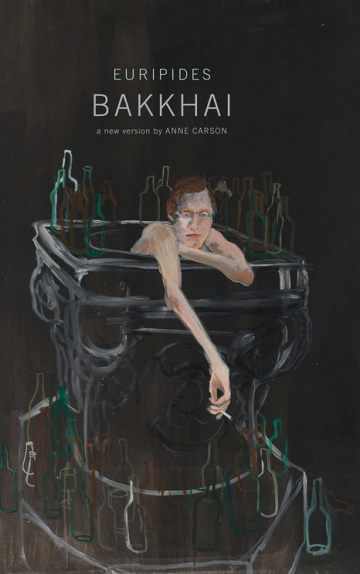

Bakkhai by Euripides

The protagonists of Euripides’ Bakkhai (New Directions, Dec 2017) are a new god and a cross-dressing conservative. Dionysos has just arrived from the east; though Anne Carson is quick to remind us in her new translation that his presence in Mycenaean tablets dates all the way back to the 12th century BC. This is not surprising. Dionysos is a perpetual stranger, and his religion a constant other. He is nicknamed Bromios (or “boisterous”), after his birth from Zeus’ thunderbolt, which killed his mother Semele and caused the god of gods, his father, to sew Dionysos into his thigh. From this “masculine womb” he is born again, which earns him his second nickname: “twice-born.” He stings the women of Thebes into madness with his thyrsos: a wand of giant fennel topped with a pinecone. He drives them into the mountains where they worship him with wild dances, ritual hunts, sexual escapades, and feasts on raw flesh and wine.

Pentheus, the young and hotheaded new ruler of Thebes, thinks this is all giving his town a bad name, so he imprisons the god’s followers—the Bakkhai, including his mother Agave. But the god liberates them. As is true for most radical conservatives, Pentheus’ fury and intolerance are mixed with irrepressible obsession. Dionysos, who has put on human form as a swoony, longhaired religious leader with “bedroom eyes” and “cheeks like wine” (Pentheus’ own words) is all too aware of this. He convinces Pentheus to dress up as a woman so that he may spy on the Bakkhai without being seen—thus quenching the young man’s curiosity and luring him inexorably into Dionysos’ followers’ claws. Agave sees Pentheus hiding in a tree, and in a fit of Bakkhic madness takes him for a young lion, slaying her son with the help of her maenads. The play ends with Kadmos, her father and the founder of Thebes, revealing to her the nature of her crime, which results in the family going into exile: each member cast out alone.

Anne Carson’s translation is all one would expect of her work: modern, frisky, precise, dense, completely original, and absolutely devastating. As in her other versions of Euripides and Sophocles (like Grief Lesson, Electra, and Antigone) Carson’s line breaks turn the play into a poetry at turns lush and riotous, at others glibly deadpan and ironic. The latter applies in both the dramatic and contemporary senses. At the hands of Carson, it’s a linguistic treat on every level: from Bakkhai’s cascading choruses, to the cast of characters’ rhetorical spars, to the final elegies spoken by Kadmos and Agave that leave one with a sense of raw and irresolvable trauma. Raw indeed on the level of character and drama, but air-tight as crystal in Carson’s economical verse. The result might remind us of what Nietzsche felt only Greek Tragedy could do: fuse the Apollonian and the Dionysian completely. But the play teaches us—and this might be its central lesson—that the Dionysian itself requires a balance of impulses.

The play is surprisingly fresh in its affirmative depiction of women’s spiritual, moral, and sexual freedom—in equal measure, it’s condemnatory of intolerant men. In the order of Bakkhai, the fury of a conservative cannot outlive his hidden fixations. A man of closeted compulsion, who subjects women to the duality of his voyeurism (desire and disgust) before he plans to destroy them for good, will suffer a horrible fate. The logic of Dionysos, in which these impulses must resolve themselves into consummation and release, will not allow this kind of stubborn and compartmentalized approach. The play’s Freudianism avails itself not only in repressed desires, but also ideological vision: the clash here is on the order of collective as well as personal fantasy, and is as frightening as it is fatalistic. And not too distant from the destructive results of our current politics.

Dionysos is no easy god to pin down. Carson associates him in her translator’s note (also a poem) with beginnings: “[he is] your first sip of wine / from a really good bottle. / Opening page // of a crime novel.” Tiresias, that blind prophet and traveler between sexes, summarizes him like no one else can: Dionysos is the “wet element”—“cool forgetting of the hot pains of day”—as well as “that flash across the peaks of Delphi / tossing like a great wild spark from crag to crag.” He fertilizes and sates by giving us drink and the knowledge to press grapes, and he brings forth visions and voluptuous pursuits, alongside the deep trances of terror and sleep. Tiresias instructs Pentheus to “pour his wine, dance his dances, say yes.” But Pentheus cannot be brought to yield, because he knows too well that in the case of Dionysos—who favors women—the patriarchy is at stake. He is unable to conceive for a moment that his mother Agave and her sisters, who are after all his “inferiors,” might know something that he doesn’t. His plans for the Bakkhai, who’ve taken up cymbals and drums, is to “sell [them] into slavery or put [them] to work at our looms.” And when it comes to Dionysos’ popularity abroad, he has few words: “foreigners all lack sense, compared to Greeks.” His prudish, belligerent, deeply misogynistic, and overtly xenophobic demeanor might remind us of Trump. As might his simpleminded diction: “This Bakkhic insanity is catching like wildfire. / What a disgrace! … we’re going to make war on [them].” Except, of course, Pentheus has the charm of being in his late teens or twenties, still somewhat malleable, and willing therefore to play dress-up for his basic instincts.

