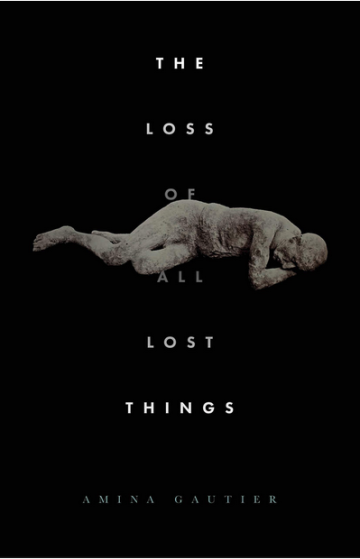

THE LOSS OF ALL LOST THINGS by Amina Gautier

“He has learned that this is something one can do with words, stretch them into softness and push them past their meaning. Take him, for example. He prefers the word lost instead of taken. Lost is much much better. Things that are taken are never given back. Things that are lost can be found.”

These lines, from Amina Gautier's opening story “Lost and Found,” reverberate through the entire collection: the capacity for language to both define and deconstruct our world is ever-present. The fifteen stories in The Loss of All Lost Things (Elixir Press) force us to dismantle our understanding of loss, to question what can and cannot be misplaced, to examine failures in fidelity, absences in emotion, lapses in judgment and leaps in behavior—all in pursuit of human connection.

“Lost and Found” introduces us to Gautier's finely-honed prose, equal parts evocative and unorthodox. The unnatural constructions seem to complement the interruptive nature of the unnamed boy's kidnapping, “he remembers only: being pulled into a car; waking up and finding himself tied to a chair in an unrecognizable room of an unrecognizable house.” The language mimics the lost boy's suddenly skewed world, the jarring disintegration of his identity within the distorted narrative of his kidnapping. The absence of explicit explanation or description of the perpetual sexual abuse both obscures and renders a potent experience of horror and revulsion.

The brilliance here is Gautier's decision to give only the boy's perspective, his belief that his family has forgotten him or simply prefers him lost. We are left hollow, and at the start of the following piece, “The Loss of All Lost Things,” yearning for resolve or redemption. Here the story of two parents torn apart by their son's disappearance and battling their own imperfections recolors the previous narrative—yet the stories succeed because they are separate. It is harrowing for the boy to believe he has been forgotten because we are not entirely sure he is mistaken; when in the “The Loss of All Lost Things” we discover a mother's desperate desire for her son's kidnapper to be a woman loving him as her own child, it is all the more devastating because we know, from the previous story, who the kidnapper really is.

Throughout, Gautier leaves emotional breadcrumbs—nourishment, lost children, motherhood, sexual fascinations, and reoccurring physical elements—that serve to enhance and complicate our reading. Each subsequent time we meet a lost child, whether ill in the womb or absent from a marriage, we are reminded of the earlier children. The stories enter into conversation with one another. In “The Loss of All Lost Things,” the most prominent and perhaps most successful piece in the collection, the parents compare the loss of their son to the loss of people and buildings and life. The physical world, a forgotten world, becomes a means through which we can access their loss. The mother finds posters of her missing son piled in garbage: there we see a physical embodiment of her grief, her fury. She cannot fathom her son, in flesh and blood, in the hands of a monster. The closest she comes to confrontation is looking at a decomposing photograph. What this reveals and doesn't reveal of her internal trauma is exquisite.

While both subtlety and control are central to Gautier's prose, her writing sings in a wide range of registers. A second-person perspective in “What Matters Most” is a much-needed release from the intensity of first person narration up to then dominant in the collection. In “Most Honest,” the musicality of thought is electric, raw: “...I am looking at the list and thinking of this date and pouring milk over my cereal and missing my wife and now the bowl is filled with milk and my cereal floats in the milk and milk is now spilling over the bowl and down onto my bare feet and I'm still looking at the list and missing her hard, so hard.”

Nearly all of these stories begin with a slightly odd, commanding opening. In “A Brief Pause,” “Cicero Waiting,” and “As I Wander,” we are propelled directly into explorations of human beings facing death, divorce, violence, and loneliness. By refusing to overtly explain her characters and their subsequent actions, Gautier establishes an unwavering authorial power that allows her to unapologetically dive into territories many writers might shy away from. Sex is both a weapon and a form of salvation for women and men alike; socio-political, racial, and economic judgments and injustices are gorgeously infused into the text without becoming didactic. Race is often consciously evoked by reference to skin tones, children's dolls, or fascination with “hair [one character] could not fathom.” These tensions become the fabric of the stories, the means through which the language itself moves the readers' psyches.

“Resident Lover” is representative of the collection in that it stimulates the type of internal rumination found throughout the collection, but it is a bit overt. The story follows a man whose wife has recently left him for an artist she met at a residency—he then enters into an artist residency, in search of something like redemption. The story becomes a meditation on art making, a self-reflexive narrative about the power or lack thereof in craft. “His wife's poems could not sneak up on anyone, could not get close enough to make one flinch and could never make a person shiver.” At times Gautier's characters' actions prompt questions of plausibility, motivation, and authority; we often find ourselves wondering whether we know them well enough. Like in “Resident Lover,” in “What Matters Most,” “Intersections,” and “Directory Assistance,” the narratives conclude with shifts that do not feel entirely warranted or earned. “Directory Assistance”, a story so fraught with love, ends with a fantasy about union strikes. These moves come as an unnerving surprise we are not always equipped to appreciate. This is not to say that those stories are unsuccessful; on the contrary, they are moving. But we too often ask: why are we left here, why did we make this turn, what does this turn mean? We wish to believe they are capable of transforming in ways that are profound, yet those transformations can be opaque.

By Gautier's work I am reminded of “The Writing” by Slovenian poet, TomaÃ…Â_ Ã…Â alamun: “As in / love / everything / comes out. / The words tremble / if they are / right. / As the boy / trembles in / love, / the words / tremble on paper.” She can make us tremble, and quite often, she does. The Loss of All Lost Things is in many ways a tremendous feat. It thinks on what it means to be human through our experience of loss and our understanding of the world.

Amina Gautier is the author of three award-winning short story collections: At-Risk, Now We Will Be Happy, and The Loss of All Lost Things. At-Risk won the Flannery O'Connor Award, The First Horizon Award, and the Eric Hoffer Legacy Fiction Award. Now We Will Be Happy captured the Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Fiction and the Florida Authors and Publishers Association President's Book Award. The Loss of All Lost Things was awarded the Elixir Press Award in Fiction. Gautier is the recipient of numerous grants and fellowships. Her work has appeared in such literary journals as Agni, Callaloo, Glimmer Train, Iowa Review, Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, Southern Review, and StoryQuarterly. She teaches in the MFA program at University of Miami and divides her time between Chicago and Miami.

Jenessa Abrams is an MFA candidate in fiction and literary translation at Columbia University. She studied creative writing and child and adolescent mental health at New York University. Her fiction has been published in Bluestockings Magazine and The Grief Diaries. A short film, which she wrote and produced, was selected for the Cannes Short Film Corner in 2013. She lives in New York, where she's at work on a short story collection.

Jenessa Abrams is an MFA candidate in fiction and literary translation at Columbia University. She studied creative writing and child and adolescent mental health at New York University. Her fiction has been published in Bluestockings Magazine and The Grief Diaries. A short film, which she wrote and produced, was selected for the Cannes Short Film Corner in 2013. She lives in New York, where she's at work on a short story collection.