I'm Into Leather

The sign for Chief's Café in Pittsburgh was a neon fireman's hat and hose. Someone threw a rock through the right side of the sign and smashed it up, but it still glowed and buzzed like an electric snake. I guessed the owner was a fire chief. I guessed this was the kind of place someone who lived for emergencies built. I hung out at Chief's because I was 26 and trying to be a poet and beer at Chief's was cheap and I liked to drink when I had poet-emergencies over heartbreaks and line-breaks and bitchy form-poets who counted syllables by whacking pencils against their teeth. Chief's was not a formal-poet place. Chief's was a barfly place where the bartender doled out bags of barbecue pork rinds and wore a cowboy hat that looked like it had just been punched. I was in graduate school for poetry.

One night, after a particularly bad workshop, and a nice round of pity-partying myself, I called my friend Felix and he agreed to meet me at Chief's if I promised to pay for the beer. “As many as it takes,” he said when I picked him up at his apartment in Homestead, and I said, “At least.”

Felix was a poet-slash-performance artist. He performed his poems on MTV and once off-Broadway in the nude. Sometimes, when he had money, he and some friends rode around in a van that looked like they beat it with hammers. “We bring poetry to the people,” Felix said, and he sounded like Whitman, though the van thing was probably more like banging on a can in the subway for beer money. Felix called himself a street poet. In graduate school, I was a teaching assistant. Before this, not long before this, I hadn't known they gave people degrees to write poems. “That's just fucked up,” Felix said about universities and poetry. My family agreed. “At least you'll be able to write something on those signs you'll be holding up,” my cousin Jeff said. Jeff had a little Hitler mustache. His face was a fist I wanted to bump with a truck. “Will Rhyme for Food,” Jeff said, and made like he was putting it on a t-shirt.

I hated him. I hated my poetry professor, too, which was what this was all about. “She says my poems lack emotion and meaning,” I told Felix. I faked a British accent and pretended to peer over bifocals, even though the professor in question was from Las Vegas and did not wear glasses and she said her perfect vision was a metaphor for the poet's gaze.

“One must see well to truly see,” she said, like it was another thing to put on a t-shirt, this time a very expensive one.

***

When I first came to graduate school, I showed up in a puffy-paint sweatshirt I bought in Key West. Like all things Key West–key chains, shot glasses, assless chaps–the sweatshirt had a picture of Hemingway on it. I thought Hemingway would make me look literary. I thought Hemingway would help me make friends. I was new and scared but I'd read every book Hemingway published, which meant I'd read enough Hemingway to know Hemingway would hate having his head on puffy-paint sweatshirts. Still, I figured reading that much Hemingway should count for something.

“Cute shirt,” a Ph.D. student I didn't know said. I was going to say thank you when I realized she was being ironic. Irony is the language of graduate school. I was just learning to tune my ears and brain to it. Years before, I'd have called Ph.D. a bitch. Years later, I'll call her snarky. In this moment, I was supposed to call her a Deconstructionist while quoting French theorists whose names sounded like farts. Ph.D. pointed at my chest, then brought her finger up fast to flick my nose. I looked down at my shirt, how big it was, the rolls of blue cotton sagging around my waist and breasts, the toxic smell wafting up from Hemingway's beard.

“Just so you know,” Ph.D. said. “Hemingway was a racist misogynist homophobic asshole and the patriarchy is d-e-a-d DEAD.” Then she spun on her pink combat boots and stomped off, thrift-store hippie skirt wafting behind like incense.

***

I used to think I would fit in among my own people – writer people, book people – and that things would be different than they were back home with my cousin Jeff. I used to think books and reading made people kinder, gentler. I used to think books made people better, that books would make me better, but there's only so much books can do.

***

Back at Chief's, Felix and I sat at the bar, a stack of ones and some quarters in front of me, exact change plus tips. Felix rubbed his nose, then swirled a finger in his beer, the salt from his skin taking the head down to nothing. “I mean if my poems lack both meaning and emotion, head and heart, what do they have?” I asked Felix, over and over, until his eyes went limp, until he started playing with his dreads. He pulled them to his nose, one after another, like he was checking to see if he smelled like smoke because everything in Chief's smelled like smoke, down to the smeared beer glasses and fake wood paneling. The guy next to us, who smelled like smoke and looked like a chicken cutlet, his skin breaded in sand and dirt and peanut oil, said “Poets.” He said, “Fuck.” He said, “I should write a book.” He said, “You think you know some shit? I know some shit.” The floor beneath him was covered with the fluff and sawdust he'd picked out of his slashed red vinyl seat. Most of the seats in Chiefs were slashed and I thought maybe everybody in there had a knife but me. “I know this one guy. He brought a bowie knife to one of those workshops once,” Felix said. “He didn't say anything, just plopped the knife down, wham, like that on the table and gave it a little twirl, like he was spinning a bottle, like he was waiting to be kissed. Nobody said anything to him after that.”

