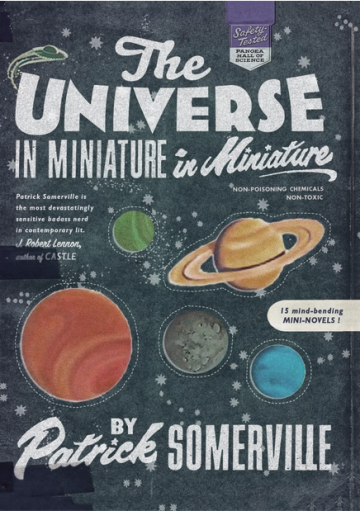

Review: THE UNIVERSE IN MINIATURE IN MINIATURE

Human beings have two systems for making sense of their universe, two ways of understanding the seemingly unfathomable pain and suffering and sorrow and even beauty of their lives. The first is art, and the second is science. In his exquisite collection of linked short stories, The Universe in Miniature in Miniature, author Patrick Somerville illustrates the appeal – and the shortcomings – of both approaches, and leaves the reader all the more astonished with the mystery that is existence.

The stories in The Universe in Miniature in Miniature orbit like planets around an event that sounds better suited for a two minute clip on the evening news: the stabbing of a recent college drop-out by a madman on the street. Yet this incident, as seen through the eyes of the boy's doctor (“Easy Love”), his parent (“The Mother”), the police officer on the scene (“The Cop”), the madman (“The Abacus”), the boy himself (“The Son”), and finally a telepathic bystander (“The Machine of Understanding Other People”), exerts surprising gravity each time it returns.

The boy's death, we come to understand, isn't just a personal tragedy – though it's that too – but a call for philosophical re-evaluation: an example of “news that's so crazy you decide you ain't gonna take it,” as the murdered kid's mother says. What do we do in the face of such realities? Where do we turn?

That's a question the characters in these stories answer with varying degrees of soul-searching, and wildly different results. In the title story, three students at the unaccredited School of Surrealist Thought and Design (SSTD, for short) are struggling with their “projects,” the only requirement for their graduation. “Our projects are whatever we want them to be,” the narrator Rose explains. “We have total freedom and I'm not sure anybody even looks at our projects when we're done.” SSTD serves only as a shield – and a thin one, at that – between them and the dizzying existential void. The characters constantly second-guess their own attempts to make meaning: “I condemn my own art as I make it...Is that okay?” Rose asks in conversation. Yet the subjects they tackle in that work are not so easily dismissed.

Rose's classmate Lucy is studying the collapse of a family after the son, a young man she used to love, suffers horrible brain damage in a freak accident. Another student, Dylan, is writing a novel about a group of scientists whose knowledge destroys the world, but which might also be the only thing capable of saving it. And in her own work, a series of sculptures of fathers and sons building miniature solar systems, Rose – like Somerville himself – seeks to reflect both the poignancy and the insignificance of human attempts to comprehend our vast universe. Another story, “The Wildlife Biologist,” examines science on its own terms. In the wake of her parents' separation, teenage narrator Courtney finds herself smitten with her biology teacher, not just because of his rebel persona, but because of the comforting clarity his worldview provides. When on the first day of class, he asks his students to come up with “the definition of life,” Courtney comments, “I noticed that he said ‘the' and not ‘a,' which was different than what most of the young teachers said about truth and definitions, no matter what the class. They liked to say ‘voices' and ‘readings' and ‘models' and ‘the situation of the observer.'” She falls in love with the possibility of truth, but finds herself sorely disappointed when she discovers her teacher's wisdom isn't enough to help him make sense of his own life, let alone life on earth.

Some of the characters here retreat from knowledge when it proves inadequate to help them function, though they still find a return to total naiveté impossible. In “No Sun,” a former addict finds hope for the first time only after the world stops spinning on its axis, plunging his hemisphere into darkness and cold. “What if we start spinning again?” he asks, adding a little later, “Why not go all-in for hope? Every time? What other arguments made sense? It had taken apocalypse for me to see it.” But his uncle, a physicist, is unable to embrace this: “It may start again,” he says. “But it won't make a difference... I mean that now, and forever, we won't know what to believe. Our knowledge has fallen apart.” The uncle's very ability to grasp what has happened makes it impossible for him to survive it.

The novella that concludes this collection synthesizes the artistic and scientific impulses into a single object: “The Machine of Understanding Other People,” which is also the piece's title. In this story, despondent alcoholic Tom Sanderson receives a strange inheritance: “a piece of technology that distilled the power of romantic poetry into a usable, portable device,” a helmet that allows the wearer to enter other people's minds. Invented in wartime as a weapon but never deployed, the contraption seems useless to Tom at first: “[W]hy do it at all? Why run around investigating the minds of other people? There was no goal, no endpoint.” Like truth, like beauty, the understanding the helmet provides isn't good for anything. And yet, as Tom starts to use the machine, he realizes that there's an intrinsic value to the experience. “It drew you in,” he thinks. “It freed you. It opened you up, this knowing other people... It was something good to understand another person, if not for a couple of minutes. He'd never really thought about it before. How there was something inherently good in that. And considering how few inherently good things Tom perceived in the world, he took note.” Human intellectual endeavor, human seeking, may be puny and limited when seen in the greater scheme. But to us as individuals, it has whatever value we choose to give it.Somerville is an author of extraordinary talents, and The Universe in Miniature in Miniature is that rare thing, a formally inventive and profound book of ideas that also manages to stir the emotions. Though the scale of each piece is small, it's hard to imagine a writer of larger ambitions.

Patrick Somerville is the author of the story collection Trouble and the novel The Cradle. He has taught creative writing and English at Cornell, Northwestern University, Auburn State Correctional Facility, and The Graham School in Chicago.

Patrick Somerville is the author of the story collection Trouble and the novel The Cradle. He has taught creative writing and English at Cornell, Northwestern University, Auburn State Correctional Facility, and The Graham School in Chicago.

Chandler Klang Smith's genre-bending novel The Sky Is Yours (Hogarth/Penguin RH, 2018) was listed as a best book of 2018 by The Wall Street Journal, New York Public Library, Locus, LitHub, Mental Floss, and NPR, which described it as "a wickedly satirical synthesis that underlines just how fractured our own realities can be during periods of fear, unrest, inequality and instability." Chandler has an MFA in creative writing from Columbia University. She has served twice as a juror for the Shirley Jackson Awards, worked in book publishing and as a ghostwriter, and currently teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College.

Chandler Klang Smith's genre-bending novel The Sky Is Yours (Hogarth/Penguin RH, 2018) was listed as a best book of 2018 by The Wall Street Journal, New York Public Library, Locus, LitHub, Mental Floss, and NPR, which described it as "a wickedly satirical synthesis that underlines just how fractured our own realities can be during periods of fear, unrest, inequality and instability." Chandler has an MFA in creative writing from Columbia University. She has served twice as a juror for the Shirley Jackson Awards, worked in book publishing and as a ghostwriter, and currently teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College.