Parallel Play: Growing Up with Undiagnosed Asperger's

What does it mean when science gives pathological names to traits like, say, extreme introversion and social discomfort? Does it flatten their human meaning or offer a much-need identity and support groups for its sufferers? What about the essentialism of the label, be it stigmatization or pride? More importantly — what kind of life do you expect to read about when you consider the title of the memoir?

I'm not trying to pick a fight, I promise, but there is “a will to power in nomenclature” as the critical theorist Ihab Hassan might say. The naming of a disorder is troubling in the context of literary nonfiction — it casts a huge shadow over the narrative. I'm not sure what to make of it.

The absolute first thing to be said about the book, however, is that Tim Page's memoir reads like the biography of a reclusive rock star. Its pages teem with warm characters and hilarious, heartbreaking stories. At its heart the story is about otherness, and it explodes stereotypes of Aspies standing aloof from the full deluge of human drama. Page may be deeply uncomfortable in social situations, but this doesn't deprive his tale of warmth or human color — by contrast, it enhances its poignancy.

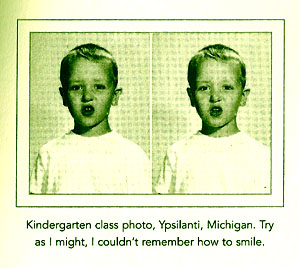

Like many characters in contemporary American letters (in graphic novels, especially), Tim Page endured his childhood as an idiot savant, a brilliant but mismatched kid. An enclosed kindergarten photo shows him grimacing for a yearbook photographer, straining for the appropriate expression (“try as I might, I couldn't remember how to smile”). As a preteen, he obsessed over classical music records and silent films and scorned the Hollywood “talkies” of his generation. By the age of twelve, he was a budding film director and the subject of a nationally acclaimed documentary, winning him an audience with the then-in-vogue Marshall McLuhan. The very same precocious traits of genius and “imperial intellectual arrogance” later found him stranded in his own head, “aching to be touched” as puberty sets in and his social impairment becomes clear.

Like many characters in contemporary American letters (in graphic novels, especially), Tim Page endured his childhood as an idiot savant, a brilliant but mismatched kid. An enclosed kindergarten photo shows him grimacing for a yearbook photographer, straining for the appropriate expression (“try as I might, I couldn't remember how to smile”). As a preteen, he obsessed over classical music records and silent films and scorned the Hollywood “talkies” of his generation. By the age of twelve, he was a budding film director and the subject of a nationally acclaimed documentary, winning him an audience with the then-in-vogue Marshall McLuhan. The very same precocious traits of genius and “imperial intellectual arrogance” later found him stranded in his own head, “aching to be touched” as puberty sets in and his social impairment becomes clear.

“It seemed like life was one big orgy that I was just managing to miss,” he mused sullenly. The scientific diagnosis, as it turns out, is Asperger's Syndrome — a milder autistic condition that makes David Mamets, Nietzsches and Ladyhawkes of some people, but more often leaves its sufferers privately broken. Tim Page is a little bit of both, though he admits to being one of the more fortunate Aspies.

He would later receive a Pulitzer Prize in music criticism, restore Dawn Powell to her rightful place in the American literary pantheon, and become close friends with such music luminaries as Philip Glass and Aaron Gould. He was not diagnosed until he was forty five.

In any case, the narrative is familiar here — the idea that genius can sprout as recompense for psychological misadjustment. We're reminded of Susan Sontag's solitary childhood spent memorizing encyclopedias as her family unraveled, of Van Gogh's mythic left ear, of Ruskin's unconsummated marriage and Newton's miserable bachelorhood. In general, we like to think of intellectuals as beautiful, charming losers. Or sometimes just plain losers.

