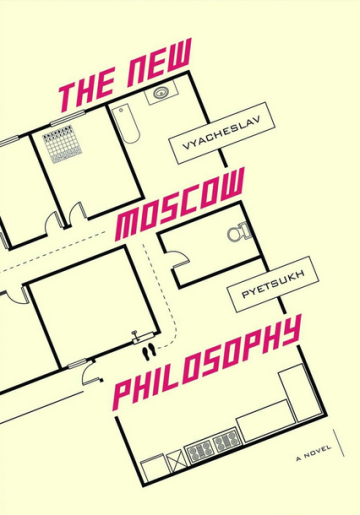

THE NEW MOSCOW PHILOSOPHY by Vyacheslav Pyetsukh

‘The meaning of life is purely a Russian fabrication. We fabricated it for the very same reason the Asians fabricated Buddhism: presumably from want of life's basic necessities.'

Vyacheslav Pyetsukh's THE NEW MOSCOW PHILOSOPHY reads like an anthology of short stories from Russia's finest writers of prose. A companion to Gogol, Turgenev and Ivan Bunin, the myths and legends of this vast land seep into the novel, mordantly intertwined with the contemporary politics of the late-Soviet period – when the novel was originally written. Published by Prague-based Twisted Spoon Press, this is the novel's first English edition, arriving over twenty years since its original Russian publication in 1989. Fortunately, the English reader, perhaps gaining from the wait, has the benefit of historical hindsight to inform their read of this darkly humorous, philosophically sophisticated ‘whodunit' mystery.

Faintly echoing Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment, the novel begins with a heightening sense of suspicion over the disappearance, and possible murder, of a landlady – Alexandra Sergeyevna Pumpianskaya. Set in Apartment 12 of a decaying building, found in a Moscow suburb, Pumpianskaya's tenants and neighbours have disliked her ‘since time immemorial and always oppressed her in whatever way possible'. Having lived in her dwelling for many years, there are suspicions surrounding her former bourgeois heritage, as well as her continued Tsarist sympathies: once, in reference to Tsar Nicholas the Bloody, she called the monarch ‘His Majesty'.

Never leaving the confines of the building - we are trapped with the thirteen characters (mercifully listed at the start) that appear within the book's densely crowded pages. Offering the reader a chance to observe a microcosm of Soviet society in the era of Glasnost, one listens in as conversations concerning personal beliefs and existential theories mingle with irreverent discussions about the Russian-character, as well as dealing with increasingly paranoid suspicions over the death of Pumpianskaya. And it is here, through the narrative of the murder mystery, that Pyetsukh, an ever present narrator, adds his own footnotes and insights to the proceedings. This makes THE NEW MOSCOW PHILOSOPHY a mixture of fiction, philosophy, political commentary, as well as literary criticism, all within a relatively short 186 pages.

Spread across four days, Friday to Monday, the subtle detective story introduces us to Pumpianskaya's fellow residents and tenants in Apartment 12. Such a tightly packed space breeds an atmosphere of animosity, where everyone knows each other's business and habits. A rivalry develops over Pumpainskaya's room, the largest and most sought-after. The days pass, and with appearance of the local police – in the form of Inspector Rybkin – speculation grows as to what happened, with numerous theories presented. Despite the narrative seeming secondary to the philosophical discourse, the most entertaining parts of the novel can be found in the conversations of the residents, often voicing their amusing and subversive views.

“Hello, boys!” suddenly rang out a voice behind them, and the posse turned round.

It was Lev Borisovich Fondervyakin standing in the middle of the kitchen, wrapped in a striped sheet. “What've you all crowded in here to peep at so late?”At these words Fondervyakin playfully bowed his head, and his bald patch began to shine like a newly minted five-kopeck coin. No one answered him.“Here's what I think,” Fondervyakin began to say. “None of this is as simple as it might seem at first glance. Most likely there's some age old story here: collaboration with the Nazis, or even a link to a foreign spy mission now liquidating its agents...”“Shame on you, you old coot,” responded Chinarikov. “What are you going on about – it's beyond comprehension! Next you'll be saying Pumpianskaya had connections to the spirit world!”“You bet I will! It's no coincidence that Yulka Golova saw a ghost!”

