For Love of Stalin

As a child, the teachers in primary school taught us the slogan, “as Children of the Revolution, Stalin loves and protects us.” We all repeated it every morning after the national anthem.

Before that, as a toddler, I had stopped speaking gibberish and began to pronounce words. My father sat at the dinner table in our home wearing his overalls. He worked as a carpenter and drank straight out of a more-than-half-empty bottle of vodka.

“Stop Stalin dead,” I said.

“I heard that!” he said.

I felt a sting on my head. The next thing I can remember, I hung upside down in the chicken coop by a rope tied by my feet in the cold.

“Daddy!” I said.

He stood there for what seemed forever while steel wire held me suspended in the air. He left and came back with a cup of probably vodka. After I stopped crying, he untied my legs, and took me down.

“To denounce the Great Leader is a horrible crime and must be punished,” he said.

I believed him from that day on. I felt grateful for my father teaching me lessons that way. Whenever he searched for reasons to discipline me, he often found them. My childhood hardened me, toughened me up for what I would eventually do.

I knew Stalin personally although I never met him in person. His image adorned everyone’s wall. His eyes peered into the soul. Everyone knew and loved him. All the prominent newscasters on the radio and newspapers told us of the wonderful things he did. He enjoyed smoking tobacco and drinking like me. I always imagined him having a glass full of vodka and a smoke with me as I gazed at his picture in front of my dining room table. Stalin’s genius guided the progress of our Great Nation.

When I first learned from the newspaper, the Pravda, that sinister forces plotted against our Glorious Leader, I felt sick to my stomach. What could I do to help? The need for decisive action started after the assassination of Sergey Kirov, Stalin’s dear friend, by conspirators in high ranks of the government. I also read about the job opportunities in the interrogation department of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, known by the acronym, NKVD. This agency protected the Revolution from spies and saboteurs. I submitted my application and got hired in a day. My new career choice pleased me because I hated my job as a custodian at the health clinic. They ignored my criminal record of assaulting a man while I was drunk outside a bar—I probably should have put it on my resume. I got the opportunity to protect the Revolution in the exciting counter-espionage field.

The man who previously filled my position, Dimitri Malenkov, went missing along with most of the “Old Guard” NKVD personnel. These people were all associated with the conspirators who killed Kirov. The rest of them confessed to espionage and high treason. They all died, even that pornography obsessed Yagoda, the previous head of the agency. The old boss confessed to charges of treason and murder publicly in the “Trial of Twenty-One” along with twenty other counterrevolutionaries. The Soviet Supreme Court ordered them to be shot like rabid dogs. His replacement as chief, comrade Nikolai Yezhov, searched his old boss’s house and found thousands of nude photos of women. I listened to the trial on the radio when the Ministry of Information broadcast it to the whole country. These proceedings served as a shining example of the Soviet justice system that I felt glad to be a part of.

I worked in the Lubyanka, a trapezoid-shaped building built around courtyards with thick green walls and deep cellars. It was once the headquarters of the All-Russia Insurance Company before the Revolution. Columns and arches decorated the exterior around each window. Parquet floors with rectangular designs came under my boots when I went through the main entrance each day. This building of bourgeois origin’s ceilings had decorative murals of nymphs playing and dancing on the edge of a forest. Administrative offices on the floors above the basement provided the space for all the employees doing the paperwork.

The basement depths held a labyrinthian expanse of cells. Its thick cement walls stifled the groans and cries of our interrogated prisoners. No natural light penetrated here. The halls reeked of disinfectant and the rooms were overheated. A strong lamp with the switch outside the cell lit up the prisoner’s enclosure above a small table for questioning. Prisoners subsisted on black bread that was stored in a small pantry on the first floor.

A spiral staircase connected to a cellar for us to put a revolver to the back of the neck of the executed. The chamber had a heat lamp and a desk at the center and a blue tarpaulin floor. It was the chief source of the smell of disinfectant since the place needed to be cleaned after every use. Custodians would come and wipe the floors with mops.

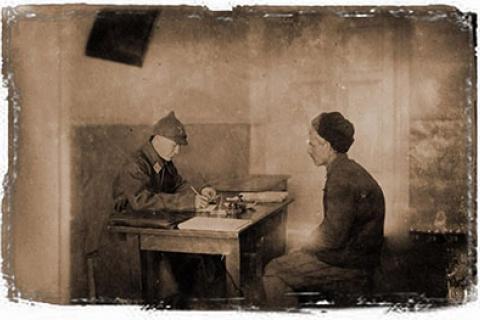

Throughout my tenure as an employee there, we always followed a strict protocol. A troika of officers in the field would decide the charges the soon-to-be prisoners faced. Once at the Lubyanka, they were seen by an inspector in the reception area and documented, fingerprinted, and then cavity searched. We dragged them down the stairs in their underwear and put them in a cell. My coworkers and I would interrogate them until they gave up and confessed. In the rare case they would not give up, the prisoners would be brought down deeper on the quiet floor where the guards talked to each other with clicks of the tongue and sent back up to us at least once a day. This way, the rooms of our floor were always full of new prisoners. They signed a white paper listing their charges to make their confessions official. Sometimes the note got red with blood. After these procedures, a judge reviewed their cases to determine the best course of action to deal with them.

