KGB Interview: Iris Smyles

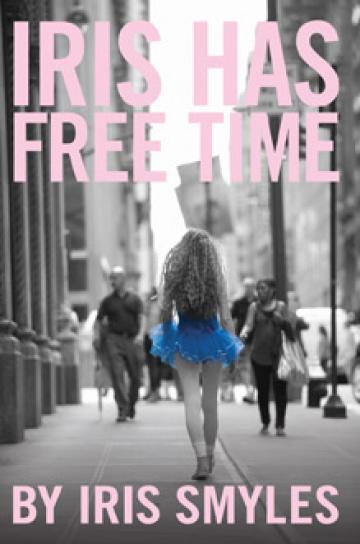

One of my favorite recent reads was Iris Has Free Time, by Iris Smyles. Eclectic, funny, fast-paced and also reflective, there was something on every page I liked and found memorable. I am not alone in my excitement, as many reviewers have chimed in with praise, including The Rumpus, which said the novel's style "is reminiscent of a modern Joyce, a Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman." With that comparison as a launching point, here is my interview with this talented, rising author.

Iris Has Free Time has the immediacy of a memoir, the artistic reach of literary fiction, but, somehow, you are able to meld these two genres seamlessly into an imaginative, funny and wise novel. How were you able to find and sustain such a distinctive ‘voice' to tell this story?

I'd describe the voice as a combination of Dante, Proust and Anita Loos.The book might best be classified as autobiographical fiction. I recast some real events and real people within a fictional narrative. I tried where I could to use real names of institutions and/or people and purposefully confuse the line between fiction and non-fiction in an overt allusion to Dante's The Divine Comedy on which this novel is based. The Divine Comedy is autobiography, history, allegory, and fiction at once. The novel's other model is Proust's In Search of Lost Time, on which my title, Iris Has Free Time riffs. Proust's novel is a roman a clef with Proust himself doubling as narrator and main character. Proust, like Iris, wants to be a writer. Meditations on memory and time are fundamental to Iris Has Free Time, though I approach these themes in my own way.

I play with time a lot in my novel—time moves jaggedly, it lurches ahead, there are flashbacks, and some episodes are told in present tense in order to maintain the sense of blindness that comes with real life, with youth, when you don't know at all what will happen next. In writing about youth, evoking the sense of not knowing, of being lost, was paramount.

In IHFT, the point of view moves forward in a continuous present, but within that, Iris, tells stories that look back and ahead. The stories she tells about her past change as she matures. And so you see her grow up not by incident but through her evolving responses to past and present experience. This includes the little lies she tells herself, maybe unconsciously, the foolish ideas of a callow youth, and the overhaul of some of those notions in pursuit of wisdom over quick wit. Iris changes. She grows up. And her growth is reflected in her changing voice, and her willingness eventually to acknowledge her mistakes.

The person speaking to the reader on the first and last page is not exactly the same person; ten years pass between them. It was important that the Iris in the first chapters not be burdened by the hindsight of the person she grows into, because that betrays the truth of how we grow up. None of us knows what will happen next or what lessons we'll learn until we learn them. Being young is a guessing game. Some people are lucky and choose well right away. Others proceed down many a blind alley. IHFT is in many ways a chronicle of mistakes.

I broke the novel into self-contained episodes, almost short stories, because in your twenties life is sort of like that. It's this salad of little stories—jobs that lead nowhere, relationships that end, friendships that you thought would last forever that break—all the episodes of life don't form a perfect forward moving narrative, but somehow, through them, you move forward never the less. I wanted to capture that and so I resisted a conventional plot arc. The narrative thread of Iris Has Free Time is not driven by event but experience and reflection.

I wanted more than anything to show what it feels like to be young, to empathize and celebrate that. The pretend arrogance of youth when you're actually terrified. When you don't know very much and so try to gamble on hunches. There's this pressure to be fully formed. To know what you're doing. To live with confidence. But often you choose wrong, and how you move on from those choices is what really defines you. When we're kids we have our parents, our teachers, the community to guide us. And as adults, later on in our thirties maybe, we've figured a few things out and our lives are less tumultuous. One's twenties, however, are a crazy lawless time of experimentation. The training wheels come off. You're left to set up a life for yourself. Where do you begin? How do you proceed? It's a challenging, exciting, and devastating time. And I wanted to capture that joy and sadness and fear. So much is at stake.

Diane Keaton wrote a great review for Iris Has Free Time. This interested me because I see Iris, the character in your novel, as a modernized version of Annie Hall, the iconic character Ms. Keaton played in the Woody Allen movie of the same name. The movie had a great influence on women, including fashion. What are some of things you hope women readers will learn from your novel that they can impart into their own lives?

