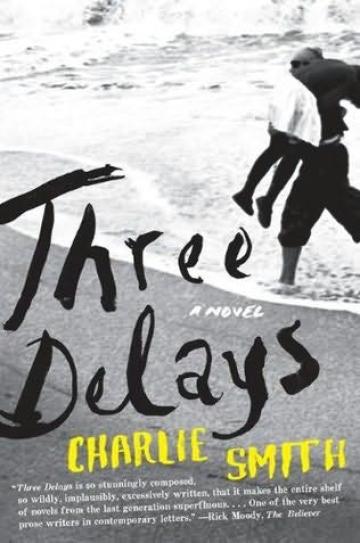

THREE DELAYS by Charlie Smith

Don't ask me about the three delays of Charlie Smith's new novel, Three Delays. Who or what's delayed, when, why – whether there are any delays at all – I couldn't tell you. This isn't a book that impresses with its structure or clarity, or wants to. The narrator explains:

What I wanted from drugs, and for that matter from life – and dreams – was for an accelerant to be applied, then something else added, embellishment. It's the topping that's the key, I told my friends, in life and drugs. The overtopping. I didn't want to just get there, I wanted to be spun wildly once I was there.

It's one of his calmer moments. I don't think I need to reassure you that he succeeds in spinning himself wildly. But when an ex-boy-preacher-turned-drug-addicted-poet tells his life story he will come up against one of the stranger paradoxes of the author-audience relationship: it usually isn't much fun to listen to someone talk about all the crazy things he did when he was on drugs.

The preacher-turned-poet's name is Billy Brent, and though his life is punctuated with pills and needles, he admits his drug of choice is Alice, whom he first glimpsed at age six while conducting a children's wedding ceremony in Miami. She's as perpetually frenzied as he is, and the novel opens several years after their tempestuous, abusive relationship in their late teens, when he's bumming around Europe, scouring for drugs, she's in Florida married to someone else, and both remain convinced they are meant for each other. “The miracle of my experience with Alice,” Billy tells us, “was that her street, the Alice street in the Alice town, never played out. And what a poignant, interesting street it was, saucy little street with its flags in the sycamores and its taffy shops, its abbattoir and munitions factory...”

Billy and Alice's penchants for exuberant experience and illegal substances propel them into a Hemingway-esque plot, or rather several Hemingway-esque plots in a row: in Venice Billy's mixed-up in a murder and wrongly imprisoned; back in Miami, he works as a reporter and saves Alice from her potentially homicidal second husband; desperate for cash, he and Alice join the crew of a smuggling ship, and it turns out badly; he begins to write poetry and fiction as he cares for Alice while she undergoes shock therapy; they separate, until Billy kidnaps her back and – but I won't go past the novel's first half.

It isn't that Billy and Alice's story is unbelievably eventful; their propensities would repeatedly imperil them. What's off-putting is that no matter how Billy writes about the anguish of loving a woman as volatile as Alice, or the sordidness of his other addictions, he remains enamored of how wild his and and Alice's experiences are. “You know,” he thinks, as they flee drug-dealers in Mexico:

all this is especially beautiful because if you saw us at this time you would not say look at that interesting couple, those swells, trekking in Old Mexico, you'd say oh look at those losers, or you'd say there but for fortune go I, or my my, or why don't they get jobs or what is this world coming to, or get away from me creeps, but you wouldn't say what a feat of artistry, of gallantry even, you wouldn't pick up on that at all probably, but that is what it is...

No one is going to expect sober analysis from Billy; but amidst all of his rhapsodizing, not even a clear picture of Alice emerges. There's only his insistence that loving her is ecstasy.This hyperbolic, lyrical style does produce vivid prose: beneath “spindly, neglected trees...the ungathered oranges were shriveled, apricot brown like eclipsed moons”; “the ocean was bright pale polished turquoise and untroubled by anything it had ever done.” And – perhaps because of all the bombast – the book's sporadic pauses can be very affecting, as when Billy spends a quiet evening with another woman:

She put her hand on my back and for a second the weight of it took me into a place where everything was strange. I didn't know who I was or where I was. Or who was touching me. The only life I ever believed in was the life with Alice, I knew this, and knew it had always been that way. And then the feeling or the knowledge of this, whatever it was, passed and I came back into the ordinary world we were in.

And then there's this to consider: I'm not sure whether to praise Smith's perseverance or my own, but near the end of this nearly four-hundred page book, all of my problems with it ceased to matter. Maybe such sustained intensity simply can't be ignored, maybe it's that characters so ardent are few in contemporary fiction, maybe if you listen to someone this passionate long enough you're inevitably drawn in – I'm not sure. But when, in the final pages, I sensed I would find out, definitively, whether Billy and Alice would stay together, or circumstances would drive them apart, I started to feel the despair they were starting to feel.I don't know why Billy and Alice got together, or why they stay together; I don't know what Billy sees in Alice; I don't know who Alice is. But I do know – with a certainty that's rare when regarding a work of fiction – that Billy loves her.

Charlie Smith is the author of six novels and seven books of poetry. Five of his works have been named New York Times Notable Books.