It's for entirely different reasons that I find this book difficult to review. I share many of Page's eccentricities, especially in childhood — for one, I was (am?) similarly uncomfortable with myself. I've always had repetitive verbal tics, and a succession of geeky hobbies that I would devote to with what my parents call a "one-track mind." In kindergarten, I blew a year's worth of allowance money on a professional fishkeeper's tome of marine biology, which I quickly devoured and memorized. When I saw other kids grabbing at blue-ringed octopuses on Taipei's shorelines, I'd jarringly snort out [an approximate Chinese translation of] “DO! NOT! TOUCH! They have the... the worst neurotoxins of all cephalopods ever!” which frankly weirded the shit out of people. I was also a skilled draftsman but somehow never included people in my early doodles — something that disturbed my teachers so much that they implored me to populate my landscapes with a grandma or two (the only other artist who refused to draw people, I was told, was Hitler).

It's for entirely different reasons that I find this book difficult to review. I share many of Page's eccentricities, especially in childhood — for one, I was (am?) similarly uncomfortable with myself. I've always had repetitive verbal tics, and a succession of geeky hobbies that I would devote to with what my parents call a "one-track mind." In kindergarten, I blew a year's worth of allowance money on a professional fishkeeper's tome of marine biology, which I quickly devoured and memorized. When I saw other kids grabbing at blue-ringed octopuses on Taipei's shorelines, I'd jarringly snort out [an approximate Chinese translation of] “DO! NOT! TOUCH! They have the... the worst neurotoxins of all cephalopods ever!” which frankly weirded the shit out of people. I was also a skilled draftsman but somehow never included people in my early doodles — something that disturbed my teachers so much that they implored me to populate my landscapes with a grandma or two (the only other artist who refused to draw people, I was told, was Hitler).

Like Page, I found it impossible to look anyone in the eye, left many flies unzipped, and rejected birthday party invitations in a way that assured that I was never invited again. I mostly chalked that up to being a giant nerd, though, and and point is not whether I (or other hypochondriac readers) have the Syndrome or not. The point is that Page's plight is extremely sympathetic to those similarly inclined towards dwelling in their own minds.I also feel that — in the context of a literary memoir — the Asperger's label steps a little uneasily on (or around) literature's toes. Bookish loneliness is a time-honored American narrative; miscommunication and alienation, even more so. Asperger's is a relatively new scientific term. It's hard to trust one diagnosis to encapsulate the psychological isolation that has long been the scab, scourge and badge of honor for many incorrigible introverts. There are countless websites that ascribe autism to literary characters such as Sherlock Holmes and Frankenstein's monster, but that is neither fair to science nor art.

Thankfully, while the book's title promises something almost clinical, Page's memoir mostly acknowledges this prognosis obliquely and with much humor — he understands that the “Aspie” label may not be the biggest narrative meaning we derive from the work, though many will find consolation in it. And just as the condition lurked in the background of Page's adolescence, so does it lurk behind the memoir's more poignant anecdotes.

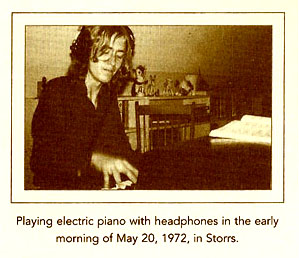

Page wrote this volume as an expansion on his well-received New Yorker article, and while the article (Chapter 1, incidentally) focused on the early-childhood manifestations of Asperger's Syndrome, I found myself most interested in his adolescent copings. Page mercifully came of age just as 60's eccentric chic reached its apotheosis. After a brief school year spent in Caracas, he returned to Connecticut determined to turn otherness into cutting-edge hipsterdom:

I didn't have the physical capacity to be a jock; my grades were too poor for me to fit in with the future Ivy Leaguers; I had none of the comfortable composure necessary to be a class leader — and in fact, I really wasn't interested in most of these people. But I might just fit in with the newly minted group of hippies — or “freaks.”