Dionysos is Pentheus’ proper foil: composed, quietly determined, patient, and sharp-witted. His response to Pentheus’ qualm with strangers is that “there’s more than one kind of sense.” When Pentheus sends guards to arrest him, Dionysos exclaims, “Okay, tie me up!” and after he escapes, he relates to the Bakkhai: “Just between you and me, / I had a bit of fun with him and his ropes.” However, after Pentheus crosses him twice, the dovish demeanor is revealed to be a mere externality, and Dionysos begins to plot. After all, Bacchus is dual in nature: “god of the intensities of terror, / god of the gentlest human peace.” But even then, Dionysos does not lose his composure. In fact, his whole act rests on his suave seduction of Pentheus to act against his own interests. This might be another bizarre link to our political present. Once facts and sensible discourse (embodied in the person of Tiresias) fail to convert, the god resorts to wiles: to the coaxing of subterranean inclinations. Our centuries-old politics of manners is proof that this method of persuasion often trumps the verdict of facts: from Andrew Jackson throwing his forceful simple-man’s vocabulary, to Reagan hiding all culpability behind an actor’s poise, to Trump assuring his audiences with that brash New York baritone. But Bakkhai’s Dionysos embodies the message that true overcoming—on a cosmic, moral, and political scale—requires the synthesis of these two facets of life: reason and passion. The Dionysian leader does not so much “use” either as simultaneously “channel” both in an expression of truth.

Dionysos’ duality is best expressed in a scene where a group of herdsmen encounter the Bakkhai on a journey through the woods. When the men chance upon them, they are peacefully sleeping in three circles, each around the female elders of Thebes, the daughters of Kadmos: Ino, Autonoe, and Agave. Upon the beasts’ braying, the women spring up, “somehow instantly organized”: “with snakes that slid up to lick their cheeks, / some (new mothers who’d left their babies at home) / [cradling] wolf cubs or deer in their arms and [suckling] them.” Honey drips from their thyrsi, and the Bakkhai strike the ground to produce wine, or scratch with their bare hands to draw out milk. But when the herdsmen attempt to attack, in order to return Agave to her son Pentheus, all hell breaks loose. The women tear entire calves and bulls apart (“chunks of flesh dripped from the pine trees, blood everywhere”) and descend upon two villages, where the men’s swords fail to draw any blood, yet the Bakkhai’s thyrsi wound them badly.

This gory scene foreshadows Pentheus’ fate. The dramatic ironies of the sections that follow, that of Pentheus’ sprucing at the hands of Dionysos, and his death on the mountain, are impeccable. (Important also to note here that Pentheus means “grief” in Ancient Greek.) After Dionysos personally dresses and makes him up, the leader wonders aloud whether he looks like his mother. “I was tossing my head back and forth like a maenad inside the house,” he says, in a statement ripe with dramatic pathos. When the god offers to correct his hair, he happily submits: “You redo it. I’m in your hands.” And when Dionysos tells him he will be victorious, that someone other than he will return him home, Pentheus exclaims: “My mother!” The god tonelessly affirms him.

In the section that follows, the Bakkhai reiterate their mission: “the great clear joy of living pure and reverently, / rejecting injustice / and honoring gods.” Then they make their call against Pentheus: “Into the throat / of / the / ungodly / unlawful / unrighteous / earthborn / son / of Echion / let justice / sink her sword / !” Carson mirrors the Bakkhai’s fluctuating intents. Earlier, when she speaks of “skylarking,” and compares the Bakkhai to a fawn leaping free of its hunter, the prose cascades down the page like a peaceful river. Dionysos is freely dialectical here: both hunted and hunter, frolicking while calling out for punishment against Pentheus. But when actually rousing Agave and the women for Pentheus’ death, her words become tightened at the center of the page, turning into literal swords.

