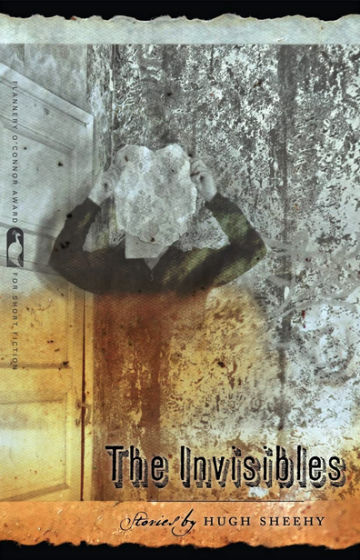

THE INVISIBLES by Hugh Sheehy

The short story has long been a hotbed for the wicked, off-kilter, anomalous, and unnoticeable. Blame the brevity of the genre's form, which allows for a degree of leniency with backstory, character development, and the logic of a fictional universe -- a suspension of disbelief perfect for portrayals of fringe society. See Flannery O'Connor's The Misfit, Joyce Carol Oates' Arnold Friend, John Cheever's Swimmer, Kafka's Gregor Samsa, nearly anyone dreamt up by Robert Coover, Rudyard Kipling's White Seal, and so on.

Hugh Sheehy's debut collection, The Invisibles (University of Georgia Press), which won the Flannery O'Connor Award for Short Fiction in 2011, fits solidly within this tradition. In the opening story, "Meat and Mouth," an assistant teacher, Maddy, waits in the Grace Evangelical Church and School with one of her young students, Luke, whose father is perpetually late picking him up. Maddy is disenchanted, and has a habit of spiking her coffee with vodka. Luke is unwashed and underprivileged, preferring to be called Davey, the name of the larger boy who bullies him. As snow accumulates on the "pale brown trees and bald fields," two meth-heads with "bluish skin" and "clinking chains" appear.

I don't want to spoil it for you, so let's just say that one person ends up with a slit throat, while others end up locked in the basement, huddled against the furnace. Here, as throughout The Invisibles, the characters flounder as the plot is propelled by an omniscient, almost decadent, force. The author's hand is an unrelenting presence. You just know that not much good is going to happen. And you're not quite sure this is a world you want to enter, like putting your head inside the lion's mouth. At moments, "Meat and Mouth" feels hyper-realistic -- Maddy a bit too valiant, Luke a bit too whimpering, Meat and Mouth a bit too sadistic-Tweedle-Dee and evil-Tweedle-Dum, the world a bit too dismal. Without an O'Connor-esque fusion of satire or irony, it can be a bit heavy-handed. But it grows on you.

As the collection progresses, it does not necessarily become less grotesque, but the gruesomeness and hyperrealism are tempered with segments of profound lyricism, deepened insight, and universal themes of grief, loneliness, and a fear of disappearing. In the collection's eponymous story, an invisible is defined as "a person who is unnoticeable, hence unmemorable." A mother describes the phenomenon to her young daughter, Cynthia:

She brought home reports: a woman licking stamps at the post office, an anguished old man in line at the bank, a girl crying by a painting in the museum. The library crawling with them. 'Remember, Cynthia, you're an invisible to,' she said. 'Just like me. We're in it together. Forever.'

Years after Cynthia's mother vanished without a trace, Cynthia's friends, also invisible, are kidnapped and never found. The narrative weaves in and out of Cynthia's thoughts and dreams as she tries to comprehend these losses, which Sheehy deftly renders universally personal -- we feel for Cynthia because we too have lost, we too have felt invisible, we too wonder where we have gone. The premise of "the invisible" forms a clever linkage from story to story. Sheehy creates a nonstop parade of over-ordinary figures and characters so down on their luck they've all but faded out. We understand that we wouldn't notice them except under extraordinary duress: the miscarriage of an unborn child, prematurely nicknamed Henrik the Viking; the disgraced professor standing before a mural of Lazarus rising, completely devoid of memory; a genial neighbor found "cut to pieces in the basement"; a drug-addicted Prodigal Son encountering an accident in the midst of a pitch-black blizzard.

Certainly, Sheehy lords over a wild world, tossing flares into its darkness, revealing what was once invisible and what remains painfully intimate. It is in these most intimate moments, when we are inside the character's thoughts and memories, that the best writing emerges. "After the Flood," in which a man covers up the crimes of his degenerate stepson, opens with perhaps the most powerful lyrical sequence:

The Mississippi swells up and covers the town and the surrounding forest, devastating all visible creation. Hundreds of egrets fly north; there is no counting the dead. The steeple of St. Francis of Assisi marks the submerged churchyard of obelisks, crosses, and angels. Broken boats and tables drift under convulsing clouds stitched up with lightning. There will be no going back from this deluge, no recovery of the lost civilization, no afterward.

These levels of language play, however, are quickly revoked as the narrative returns to the waking, outside world, where the texts morphs into a sparser plot-propelling prose. This style of writing imbues the entire collection with an odd, arrhythmic pulse, lounging followed by frenetic motion. Even if not 100% successful, this is structurally compelling in its own right, a jauntiness that underscores the instability of the characters themselves.

Sheehy's world is not a place for relaxing or loitering. It's not a place for having fun. But ultimately the stories are compulsively readable and disturbingly engrossing. Personally, I like to imagine O'Connor's Misfit, Bible salesman, and hijacked prosthetic leg carpooling out to Sheehy's swampland to meet with his meth heads, his disappeared, his dead. It would be the world's bleakest picnic, but I'd still eat the food.

Hugh Sheehy is a lecturer at Yeshiva College and has previously taught at Kennesaw State University and Georgia State University. Sheehy received his MFA in creative writing from the University of Alabama. His stories have appeared in publications including Glimmer Train, Kenyon Review, and Best American Mystery Stories.

Beth Steidle is a writer, illustrator, and book designer currently living in Brooklyn, NY. Her work has appeared in Fairy Tale Review, Drunken Boat, DIAGRAM, and several print anthologies. Her first book,

Beth Steidle is a writer, illustrator, and book designer currently living in Brooklyn, NY. Her work has appeared in Fairy Tale Review, Drunken Boat, DIAGRAM, and several print anthologies. Her first book,