Gravity

“She’s gone to the U.P,” they would say, or, “She gone up North.”

Despite the fact that, technically, up North and the U.P. were two distinct regions. When it came to where Marilyn had disappeared to everyone knew it was the U.P. even if some referred to it, not really correctly, as up North.

It’s late at Carl’s and James makes his joke about the things waiting outside in the trees, above the gravel parking lot. It’s not a joke, really, because there’s no punchline, but people think of it as James’s joke anyway even though it’s more like a refrain or a half-finished fairy tale. It’s been a tough year, and there’s an unspoken hope that things are about to turn around for the better.

And yet the subject of this evening’s small talk at Carl’s is, as usual, Marilyn, who has incrementally transformed her personal tragedy—the loss of her two boys in a snowmobile accident—into a legend, and herself into something beyond a martyr--something mythical. When she becomes too familiar, and her presence demythologizes her aura, she disappears into the U.P. There is only one practical way to get there and that is the five-mile-long bridge across the Mackinac Straits, the bridge from which just last year a woman—in her car— was blown by a 50-mile wind gust off the bridge to plunge into the November Lake Superior water 150-feet below.

“The creatures have enlarged themselves,” James begins. The Pepsi clock above the bar reads 11:28. The way it will go is that, depending on various stages of drunkenness people will let James talk. They will even be gracious and welcoming. They will encourage details. It will be, for a brief time, like a workshop: tell us more, hold on; give us more details; what do you mean “hanging” in trees;” how did they get there; where’d you get this idea.

“It’s not an idea,” James says. One of his large ears is either purple or tattooed.

“You can’t bullshit a bullshitter,” Frank, James’s half-brother, responds.

“Maybe Marilyn left because of the ‘creatures’,” someone says. Carl, the owner and bartender, has heard this all before and is bored but knows that, very soon, things will veer deeper yet into boredom and James and his posse will disperse into the cold night.

Lisa has been listening and finally has this to say.

“I don’t think she’s up North at all. I don’t think she ever left.”

Lisa is the youngest of the group and has been waiting for a very long time—almost a year—to interject and change the trajectory of the story. Her own mother was a borderline narcissist and she has no interest in the attraction to Marilyn’s supposed vanishings to some place in the U.P. Lisa wears silver and turquoise bracelets and rings that give some people the impression she is from Arizona or New Mexico. Her skin is dark, dark for this part of Michigan.

“Cold enough for you yet?” Frank asked her last winter, the coldest one on record. Lisa lives on Mercy Street above the hardware store and all year it smells like spring in her apartment because of the fertilizer.

“Lisa doesn’t think she’s up North,” James repeats to the group, signaling one last round with a thing he does with his fingers above his head. Then he says, apropos of nothing: “Lisa never smiles.”

“I bet she doesn’t believe in the tree-things either,” someone else shouts from down the bar. Then laughs. No one wants to describe them, the things in the trees, because to do so would sound downright foolish. What: long snouts? What: hunched backs? Yellow eyes? Sharp teeth? Who could say these things—even if they were true—and not come across as a halfwit?

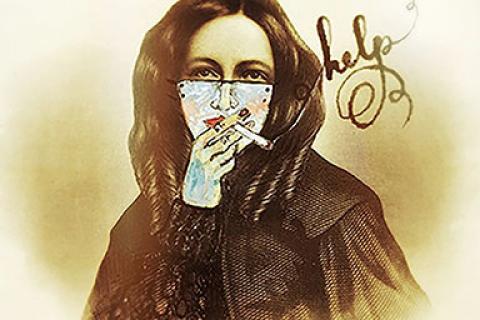

Lisa has soft features and smooth black hair and drives a red Cherokee. Before she came to Michigan she worked in Dayton, Ohio at an accounting firm where a software error resulted in an unaccounted for one hundred and seventy-eight thousand dollars that she used to move here and begin, as they say, a new life. The possibility of erasing who she was and what she had done. Her soft campaign against Marilyn is strategic, although Lisa has no endgame in sight. Marilyn is known for two things: the tragedy re: her children and the fact that she is what they call an artist-type. She wears flowing robes or shawls and even sandals in winter. Her decorated cigar box phase gave way to her shadow box phase without anyone even noticing.

