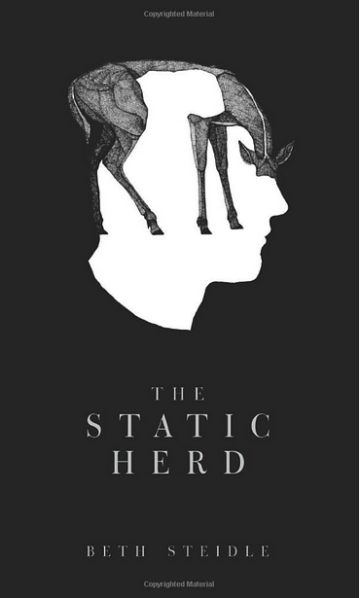

THE STATIC HERD by Beth Steidle

If you're looking for proof that language naturally carries the mineral ore of poetry within it, turn to Beth Steidle's The Static Herd (Calamari Press). Steidle's new book is prefaced by the etymology of “deer,” a gradual “change in sound and appearance” that possesses such an effortless and effective resonance it's worth reproducing in full:

From Old English deor 'animal, beast, any sort of wild creature.' From Proto-Germanic deuzam, 'animal' (as opposed to man), and dheusom, 'creature that breathes.' Related to Lithuanian dusti (to gasp, to sigh), Lithuanian, dvesti (to exhale, to perish), Russian dusa (breath, spirit), Russian dvochat (to cough), Sanskrit dhvaáÂ_ÂÅsati (he falls to dust).

In the history of the word there is not only a metamorphosis from beast to human, but also a declension, measured in breath, from vigor to the final exhalation. The descent seems too quick, but the deer is a paradoxical creature, both virile stag and vulnerable prey, an emblem of power in one moment, and in the next, a reminder of mortal weakness. Little wonder that Steidle finds valuable raw material in the etymology of the word, and also chooses the animal as the emblem for her meditation on the fall of the patriarch. Fathers have been dying since the beginning; but when it happens to you it is the first, last, and only time it will ever occur. Consequently, it is particular, and as an event, fleeting.

Steidle's father died of cancer last year and the The Static Herd is a condensed record of his last six years, from the cancer's first detection onward, that works like the quieting solution added to microscope slides in order to slow down protozoans. Under her gaze, the impulses of emotion and memory, which work in an intense but temporary way at such times, are halted long enough to be perceived and analyzed. What results is an examination of the final decline, or more properly, of its duration, as experienced by both parent and child. “The modern death is a process of extension, bred like the long bellies of useless dogs. Of great lengths and infinite strings,” she writes. It lasts a long time, but still needs to be slowed down in order to be processed.

Given its territory, The Static Herd could be a lament or a record of a grief observed. But Steidle is not only curious, she's also hospitable to darkness. “We asked the darkness if it had eaten. We said to the darkness, goodnight ladies and gentlemen.” Consequently, she has produced something altogether more interesting: an elegy that is also an inquiry into how language and images formalize our apprehension of mortality and our understanding of death. Like the deer, it is a paradoxical creature: solemn but humorous, painful but pleasant, and despite its moribund subject, pulsing with vitality.

The book is a hybrid of medical examination records and personal recollections resembling a formal report, with text categorized under a series of labels: history, findings, impressions, technique, procedure in detail, operative note, course (of treatment). Spaced throughout are a series of drawings by the author, depicting a deer in decline, as well as an unsettling set of CT scans. Objective findings exist in tension with their subjective counterparts. “There is partial effacement of the sylvian fissure on the left at the level of the basal cisterns. There is mass effect. The appearance is concerning. The sylvian fissure cleaves the world in two. Memories of birth swirl at the base of the trench.”

Frequently, clinical language corrupts the narration of subjective experience, mirroring the way that the language of medicine becomes a common element of our discourse when we are in sustained proximity to it, and relying on it to make illness intelligible. Steidle is fascinated by the ways this intelligibility is produced, and The Static Herd shows how terminology and data construct the body, as well as diagnose and treat it, and then in turn measure the material effects produced by this linguistic constrainment. “As the body reduces finitely,” she writes, “the numbers increase exponentially.” The absolute precision that is the goal of scientific language, that is, the aspiration toward a complete correspondence between what happens to a body and how it is described in language, is impossible to fully realize, since it would be dependent on the eradication of language's constitutive slipperiness.