I didn't write this novel with women in mind exactly, so I don't know if I have any lessons exclusive to them. Iris Has Free Time is less about being a young woman that it is about just being young. I tried to evoke what it means to be young which is I think very much encapsulate by one's relationship to time. There is a feeling when you're young that you have forever, that time is a substance you're rich with, that comes in endless supply. You're an aristocrat, spending time without care. Young people hang out, killing time without worry, because it hasn't occurred to them yet, that it's in limited supply.

The notion of “free time” is an illusion of youth, which is partly what my title refers to. Adults know they're on a budget. While the young wake up one day and realize with a start how much they've spent, that there's only so much time left. There's a crisis there. Dante's comedy begins with a midlife crisis; Iris's begins with a quarter life one and concludes where Dante starts, at another turning point. It's this changing relationship to time and coming to terms with it that marks one's entry into adulthood, I think. It's a loss of innocence. On the same day that Adam and Eve covered themselves with fig leaves, they probably noticed for the first time that it was getting late. They donned watches.

I hope young readers might take comfort in Iris's story. One of the worst things about being in my early twenties, I remember, was feeling like I was completely alone in my struggle, that everyone else had it all figured out. I spent a lot of time in bookstores searching for a novel that would give me insight into what I was going through or at least some feeling of understanding. I never found it, so wanted to write it. I like to think of some recent college grad engaged in a similar search coming upon my book. It won't spare them their mistakes though because mistakes are necessary. I wonder, with that, if the book will really resonate with them in the way it would for an older reader who's already come out the other side.

My ideal reader is an older one, for memory and time figure heavily. While the book is told in present tense, it is more accurately about nostalgia, lost time, regret, mistakes made and how to correct them. While page one depicts a comically arrogant young woman, the book is much more a lesson in humility.

Explain your writing process during Iris Has Free Time - the ups and downs and all arounds.

The structure really evolved. I wrote and rewrote and wrote new chapters to fill in gaps between old chapters, which I then threw out. It took me four years to write the book and my first draft was over 700 pages. An agent who loved the book told me no book could sell a book of that length. In a fit of perversity, I planned to make it even longer by adding appendices. I told the agent I wanted to add the entire cetology chapter from Moby Dick (which is in open domain, so I could). It was a big decision—would I edit it further or try to publish it as is. The question I was asking then was not whether it would sell, but whether it had really reached its ideal shape. I wanted it to meander, which was the agent's primary critique.

I kept working. And I realized that by editing and rearranging and compressing, the narrative showed better. Once I started cutting, I found more places to cut. It was hard because the chapters I was cutting were good; some were favorites. I had to look at the book as a whole though and be ruthless, cutting anything that lacked forward momentum. Since I was not relying on plot to move the story forward, I wanted to make sure it didn't stall or stay too long in once place. I wanted each chapter to tumble into the next. My goal was to write a plotless, voice driven, thematic page-turner. How do you earn the reader's attention? How do you keep it? However serious, I decided, it needed first to be fun. Because it's a first person narrator with whom the reader is engaging, I applied to the narrative the rules of dating. Don't overshare on the first date, in the first pages. Don't get too serious too quickly. The first date should be fun. Let the crying, the confessions, the back-story come later.

One last editing lens was to cut the commentary and let the action—by action I include Iris's thought processes—stand alone. I cut any and all lines in which the author's perspective intruded upon the narrator's. Because I know better than Iris, it's tempting to filter the narrative through mature disclaimers of Iris's sillier thoughts and actions, to announce to the reader, hey, I get it. But I think the best writers don't explain, they arrange and leave the rest to the reader.

What's next for Iris?

Do you mean me or do you mean “Iris”? Is this a trick question? I'm working on a spin-off book called Dating Tips for the Unemployed. It's Iris's collected columns. A fictional non-fiction book of humorous essays about one's early twenties—trying to find love, trying to find a job, and trying to find yourself. That's next, and then there are other Iris books I have planned, though after this one, I will take a break from her for a while. Before this book, my stories were rather fantastical, and I'm eager to revisit those worlds again.

Iris Smyles' writing has appeared in The Atlantic, BOMB, Nerve, McSweenys.net, The Observer, Guernica, New York Press, New York Post, and various anthologies. A former humor columnist for Splice Today, she edited the 2010 humor collection, The Capricious Critic. Her stories and essays have received The Adria Schwarts Fiction Award, The Geraldine Griffin Moore Short Story Award, and The Lippman Prize. Iris Has Free Time is her first novel. She lives in New York and Greece. Visit her at www.irishasfreetime.com. And check out these videos (cut and paste in browser): At Home With Iris Smyles - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-o9_KZ0tTpc Iris Has Free Time - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GsU31yxkFL0