“Oh I believe in them all right,” Lisa says. “They’ve gotten bigger.” In Ohio she drank her beers in poured pints but here she knows better and now doesn’t even need to say anything to Carl for him to bring her a longneck of whatever is one dollar.

“Not bigger, enlarged,” James says.

If she had to guess Lisa would say James is in his fifties but the only time she sees him is in this bar and under its distorting conditions and dim lights. In the way certain men do, James possesses the space around him while others flounder.

“Has this ever happened before?” she asks him.

“What?”

“The enlargement.”

“It’s been happening,” he says, “over time. They gorge, they get bigger.”

“You tell her!” Frank says as if they’re having a debate.

Lisa always does this then: gets out a cigarette and a lighter as if to. But she won’t. She can’t. She’ll wait until she’s outside.

“Okay so if she’s not in the U.P. where is she?” James asks.

On the TV above the bar the extra inning Tigers game is just over and there’s the lonely clapping of one person. Can’t hit for hitting someone says. There is now fog drifting in the blue light of the sulfur lamp outside. And there is the soft rumble of a car or two starting up in the parking lot.

There’s a phone ringing behind the bar and Carl lifts the receiver and puts it down again. It’s near closing time and there’s no reason to talk on the phone. If it’s an emergency they can reach him on the second phone, the private line, beneath the counter at the other end of the bar.

“Who’s up there with who?” asks James.

“Marilyn. With them,” says Lisa.

If she wants to insert herself into the familiar narrative about Marilyn then she needs to make a space in it, a gap, and then use that gap to expand her own detoured version. Lisa suddenly misses Dayton and the fine, marbled museum she’d spend Sunday afternoons in during hot summer days. It was there she learned about perspective and vanishing points and, in a way, how to vanish herself. She could be very still on a bench for a very long time.

Lisa gets up, walks over to the window, leans in, cups her hands and looks up into the trees. She comes back to her stool. She’s only met Marilyn once, at a charity softball game for the burned down Elks Club; a fire started, it turns out, by a stove purchased with the funds from a previous charity softball game for the remodeling of the kitchen. It was clear to Lisa right away that Marilyn exerted a kind of gravity that gently pulled those around her into her orbit and that these satellite people, after a time, repeated her bullshit stories as if they were fact. Who would lie about losing two children in an accident? Why would anybody do that? Since there could be no good answer to questions like that; they weren’t questions that were asked. The wrecked snowmobile in Marilyn’s garage that she uncovered and showed to people when they came around was, Lisa knew, nothing more than a prop. And the place Marilyn disappeared to periodically in the U.P. was, Lisa also knew, not really a place at all. It didn’t exist.

How much of Marilyn’s life was a prop, a fake, an impersonation? Lisa didn’t have to think long about these questions to know the answer. She saw behind the façade right away, a façade betrayed by little gestures. Did Marilyn know she’d met her match in Lisa? Lisa wasn’t sure. How smart was this Marilyn woman? And what sort of smarts were we talking about?

It’s last call.

“Why would she be up there with them?” Frank asks, circling back to what someone said earlier.

Carl has already turned down the heat and cleaned the bathroom.

“Ask the expert,” James says, nodding to Lisa.

But Lisa has never actually seen things in the trees.

Lisa slips on her black leather jacket with the torn and stitched sleeve and looks ready to leave. This lends an air of expectancy to what she’s going to say and already she can feel the gravity shifting from Marilyn to her. If she can just hold off a little longer before saying anything, if she can just let the slight anticipation build, if she can just find the right words and the right cadence to address the question of why Marilyn might be up in the trees with the enlarged ones.