Most of the time we ignore this impossibility, and perhaps no more strongly than when the mortal reality of the body is imminent, but this is a truth that Steidle's quieting solution suspends, and it's fascinating to observe her poetic language working in direct antagonism to its aims. At points the scientific language simply breaks down: “There is a. There is. There is. There is no.” Or elsewhere: “There is mass effect. The appearance is concerning.” This is language that searches for its object but never identifies it, that inclines toward meaning without ever producing it.

Later, following her father's diagnosis, under “INDICATIONS FOR PROCEDURE”, she writes: “The patient was presented with the options. The family was presented with the options. Everyone subsumed to what was recommended.” Neither options nor recommendations are delineated, however; the language momentarily admits its own limitation; it is not substitute for the thing itself. “The field guide,” she writes, “is a notoriously useless catalog of images which cannot be matched to their living counterparts.” That we inevitably depend on it anyway, a truth both painful and humorous, is one of Steidle's core insights, embodied by the CT scans that threaten at points to metastasize the text. They are the distressing visual supplement to the shortcomings of language, even as they also fail to present the real of cancer – a failure perhaps enhanced by their grainy, pixelated nature. In the meantime, Steidle's subjective impressions not only unsettle meaning, but also temporal linearity and family history. Even as her father declines from deor toward dhvaáÂ_ÂÅsati, she is still discovering new things about him. The findings are critical. It's not until she reads an exam report from 2011, three years before his death, that she learns his date of birth.

There is mass effect: anarchic life, like an uncontrollable growth, intrudes. Life does not stop for death, nothing slow down in an orderly fashion, and beginnings interrupt endings. “A deer midbirth will run nonetheless,” she writes. And even as she witnesses her father's decline, she is also reflecting on her own fate, and not just her own decline, but the fate of more life to come. What makes The Static Herd such a potent meditation is this uncommon awareness that even death is fleeting. Her father dies for a long time, and when it comes it is no surprise, undertaken of his own accord. And yet “everything moves away so quickly.” His death occurs just before her birthday, and immediately more births, and more deaths, are already arriving, relegating this momentous one to the past while it is still all too present. She writes:

Today, we feast. Tomorrow we belly up with regret. Tomorrow I intend to refuse all things. It's been proven: the universe is hurtling outward. My brother's wife puts her own on her stomach and keens. She is losing the baby. I am sitting so close. I suspect but do nothing. You know it's nothing more than a tadpole at this stage. My love is drowsy when I give it at all. I watch the tablecloth. I wait for cake. I lie down with the hexed dog. It was a birthday party, for god's sake.

The relentless hurtling outward effaces even the permanence of death. “This particular firmament, this particular alignment of tumor and organ will not repeat,” writes Steidle, and it contains a hint of plea: stop hurtling, for just a moment, for something has happened. Someone has died. This is why it is important to try and formalize experience, even though these formalizations eventually dissolve. And this is why we are interested, as Steidle is, in the aim of scientific language: it represents the closest we're likely to come to snatching something away from the transience of life, including what we usually consider its point of termination. The Static Herd is a necessary reminder that even death, despite its eternal effects, doesn't last very long.

Beth Steidle is a writer, illustrator, and book designer currently living in Brooklyn, NY. Her work has appeared in Drunken Boat, DIAGRAM, Hot Metal Bridge, and several print anthologies.

Matt Pieknik bookmongers in Manhattan and writes in Brooklyn, and his writing has recently appeared in The Paris Review Daily and The American Reader. He's currently at work on a not-quite-sci-fi novella set in vast absence of Detroit.

Matt Pieknik bookmongers in Manhattan and writes in Brooklyn, and his writing has recently appeared in The Paris Review Daily and The American Reader. He's currently at work on a not-quite-sci-fi novella set in vast absence of Detroit.