Carson translates the scene that follows from two perspectives: that of the Bakkhai, and a servant following Pentheus on his last journey. Once again, Pentheus’ pathos is sharply etched, when he calls out to his mother for mercy, and Carson’s lines chop back: “But she / was foaming at the mouth, / was rolling her eyes, / was out of her mind.” The irony continues into Agave’s slow coming-to. After she has fixed her son’s head onto her thyrsos and paraded it for the rest of the Bakkhic women, she says to herself: “What a fresh bloom he is, / just a kid, just a calf – / here, see the down on his cheeks, / the long soft hair.” She exclaims that she wants her son to nail this head to their house, as a trophy of her hunt and the success of Dionysos. Kadmos talks her awake from her trance. Even the sky begins to brighten, like a sign that Agave and the women were moving through an alternate dimension of their own, or that of the god’s: a pre-modern Upside Down. In response to her realization, Kadmos says the one line that could sum up all of tragedy: “Truth is an unbearable thing. And its timing is bad.” Agave remembers nothing of her deed, and where the text is missing in the original Greek, Carson works wonders through her curt poetry, this time of reckoning: “His body. / His dear, dear body. / This is my son. / This is what I did.” Here we learn that Agave too had denied the god, and this is her punishment.

What is amazingly refreshing in Bakkhai is the unquestioned triumph of Dionysos and, especially for the western reader, the pre-Christian (and pre-Roman) sense of Dionysian order as proper to humankind. The Bakkhai say so again and again: “ancient, / elemental, / fixed in law and custom, / grown out of nature itself” is Dionysos, and he’s therefore to be respected. This is amazing, bearing in mind that Dionysos did not fare well under the Romans. The Senate saw his followers as a secretive and subversive counter-culture: seditious to both civil and religious law. These cults were mostly lead by women, and at gatherings they outnumbered men. The Bacchanalia was banned by the edict of 186 BC, and its members threatened with the death penalty.

Carson captures the renegade spirit of the Bakkhai in her verse. This is how they speak of Dionysos: “He is sweet upon the mountains / when he runs from the pack, / when he drops to the ground, / hunting goatkill blood / and rawflesh pleasure.” The compound words may seem unmistakably Carson’s, but they’re in fact direct translations. The women refer to Dionysos’ emissary (the young religious leader) as their “comrade.” Later Livy, whose accounts of the cult were filled with exaggeration and outright lies, writes that Bakkhic devotees’ nocturnal rites included loud and haunting music, feasts, drunken orgies, murder, and even cannibalism. Shockingly, the Romans also accused early Christians of human sacrifice, and believed that the host was dipped in the blood of a child. In the second century AD, Christians turned these accusations against the pagan in their war against witches’ covens. The latter may not be surprising, given that Dionysos models what became the Devil for fear-mongering Catholics and Protestants, from medieval superstition through to the Inquisition, and all the way up to the Salem witch trials. Just like Dionysos, the Devil sprouts horns, shape-shifts into animals, and communes with and empowers women who submit to him with magic powers.

Here Christianity’s complete reliance on this other order—of the unknown, of magic, and of women’s sexual and moral liberty—is loud and clear: “Whether the Belief that there are such Beings as Witches is so Essential a Part of the Catholic Faith that Obstinacy to maintain the Opposite Opinion manifestly savours of Heresy,” reads the Malleus Maleficarum of 1486.. The Malleus is the Inquisitors’ guidebook to the identification and persecution of witches, and it answers this formal query with a mighty yes. To read this bizarre and famous work today is to learn that witches’ covens were seen as a threat to the entirety of Christendom, including its masochistic-misogynistic dominance over all forms of spiritual resistance. In Anne Carson’s translation, the whole of this strange history glows through the page. Most notably in an early chorus where the poet inserts this chant into the original play: “green of dawn-soaked dew and slender green of shoots … green of the honeyed muse, / green of the rough caress of ritual, / green undaunted by reason or delirium.” These wizardly treats are endemic to her version.

And later, this spell by Dionysos himself: “Spirit of earthquake, shake the floor of this world!” This, however, is all Euripides. The difference between Bakkhai and the rest of Judeo-Christian history is that in the Ancient Greek play, Dionysos and the women are owed our full regard, and they triumph—though at a cost to Thebes. In Bakkhai, which won first prize at the Dionysia festival where it premiered in 405 BC, this god that reaches way down into our evolutionary roots and affirms everything about our bodies and desires—in good measure, as he repeatedly instructs—along with all the women who enjoy his blessings, are portrayed as impregnable forces. The play shows us that we cannot not revere them, as we’d do so at great cost to our own freedom and integrity. Dionysos is the “rawflesh” prelude to the human imagination that is inescapable even to its finest and most noble pursuits.

This message feels as important today as it did over 2,400 years ago. Hence the commissioning of this ravishing new translation by the Almeida Theater, where it was first staged in July of 2015 starring Ben Wishaw as Dionysos, Bertie Carvel as Pentheus, and renowned director James Macdonald at the prow—better known for his work with contemporary authors. The production opened to raving praise of Orlando Gogh’s score and Ben Wishaw’s acting, which the Guardian described as “insinuating and dangerous,” and “the most perfect portrayal of androgyny.”

With its due relevance in mind, let’s let Bakkhai have the last word: “Many are the forms of the daimonic / and many the surprises wrought by gods. / What seemed likely did not happen. / But for the unexpected a god found a way. / That’s how this went / today.”