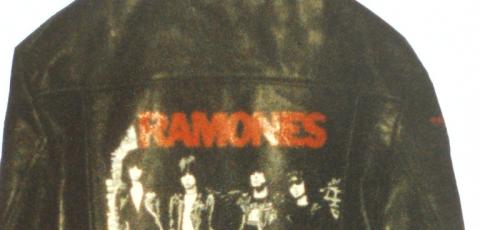

“I don't think that would work for me,” I said, but I thought about Ralph's Army Surplus, where I bought my black turtlenecks. I thought about Ralph's collection of knives behind glass and the Semper Fidelis flag hung over the counter and the retired Marine clerk who liked to talk about how he used to train grunts in Vietnam by hitting them over the heads with two-by-fours. “What you need,” Felix said, “is a way to get people to stop fucking with you. You need a front.” Then he took off his leather jacket and handed it over. “I've always loved the Ramones,” I said and pumped my fist. Felix said, “Fuck the Ramones. Put that on. It's yours. At least wear it to that workshop. You'll look tough if you lose that secretary hair.” I ran a hand through the tangles of my blonde perm, which up until that minute I'd thought was o.k.—wild even. I said, “Are you serious?” About the jacket, I said, “It's too much,” even though I was already putting it on, even though it felt instantly right, even though the leather was a little squeaky and the studs on the collar a little big and the whole thing smelled like it had been through a fire, a fire that maybe Felix set because Felix was violent and troubled in ways I refused to think about.

***

Felix and I wanted to be deep, believed we were deep. Twenty years later, I realize I no longer care about deep, can no longer define deep, could give a shit about deep. Twenty years later I know deep never existed. I have a husband now, and two kids, and four books. I know exactly who I am at most moments and the people I love remind me the other times. It would take me years—maybe until this second—to realize how little I knew about Felix. The stories he told bounced off my permed hair and my stupid poems and the leather jacket and echoed like every other story I heard, a little sadder, maybe, but still a story, another line from another poet that was probably true but maybe not. Felix's dad beat him, I think. I know his mom wasn't around. He wanted to go on tour with Lollapalooza. He wanted to meet Nirvana. He was friends with Ani Difranco. He was diabetic. He liked cats but was allergic, so he left milk out for strays. One time, stoned at my apartment, he jacked off in the bathroom and wiped it on my roommate's monogrammed towels. I thought he was gross, like a person who doesn't shower, not like a rapist. So I didn't invite him to our apartment. But I still met him at bars. Gross was fine for bars. One time he asked me to hold a big Ziploc bag of weed in our freezer for him. I didn't do it, even though he said if I did I could take whatever I wanted. I don't know why I didn't do it any more than I understood why I did the things I did. Also, I really liked pot.

“Take whatever you want,” he said. “It doesn't matter how much you take.”

When I said sorry, no, Felix stored his weed somewhere else and gave me free joints anyway and my life went along easy like that. So Felix was as shallow as me. He was worse. I liked worse. I could take from someone who was worse. I could take from someone who was cool. I get confused, remembering how stupid I was. Felix never called me on how much I took. His weed. His time. His jacket. His friendship. That's not really friendship. Taking without giving is a shitty thing to do, but I kept on. Felix's giving without taking was something else -- an emptying out, maybe. About the jacket, I said, “Thank you. Holy shit.” I caught a glimpse of myself in the metal bar posts. I caught a glimpse in the greasy bar mirror. I squinted and turned and felt, maybe for the first time, inexplicably myself, even if I was the punchline my cousin Jeff had been hoping for all those years. I was pushing 30 and dressed like The Fonz. I wrote terrible poems, but I wanted to write better ones. As a writer, I believed form followed content. As a person, I was the other way around. “Build it and they will come,” somebody told Kevin Costner in that stupid movie “Field of Dreams.” I was building myself so the life I wanted would come. Felix was, I think, disassembling, though I was too lost in myself to notice.

***

“Thank you,” I said again to Felix, like he'd given me a kidney. He clicked his tongue against his teeth. He held his hand out to say stop. He looked almost vulnerable in his black t-shirt and jeans, like without his jacket he was mortal, just blood and skin. Felix said, “It's nothing.” He said, “Beer me.”