He goes further on to describe not wanting to be “classical-piano-film-nerd Timmy Page ever again but an intrepid explorer of inner space, a wise [Marx-reading] hipster.” And in this sense he mostly succeeds at reinventing himself. Besides the coincidence of the loathed H-word, and despite the fact that Page is describing high school here, does this not sound like the life trajectory of so many fragile new immigrants to Brooklyn — and in fact, all the awkward underdogs who have tried to reinvent themselves in American literature?

Insofar as the Syndrome explains Page's more solipsistic tendencies, it also amplifies a little-credited but also very adolescent male impulse — a sincere yearning for cosmic beauty. The maleness of Asperger's has been a sore frontier between science and gender politics (a Huffington Post article once asked if Asperger's couldn't just be explained as “TMB” — Typical Male Behavior), but it's hard not to see his tale as emblemic of a subset of the male adolescent experience. We all know people like the young Timmy Page, the idealist hiding behind the “snide know-it-all [record store] counterperson.” They were the profound geeks who sulked through adolescence thinking that the present social world really kind of sucks.

Yes, if he had grown up in the '00s, he might've been a Radiohead evangelist. But as the memoir makes clear, it's easy to forget that behind the wounded posture is often a painfully earnest desire for higher meaning. Even as a pre-teen, he found meaning behind collecting obscure classical records — they weren't just inert old junk, they were the shivers and longings of already-deceased humans, a means of staring down his own incomprehension of death (and there were many deaths in his life). As a teen, he experienced every friendship as a rare and improbable accident and grieved all the more for their passing. Say what you will about stratospheric ivory-tower daydreaming, but you'll feel its painful absence on an average night out in town around, say, Bleecker Street or the Lower East Side.

That is not to say that Parallel Play is all a somber paean to biologically-doomed loneliness. In the next sentence, Page could easily describe an acid trip gone awry (“Let me in! The sun is melting my eyeballs!” he remembers bellowing to his neighbor) or poke fun of his stint as botched graffiti bomber at a Venezuelan expatriate school. His friends led him on giddy brushes with 60s counterculture, debating the merits of LSD at the local scenester café and playing atonal music in hilariously unpopular bands. When he briefly dips into defenses of his musical preferences — say, the largely forgotten ‘60s band Procol Harum or later Beach Boys — it's easy to see why he received a Pulitzer Prize in music criticism. He meanders, expounds, but is always gentle in his erudition. At its best, the book reads like a particularly good and intimate bar conversation.And for all his professed alien-ness, Page is less socially avoidant than he makes himself out to be. He looks back warmly on a life spent with a small but loyal cadre of maverick friends. They drift in and out of his life, many of them die before their time, and all the while he misses them terribly. As with his choice in hobbies, Page either ignores people completely or — with the few he lets in — holds them very close to his heart. Page is no Sartre here; hell is not other people, but certain types of other people:

Some people make me crazy — pushing their faces into mine, finishing my sentences, repeatedly calling my attention to things that don't interest me and that I don't care to know about — and I can take these distractions for only a short time before I become unhappy and, on occasion, downright rude. In such circumstances, I feel physically threatened, as though I were trapped in an astronaut suit and somebody had released a hornet into the helmet.

For someone who describes empathy as a “hard-won” trait and wonders if he's a mammal at all, Page is a strikingly warm writer. And in this way, the epilogue is his most heartbreaking chapter. He journeys through continents, devours lifestyles and eras, succeeds as a music critic, finds close friends, marries, fathers two sons, divorces, and experiences an all-consuming love in a way he feared he never would.

The end of the memoir, however, finds him alone in a house full of books, as many of our relatives, friends and parents do in the latter half of their lives. “I have reached the point where every parting begins to feel permanent,” he writes. I'm forced to recall that old Harold Bloom coda — that “literature is otherness, and thus alleviates loneliness.” As a reader of this memoir, I find this to be true.

But for Page, scientific diagnosis offers a sort of comfort that literature and art has only partially fulfilled. For Page, being diagnosed was a profound relief. "I was forty-five years old when I learned I wasn't alone." A poignant observation. Perhaps the troublesome little scientific word exists for a better reason than we'd admit.