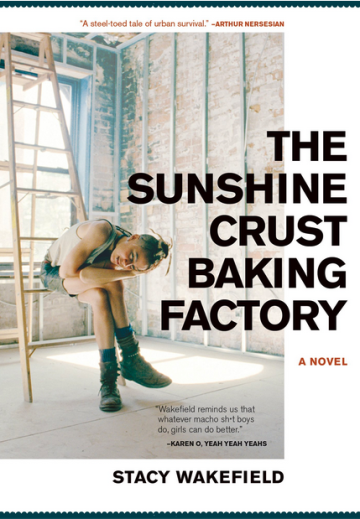

THE SUNSHINE CRUST BAKING FACTORY by Stacy Wakefield

Set twenty years in the past, Stacy Wakefield's debut novel, The Sunshine Crust Baking Factory (Akashic Books), comes at an opportune time to look back at the heyday of the practice of squatting, both in the US and Europe, and consider what has become of it. The verdict is perhaps still a long way out on the ultimate effectiveness of the loosely organized Occupy movement, but, if nothing else, it is the most recently visible manifestation of the legacy of squatting. By combining sit-in political visibility with weeks-long land appropriation, Occupy Wall Street became part of the tradition of squatting as a means of protest. The residential squatting brought to life in Wakefield's novel is its own kind of political statement, but one that is made in everyday life choices.In the mid-‘90s, nineteen-year-old Sid has finally moved to New York City after so many trips down from Connecticut to see punk shows at the fabled community-oriented arts center ABC No Rio. Enamored with how the squatting scene in the Lower East Side seemed to embody the pervading DIY ethics of the day, Sid wants in. She is connected enough to get a part time job selling band T-shirts at ABC No Rio shows, but every one of the existing squats in the neighborhood is filled.

Actual estimates suggest that during that time there was anywhere from 500 to 1,000 squatters spread out around the East Village and Lower East Side in over 30 buildings. That figure isn't much compared to the estimated 30,000 squatters that lived all across London in the late 1970s and 1980s -- when it was fairly normal for young people in artistic trades to claim a spot in an unused residence -- but it's enough to deserve notice.

Ten years too late for lower Manhattan, it turns out Sid is right on time for North Brooklyn, though it doesn't seem that way to her at first. In recent years a modest four-family building near Rodney Street and South 1st would probably sell for somewhere in the area of one million dollars, but twenty years ago Wakefield actually spent a summer living in a squatted building on that intersection that serves as the model for the novel's titular setting. Demographically speaking, the LES and North Brooklyn are now essentially one long neighborhood with a river running through it, but Sid's first impression is one of an enormous divide.

Following her friend Donny's tip about the old factory, there Sid finds her new roommates. Mitch, who first established the squat, works manual labor and often speaks with his back to people. Skip is a street bookseller and poet who somehow doesn't know much of anything about punk, straight edge, or even the definition of the word ‘celibate'. Eddie is “six months clean and counting”. Sid has brought along Lorenzo, a punk rocker from Mexico who leads a band called Disguerro and has come to leave his mark on the NYC scene. Lorenzo is adept at exploiting Sid's unrequited crush on him, Sid less so at keeping that crush from affecting how she handles her new living situation. Every character in the novel is something of a “type”, but Wakefield does a fine job of keeping them from being one-dimensional.

At some point between the first and the last page, the reader will find reasons to like and dislike all of the main players. Skip, for example, who makes such an unimpressive first impression, endearingly comes alive when he reads at a poetry night, only to disappoint again later on. Even Sid has her irritating moments, and Lorenzo isn't a 100% jerk – just a 99% one. Brisk as the story is, the characters -- at least some of whom are composites of people Wakefield met while squatting – are immediate and rub up against you in familiar ways, especially if you lived through the ‘90s and knew people who lived this lifestyle. As the title suggests, the most vivid character in the book is the factory itself. The first floor with its dingy corners and refuse piles, the nascent 2nd floor art space, and Mitch's tidier third floor dwelling – you can practically smell the place, for better or for worse. The old factory holds different potential for each of its inhabitants. It is a white canvas for them to project their individual dreams on. Sid wants an alternative society, Mitch wants as little to do with any kind of society all together, and the factory holds both of those promises for them. Both in Sid's interior monologues and conversations among the house members, Wakefield shows the spectrum of squatting's allure.

The notion of “squatters' rights” has at times been a little romantically exaggerated by some, at least in the US and Britain (certain parts of Europe have perhaps been more relaxed). Yes, if you managed to prove continual occupation of a disused building for a certain amount of time, you could eventually make a claim to live there, but those periods of time were long and could be arduous to uphold. In general, squatters' rights have had more to do with limitations on the way people can be physically removed from residences, and less to do with one's actual right to claim an empty building for themselves. Sadly, in recent years, what rights squatters could claim have come under attack. In 2012, Weatherley's Law made squatting in a residential building a criminal offense in England. Last year, the state of Michigan created similar laws: landlords now have greater power to physically remove occupants, and squatting is a misdemeanor first offense, felony second offense. It might seem logical that Detroit would consider offering up its 40,000-plus abandoned buildings for a squatter's price to encourage young artsy types to come repopulate the failing city, but Detroit is a complicated situation to say the least.

If it had ever been a squatter's paradise, Wakefield illustrates that New York City in the 1990s was a complicated situation as well. All it takes is a small fire in one room of the Rot Squat building in the East Village, and the demolition crews come chasing behind the fire engines at the behest of Giuliani. When Sid's own situation at the factory starts to feel untenable, she briefly takes up with another loose group of squatters from Manhattan intent on claiming an abandoned theater a few stops further into Williamsburg under the J train on Broadway. After only two weeks of doing what they can to fix up the impressive space and lock out the prostitutes and drug addicts (a move that at least a couple of them do seem to rightfully acknowledge is ideologically problematic, hypocritical even), it turns out that the edge of Bushwick isn't quite ready for prime time yet.Wakefield doesn't shy away from the looming gentrification that shadows her story and consumes New York City, San Francisco, and other metropolitan areas today.

Ever since the children of white flight began rejecting suburban malaise for the appeals of density, it has followed: first comes the fringe creative types, then comes the more well-off creative types, then comes the real money. Squatting certainly had a moral legitimacy in its positive use of derelict buildings, and though the dream might have been short-lived for many, at least it was lived for a time. Still, Wakefield occasionally teases at the writing on the wall with her (possibly) unwitting characters. As Sid recounts of walking in Williamsburg with her friend Raven in the summer:

The weekend was really hot, and I took Raven down to Kent Avenue where we climbed under the fence past the trash pile to the hidden, disintegrating pier. She spread her arms wide to encompass the city floating over the dark river.“This is so rad!” she cried. “In the city there'd be a gazillion yuppies walking their dogs here.”

Just you wait, Raven.

Stacy Wakefield published her first nonfiction book about squatting, the underground classic Not for Rent, in 1994. Her debut novel is The Sunshine Crust Baking Factory. Wakefield is cocreator of the photo/essay book Please Take Me Off the Guest List with Nick Zinner and Zachary Lipez. She grew up in the Pacific Northwest and lives in Brooklyn and the Catskills with her husband, musician Nick Forte.