***

A few weeks after Felix gave me the jacket, I woke up with a Carlo Rossi hangover, a bad case of whiplash, and a bass player named Bix in bed beside me. Bix was naked and sprawled like Jesus on the cross, arms out, feet together in a twist. I was shoved to the edge of the bed, bare mattress against my cheek. I was wearing Bix's Nirvana t-shirt. There were brown crumbs all over the sheets and in Bix's scraggly chest hair. I had a vague memory of Bix, already drunk and stoned, slipping a tab of cartoon-Santa acid on his tongue, then making gingerbread from a box and feeding it to me with his fingers. The whiplash, I figured, was from the slam-dancing I'd done the night before, when Bix's band played at The Electric Banana and did a rocking cover of “Kung Fu Fighting.”

Bix's hair was splayed over two pillows. By the time he woke up, it was well past noon, which meant he was late and going to have to explain to his live-in girlfriend where he'd been. Bix had rock-star hair. Bix loved his rock-star hair. I think Bix's rock-star hair was the only thing I liked about him, too, but stress made Bix's hair fall out in clumps. “I have a condition,” he said, in the same way an 80-year-old man might talk about his goiter. Bix creaked out of bed, tenderly rolled his hair into a Rasta cap without combing it, then scooped the one remaining hunk of gingerbread out of the pan he'd stashed under the bed. Explaining to his live-in girlfriend where he'd been would be stressful, so after Bix left, I would have to vacuum up the hairballs that made a ghost-town tumbleweed path from my bed to the door. On his way out, Bix said in his swollen, phlegm-throated romantic way, “Let's hang out later.”

I'd like to say this is the moment when I started to re-evaluate my life. Instead, I plugged in the vacuum cleaner and got to work. I ran the vacuum back and forth until Bix's hair jammed the motor and I smelled burning.

***

I met Bix and guys like him through my best friend, Sasha. Bix was not Sasha's fault. Sasha did not approve of my taste in men. They were simply a by-product of the world she and I inhabited, full of artists and Bohemians and misfits who worked hard to be misfits and, of course, douchebags. “There are some sounds only dogs can hear,” Bix said when he was philosophically stoned, a metaphor for himself and other artists too deep to be understood by the average human. Sasha smoked Salem Slim Lights and twirled them movie-star-style between tiny red-tipped fingers. She read Tarot cards. She knew her way around liquid black eyeliner. She drank too much and wore low-rise jeans and lacy black bra-tops and she was wonderful. She was also a painter, but her boyfriend Ed headed up the band Bix was in. The band was called The Frampton Brothers, and Ed, a genetic splice of Peter Frampton and Kenny G., was the perfect front man. These days, Sasha had given up on painting, mostly because Ed didn't like the paintings she'd done of past boyfriends. Ed kept Sasha busy designing his CD covers and band posters instead. “The woman's got skills,” Ed said. Sasha was happy to help out. Still, I worried about her beautiful paintings wrapped up in garbage bags and hidden behind her couch. She and I often blew all our laundry quarters playing the Ramones on a jukebox in Jack's bar and talked about this. Sasha had plans – to get a better job, then a nicer apartment, one where she could have a studio just big enough for her easel and paints, not a guitar or amp in sight. “This is just for now,” she said. And I said, “You're an artist. You have to paint. You have to be true to who you are.”

I was a hypocrite, of course. I never talked to my musician boyfriends about writing. I played a good groupie, leather jacket and all. I played a good writer, sidled up to the bar at Chief's, but I'd written only one poem in the last three weeks. I'd written it over and over. I'd gone to nine rock shows instead. I stood in the dark and pretended to smoke and leaned in my black clothes against black painted walls and willed myself to disappear. Semper fidelis, the old Marine at Ralph's would say, then spit.

***

Even though I wished things could be different for Sasha, I did like Ed's band. I understood why their single, “Dwarf Bowling,” was a hit in both Japan and Germany. This may be why I went along for the seven-hour drive to Hoboken, New Jersey, for the band's biggest CD-release party ever. This party marked the launch of “Bonograph: Sonny Gets His Share,” a compilation album that featured hip bands covering Sonny Bono's greatest hits like “Bang Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down)” and “Pammie's on a Bummer.” The whole thing was Ed's idea. It featured REM's touring guitarist Peter Holsapple, the Flat Duo Jets, and Ed's band. The project had been featured on MTV and CNN. It made People magazine. “It's going to devastate them,” Ed said, and he meant critics. He meant “Bonograph” was going to be huge. And so Sasha and I loaded up her paneled station wagon with plastic cups and screw-top wine to toast what we were certain would be a gateway to superstardom. “Finally all this will be worth it,” Sasha said, and waved a Salem Slim Light around like a wand, like she was illuminating every dark corner of her life by showing the interior of this 1970s sit-com car she'd inherited from her parents and which now smelled like beer and sweat and feet and had been stolen once, but then found, abandoned somewhere in the Hill District. The thieves had taken some of Ed's equipment -- amplifiers etc. -- and left behind an empty can of peas. “What kind of person eats cold peas out of a can?” Sasha wanted to know, as if this could explain everything.