Above the bar is a framed picture of Osama bin Laden with an X of black electrical tape over his face. Last month, for the first time, someone asked who it was, and it was then that Lisa understood how easily history slips away. Like her own. She wants so hard to be new again. She is suddenly afraid to leave the bar and go outside and to her Jeep parked beneath those branches. The wind pushes against the windows. It seems to know something. Does Carl understand this? Does he appreciate the situation? Is that why, after last call, he cracks a bottle open for Lisa and sets it before her on the wiped-down-for-the-night bar? She wants to ask him to become her ally in displacing Marilyn, but she can't be sure whose side he’s on and in this moment she is trapped between the bar and the empty parking lot.

Carl isn’t laughing but something about him suggests laughter. He has tucked in his green flannel shirt and Lisa notices all the rough, awkward, nail-sized holes punched in his leather belt. She is shocked. She looks away. Outside the window there is shadowy movement above the Jeep. In her mind, the trailer is burning. The trailer Marilyn is hiding in. Not someplace in the U.P. Not someplace up there with the enlarged ones in the trees, either. But rather in the abandoned trailer just a mile or so from here, in a cold swampy outwash plain, a concoction of put-together words Lisa’d never heard in Dayton.

She shudders and Carl puts his hand on hers, gently. She could go home with him tonight but those holes in his belt! She hears a scratching at the door and in a fleeting thought wonders if she could spend the night here, in the bar, in a back room or something, until the light comes up.

“Don’t worry, it’s locked,” Carl says but that just makes her worry more.

All the talk of the creatures in the trees has gotten to her. Plus the overheated bar, the beers, the black night. Plus Carl’s dangerous belt. And the Towers-eyes looming from above the bar. And the burning trailer, the enlarged ones waiting outside.

And that museum in Dayton, the way it held her in place, grounded. Lisa feels herself floating now, really, just above her barstool in a way that Carl senses but can’t understand.

“I’m right about Marilyn, right?” she says more than asks.

“In that?”

“In that everything. She never went up North. She never lost kids in a car wreck, she . . .”

“Snowmobile accident.”

“Okay: She never lost kids in a crash.”

“Snowmobile crash. Against a tree and into a ditch. Broken necks.”

Lisa turns the half-finished bottle of beer onto its side, watches it foam across the bar.

“Get out,” says Carl. He looks tired. He looks like he just wants to go home. “Get out.”

Lisa feels nothing beneath her.

“Fuckin’ annoyance,” she says.

“Get out. Get out!”

Lisa leaps, grabs the bottle, wants to scream, I’m already out, I’m already out! I’m out I’m out I’ve been out I’ve always been out help me bring me in God help me please I’m out I’m out I’m out!

*

She thinks about sleeping in the Jeep, recklessly. Bundled in the lumpy sleeping bag in the back. Instead, for now she sits still in the driver’s seat, her mittened hands on the steering wheel, the car keys on the seat between her legs, her breath slowly fogging the windshield, thinking back to her Dayton friend killed sophomore year in the drive-by shooting whose mother she, Lisa, looked upon with unaccountable disdain at the funeral, as if the stupid, wilting, palliative flowers at the casket were somehow her fault rather than the florist’s, as if she deserved the knock on the door at 1 am, and the young, pale-faced officer’s face as stunned-looking as if he were reporting his own daughter’s death to himself.

And then she does this. She crawls back over seat tops, deeper into the weirdly geometry-ed Jeep parked there outside Carl’s like some stupid hulking metal thing. She shudders, tunneling deeper yet into the jeep and then deeper still into the sleeping bag. What is she doing here, beneath the trees with those apocryphal creatures looming? Leaving Dayton was just another false move, she thinks, a misdirection. How many Marilyns must she slay?

In the morning, she is new. Somehow. Sore and cramped, but new. Outside the Jeep in the empty parking lot Lisa stretches. The sun is out, fierce and brilliant. There is a wind and she can hear Lake Michigan in the distance. She looks up into the trees and they are, of course, empty.

She smiles.