Much has been written about this novel being a Crime and Punishment parody. Whilst present and palpable, it is not the driving force of the story as many have suggested it is. More honestly, Pyetsukh presents a discourse on the importance of literature in Russian life, one that encompasses the ideas of many authors and thinkers. Common themes emerge: the inability of Russian to embrace a cultural ‘Europeaness', and the relationship between good and evil. For example: "Good and evil exist, I would say even coexist, in the same way as fire and water, heaven and earth, man and woman...If there were no evil, there would be no struggle or movement, which is to say – life.” However, it is the fractured metaphysical relationship between fiction and human existence that interests Pyetsukh the most:

‘....compared to literature, life is much more mottled, incoherent, variable, details, tedious....perhaps literature is indeed life, in other words, the ideal it its construction, the standard for all weights and measures, while so-called life comprises a sketch, avenues of approach, a blank, and in the most felicitous situations – a version. More than anything it looks as if literature, word of honour, is the fair copy and life a rough copy, and not even the most useful.'

The grandiosity of Pyetsukh's aim is achieved by maintaining a tone of self-deprecation throughout, mocking his own aspirations and philosophizing - an example, perhaps, of his own hesitation towards the changing political atmosphere at the time. In an age were ideologies affected the very basic mechanics of everyday life for millions, the apprehensions of the THE NEW MOSCOW PHILOSOPHY towards ideas can be understood – this is also where the spirit of dark, often hilarious satirical humour, creeps into the book. With an excellent translation by Krystyna Anna Steiger, this story presents a Russia grappling with the reawakening mysticism of its past traditions and a pragmatic realism instilled through over sixty years of Soviet domination. Fortunately, Pyetsukh has weaved this into a humorous, insightful, easy-to-follow novel, which overall offers an immensely enjoyable and educating read.

VYACHESLAV PYETSUKH

Born November 18, 1946 in Moscow, Vyacheslav Alekseyevich Pyetsukh is a prolific writer of both fiction and essays. Having taught high-school history and Russian for more than a decade, he embarked on a successful career as one of Russia's most published contemporary authors, quickly becaming a major figure of the late-Soviet period and thereafter. He has published fifteen collected editions of his work, and both his essays and short stories appear regularly in leading Russian journals. Often meta-literary, his writing has been placed in the context of 1990s Russian postmodernism alongside such writers as Tatiana Tolstaya, Victor Erofeyev, and Evgeny Popov, and as a public intellectual he has often been compared to the likes of Vladimir Soloviev, Nikolai Berdyaev, and Alexander Solzhenitsyn. In English, his work has appeared in The Penguin Book of New Russian Writing (edited by Erofeyev) and a number of journals. A short story, "Me and the Sea," won the 1999 Emily Clark Balch Prize of the Virginia Quarterly Review. Pyetsukh was awarded the prestigious Pushkin Prize in 2007, and received a National Ecological Award in 2009, for his "creative contribution" to promoting environmental issues in Russia, and a 2010 Triumph Award for excellence in the arts and literature. Pyetsukh and his wife Irina, an art dealer specializing in avant-garde painting, divide their time between Moscow and a village in the Tverskaya region.

Richard Jackson is a PhD candidate and freelance writer from the UK. He enjoys writing about Central and Eastern Europe and has submitted articles to journals such as Transitions Online and Literature Across Frontiers. He manages and writes for the website ‘Lemberik' –

Richard Jackson is a PhD candidate and freelance writer from the UK. He enjoys writing about Central and Eastern Europe and has submitted articles to journals such as Transitions Online and Literature Across Frontiers. He manages and writes for the website ‘Lemberik' –