***

“Pipe dreams”—my cousin Jeff's phrase for when people tried to imagine lives other than the ones they were born into. When he said it, I imagined puffs of smoke, the hookah-loving caterpillar in “Alice in Wonderland” perched on the mushroom that could make Alice grow or shrink, depending. “Who are you?” the caterpillar wanted to know. “Who are you?”

Sasha and I had pipe dreams. They were as follows: we would make it out of Pittsburgh and get cars that wouldn't break down. I'd write, she'd paint, Ed would go on playing his music, Bix would go into rehab, I'd find a nice semi-drug-free guy with hair that stayed attached to his head, and we'd all move to New York, hang out in cafes, and be happy, the end. “Here's to better things,” Sasha said, a sappy song-lyric toast. She cracked open our gallon of Carlo Rossi. We lied down in the back of the station wagon, and drank our way to Maxwell's, a nightclub smack in the middle of Frank Sinatra's old neighborhood. “Whatever gets you through, baby,” Sinatra used to say.

***

When we got to Maxwell's, many “Bonograph” stars, including REM's Holsapple, were already inside, and rumors were static-ing through the crowd that scouts from major labels were there, too. The air crackled with feedback and possibility. It was probably very exciting, but Sasha and I were already drunk.

Once inside the club, we commandeered two bar stools, an ashtray, and a basket of peanuts. We didn't move except for the occasional bathroom run. At one point, a man with a ragged Beatles haircut and nice eyes leaned between us and said, “You two are so serious. What are you talking about? Smile, already!”I have always hated people who tell me to smile. It's pushy, and an order is a horrible pickup line, but this man seemed kind. Besides, he had a Polaroid camera. It's impossible to resist a Polaroid camera. So Sasha and I leaned together, both of us in our leather jackets, and played it up. Sasha wore her biker hat. My blonde secretary hair was now cut short and slicked back. “Cock your hat,” Sinatra used to say. “Angles are attitudes,” and we tried to look cool, tough, pursing our red lips and mugging for the camera here in Sinatra's hometown, but we couldn't hold out. Soon we beamed and the camera snapped and there we were, full of sweet cheap wine and joy in that dark and beautiful place. We didn't know then that the guy with the camera was famous. We'd learn later, from the bartender, that the man was Peter Buck from REM. Years later, Ed would say we're crazy, that it was probably Holsapple, but I've looked at pictures of Peter Buck and this is the man I remember. Back at Maxwell's, Peter Buck told us he was going down the block for a slice. He asked if we were hungry, if we wanted him to bring something back. He seemed like a neighborhood guy, about as far from a rock star as you could get.

***

What did we know?“If the desire for the light is strong enough, the desire itself creates the light.” Simone Weil said that. Simone Weil died at 34. She joined the French Resistance and starved herself out of compassion for soldiers who were dying of hunger. Albert Camus called her the one great spirit of his time. She was, more or less, a saint.Sasha and I did not want to be saints. We didn't think about compassion, although it would have done us good to do so. We wanted to be artists and decent people. We wanted to be beautiful and good and wise, but we weren't anything, not yet. We didn't know anything, not yet.

***

We didn't know, for instance, I'd be the one to end up in New York. I'd be a flight attendant. It would not be glamorous. I would not become a writer in New York. It would take love and family and coming back home to Pittsburgh to do that. We didn't know nice Peter Buck would one day be arrested for getting drunk on an airplane and throwing yogurt at flight attendants like me. We didn't know Ed would go to work for a newspaper and be known as a music critic more than a musician. We didn't know Sasha would never get back to painting, but would marry Ed, move to the desert, and stockpile paints on the sly. We could have guessed Bix would be a balding rehab dropout and simply disappear.

***

Felix ended up in Europe, where he was sure he could become a famous performance poet. “They take art seriously over there,” he'd tell me before he left. “Their poets are like fucking rock stars.” Felix emptied all the way out, then tried to kill someone, a blonde woman with secretary hair and a sweet smile who was trying to be a poet, too. I was shallow and didn't try to kill anyone. Felix was shallow, so I assumed he wouldn't try to kill anyone. I didn't know he'd use a knife. I didn't know the woman would live. I didn't know Felix would kill himself instead, overdosing on insulin. He'd call me first, collect.

Years later I wouldn't remember anything he said.