - it was that in tone, in setting, in taste, they didn't feel anything like Bolaño's other works. They felt like stories by Borges. It sometimes seems like every review of the late Chilean author must mention the name of the late Argentinean. Bolaño has been called “Borges' wisecracking, sardonic son” in the New York Times Book Review, and El Pais wrote that The Savage Detectives is “the novel that Borges would have written.” But though Bolaño 's works have displayed Borges' general influence, many authors have ‘borrowed' Borgesian meta-fictional devices.

To see Borges and Bolaño's names linked together has often made my eye twitch. That is, until now. In The Insufferable Gaucho, we leave Bolaño's usual Chilean émigrés, whores, poets, and gangsters, and have, instead, horses and knife fights, strumming guitars and, of course, gauchos. We have the theme of recovering honor in a changing, shameless world. We have Bolaño's homage to Borges. The homage appears deliberate. The title story centers on a respected judge named Pereda who leaves Buenos Aires to live on his family's decrepit estate on the Pampas. In the first few pages he remembers Borges' "The South," and the rest of the piece plays out like a retelling of Borges' original.

And while it is usually hard to catch a breath during Bolaño's mesmerizing paragraphs, the narration is here far more relaxed and mature - close to Borges' typical detachment. In "Alvaro Rousselot's Journey," too, Bolaño seems to have consciously shifted his style. As an Argentinean author tries to track down a Parisian screenwriter who has turned his books into films without permission, the pace is slow, the tone restrained - each sentence stands on its own, each action is carefully described, as if originating in the mind of a long distance runner.

Bolaño's Argentina is nevertheless one generation removed from Borges'. After the Argentinean economic crash, the gauchos in Bolaño's redaction are pathetic and weak; they get around on bicycles instead of horses, and hunt rabbits instead of herd cattle. Pereda's insistence on riding horses, raising cattle and having knife fights – even when they are absurd - is an attempt to re-establish the honor of the gaucho, the honor they had in the stories of Borges.

Though Gaucho takes on new settings and subjects, Bolaño doesn't entirely leave off his underworld interests, tweaking them with his twisted imagination to produce stories such as “Police Rat,” a deadpan first person narrative about a rat detective attempting to solve mysterious serial murders of baby rats. The rats have common names, philosophies, and their own methods of investigation. There is no irony here. Though I'd be hesitant to use the word allegory, we know the story is symbolic when the detective, Pepe the Cop says: “It's already too late, I thought, for everything. When did it become too late? Weren't we damned right from the origin of our species?”

The two essays are Bolaño's own, separate from the Borgesian stories. Whereas Borges' fictional and non-fictional styles are distinct, his fictions enigmatic and his essays crystal clear, Bolaño's essays are written with the same urgency as his stories. “Literature + Illness = Illness” addresses the intrinsic human state of inner chaos: “Dionysus is to blame for everything.” Although Bolaño writes that this “illness” cannot be cured through the pursuit of travel, sex, or art - paths that lead “nowhere” - these paths must be followed since they lead to the loss of self, as "the self must be lost, in order to find it again.” Clearly, this essay was written by an author facing the abyss of his impending death, trying to figure out what the summation of his life can add up to. In this case, the sum is nothing. But nothing might be the goal.

The second essay, “The Myths of Cthulha,” is so sardonic that it's possible for a reader to miss Bolaño's mockery as he states the “public is never wrong” and advises us all to read best-sellers instead of serious literature. Actually, I'm still not sure if he is being sardonic.

The fiction in The Insufferable Gaucho is an ode to the godfather of Latin American literature and should be understood as no more than that. Bolaño cannot do what Borges does. What Borges accomplishes in five pages takes Bolaá±o thirty-five. Roberto Bolaño may be the most important figure in contemporary literature, but there is and can only be one Jorge Luis Borges.

Roberto Bolaño wrote the novels The Skating Rink, By Night in Chile, The Savage Detectives, and 2666, among many others. He died in 2003.