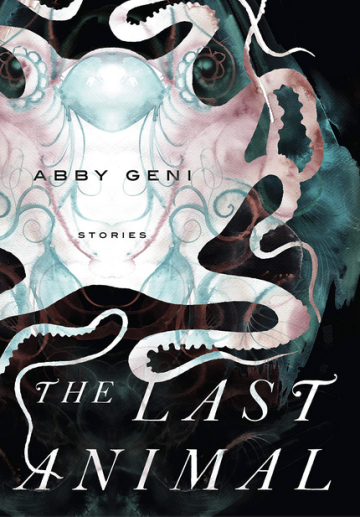

THE LAST ANIMAL by Abby Geni

Abby Geni's debut short story collection, The Last Animal (Counterpoint Press), seeks, in her own words, to explore "one of the great illusions of the human experience... that we are somehow outside of nature—beyond the food chain—that we are not animals ourselves." It's an enduring premise that still feels ripe with possibility—a post-Romantic examination of man vs. nature, prehistory vs. technology, intellect vs. instinct. It's eons subtler than Planet of the Apes, far less satirical than Animal Farm, less epic than Moby Dick, and absent of anthropomorphism. Rather, it's a plainspoken, earnest collection that finds its home somewhere between Megan Mayhew Bergman's quietly moving Birds of a Lesser Paradise and Lydia Millet's darkly absorbing How the Dead Dream.

Like Bergman and Millet, Geni's universe is an exotic place. Most of the ten stories are populated by anomalous-but-within-the-realm-of-possibility characters—an octopus handler, a dying, airplane-building hobbyist, a beetle specialist—all grappling with universal troubles: fidelity, familial dysfunction, loss, grief. Yet even here there are outliers, characters both overly recognizable, nearly to the point of being trite, and downright fantastical. "Dharma at the Gate" chronicles the all too familiar self-destructive relationship between two teens—suicidal boy and large-dreaming girl—while a trusty dog paces alongside. In "Landscaping," on the other end of the spectrum, a child literally demands the world from his two mothers, insisting on a river and a mountain before "he walked on his own, step by step, across the black and empty miles," eventually setting foot on the moon. These are not people you'd truly want to meet, but people best admired as if in a zoo, enacting dramas better observed than closely handled.

Case in point is the opening piece: "Terror Birds." It's an Arizona ostrich farm drama, told through alternating first person perspectives between a mother and her young son. When Jack witnesses his father having sex with a farmhand—on their patio, in the moonlight, the woman's arms "moving as though she were making a snow angel" (is this a thing I don't know about?)—and later sets loose hundreds of ostriches in half-crazed retaliation.

Here we feel privy to insanely intimate acts and, yet, it's difficult to achieve closeness. In a desert of unlikeability, Jack's mother seems often oblivious and timid, Jack's father is a flagrant adulterer, and Jack is ungraspable, his narrative yo-yoing between that of a child ("I liked the Loch Ness plesiosaurus and the blue whale, but for my money, the Terror Bird was the most interesting.") and an adult ("In a stagy, quixotic move, my father took up my mother's hands and began to waltz with her in the watery light."). This sense of distance between the reader-as-voyeur and the protagonist-as-watched-figure feels at odds with the collection's seeming desire to elicit emotion, perhaps the result of stories which can feel both overly polished and not yet fully edited.

It's possible that Geni's pedigree precedes her too greatly: she is a graduate of the Iowa Writer's Workshop (an accomplishment which has the tendency to elicit vastly diverse reactions), recipient of an Iowa Fellowship, first place winner of the Glimmer Train Fiction Open and Chautauqua Contest, with a mention in the 2010 Best American Short Stories. Which is to say: if you read the bio before the book, your expectations are on high alert. And, depending on who you are, it's a resume that either primes your heart for affection or leaves you prepping for a fiery critique of the so-called "Iowa story."

That being said, the majority of the stories deserve high marks for technical execution: plots that sail along geometrically blessed inverted checkmarks, snappy hooks, quintessential postmodern non-endings, and a pleasing ratio of dialogue to prose. Opening paragraphs are primed for action, as "Isaiah on Sunday" begins: "He wakes in a panic... Someone is pounding at his front door." And, like Vonnegut's cup of water, the characters' desires are firmly identified, but less easily satisfied. In "Silence," for example, the terminally ill narrator wants to complete construction of his small airplane, an object which functions as a somewhat obvious metaphor for a truer want—a peaceful departure from life.

"Captivity," recipient of the first place prize in the Glimmer Train Fiction Open, deserves its own recognition as the standout piece. It's the story of an octopus handler who has, at the age of 31, moved back in with her mother and is still struggling to come to terms over the mysterious disappearance of her brother. The unusual plotline gathers weight within the story's solid construction and consistent pacing, while evocative settings—“A few hanging plants spilled over their containers and trickled like kelp towards the floor.”—generate an aquatic aura. There are a number of clunky moments, however, when Geni succumbs to the Chuck Palahniuk/Dan Brown dispersing-of-interesting-facts disease, in this case an awkward listing of the characteristics of octopi.

As a whole, what The Last Animal lacks is true fervor, lush language, or bold, shocking gestures. More focused on functionality than experimental form, the stories remain rooted in straightforward prose and practical pacing. But Geni is smart enough to know the equation: conservative element plus bizarre element can equal satisfactory compromise. In this case, her curious cast and unexpected plots rescue the stories from descent into the pit of the overly ordinary. It's not all that dissimilar from the dressing-like-a-lady lesson: high-neckline pairs with short skirt, long skirt pairs with plunging neckline. Wear a turtleneck and a floor skimmer, and you risk looking frumpy. Wear a plunging neckline and a mini and you risk being mistaken for a lady of the night.

So The Last Animal is safety in followed rules. This, in its own way, is fine. There is a distinct comfort in the eminently understandable. Personally, I prefer something a bit more scandalous. Then again, I've never been voted Best Dressed.

Abby Geni is a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop and the recipient of an Iowa Fellowship. “Captivity” won first place in the Glimmer Train Fiction Open and was listed in 2010 Best American Short Stories; it was also selected for inclusion in New Stories from the Midwest, published by Ohio University Press. Her stories have also received Honorable Mentions in the Kate Baverman Short Story Prize and in Glimmer Train's Very Short Fiction Competition. She lives in Chicago, where she is at work on a novel.

Beth Steidle is a writer, illustrator, and book designer currently living in Brooklyn, NY. Her work has appeared in Fairy Tale Review, Drunken Boat, DIAGRAM, and several print anthologies. Her first book,

Beth Steidle is a writer, illustrator, and book designer currently living in Brooklyn, NY. Her work has appeared in Fairy Tale Review, Drunken Boat, DIAGRAM, and several print anthologies. Her first book,