It took me only a few interrogations to recognize the innocence of most of the prisoners. Kicking someone on the floor or punching a man in the face did not always bring the truth out of them. The lucky ones went to the Gulag while the rest died by execution. I noticed, as time went by, more and more people came through inspection and into the cellars. My work hours increased from fifty to a hundred hours a week. Our job became more demanding since we now needed a staggering twenty people to confess per shift to meet our quotas.

What could justify this grand commitment? Think of cancer. To treat cancer, a doctor may have to amputate an arm or a leg. Espionage and other crimes against the state were like a malignant tumor. If the doctor did nothing, the diseased tissue would spread through the body and kill the patient. We acted as the doctors treating the body of the Soviet Union. We may remove more tissue than what was afflicted by killing extra people, but how else can we be sure to rid the Soviet Union of the infection? We, as the Children of the Revolution, had a sworn duty to ensure Stalin’s vision of a new Socialist Utopia came true.

Those sinister forces existed everywhere. I read about them every day in the Pravda before I left for work. The newspaper dedicated at least a page to report on spies and saboteurs. It provided countless editorials praising our heroic work in thwarting the anti-revolutionary forces.

I showed up to the warm Lubyanka basement early for work that Moscow winter morning. I had just finished drinking a few mouthfuls of vodka from my flask to loosen myself up for a long day’s work. I brought a small container for a single shift or, in this case, three for the double I worked that day. The breakroom’s pale-yellow walls, wooden floor, large dining room table with glasses, and sink provided us NKVD agents with a place to take a break from our stressful jobs to drink vodka with our cigarettes and socialize. The room’s old-fashioned ornamental light with stained red glass hung over me. I wished the department supplied us with liquor. We all had to bring our own. Just about everyone drank in the breakroom. The cloud of tobacco smoke in the air that accumulated at the end of the morning shift often muddled my view of the white ornate ceiling and dimmed the light.

Sometimes, the monotony got to me. An endless supply of prisoners needed our persuasion to confess. I divided the prisoners into two groups: the cooperators and the defiant ones. Sure, I might run into those cooperators that sign the white sheet the minute they see the dark green Lubyanka basement most of the time. However, the defiant ones who refused to confess unless you bludgeoned them with your fists came at least once a shift. They might even spit or bleed on my dry-cleaned uniform. Both types had one thing in common: they all signed the confession slip.

I put my flask back in my uniform jacket and waited for my partner, Lavrentiy Ivanov. He always came in right on time. He worked longer hours than I did and rarely ever imbibed. I never saw him drunk. He tirelessly beat and questioned prisoners with an incredible fanatical devotion. Whenever I needed a break to relax and lighten the mood in the breakroom, he wanted to interrogate another prisoner. Whatever the situation, I could always light up a Troika cigarette and take a sip of vodka on the job, so I did not care. The day went faster after I drank a pint.

I watched the grandfather clock strike eight in the morning in the breakroom. Lavrentiy came in as he always did. He walked right in front of where I sat.

“Ready for another hard day’s work, Igor?” he said.

“I sure am.”

“Ok, we’ve got to see twenty prisoners from cell block A this shift. Our jobs are important, try not to get in a stupor this afternoon.”

We got to the first ten prisoners one by one, all cooperators, and made quick progress on the quota that morning. I wanted to go to the breakroom to see the rest of the guys, but I knew Lavrentiy had his heart so set on a promotion to lieutenant that he would have us interrogate every last inhabitant of the Soviet Union on our shift if he could. We visited the eleventh prisoner in his cell. The man wore blue overalls. He had the look of fear in his eyes as he sat across the table.

“I’ll sign anything you want. I’ve heard about this place,” The prisoner said.

“You, Dimitri, confess fully to the charges of attempted sabotage? Put your signature here,” Lavrentiy said and pushed the slip to the prisoner. The condemned signed the document and gave it back.

“We need the names of ten of your friends or acquaintances and any other details you can provide about them. Please write them here,” I said.

I passed him a sheet of paper and a pencil. He sat there scratching his head as he wrote them down and passed the paper back. Our prisoner wrote ten names in neat handwriting on the paper and circled the name, “Marien Balagula.”

We had strict orders to get the names of at least ten other people from every prisoner. These unfortunate comrades or deserving criminals would get arrested the following day or even later the same day. If the incriminated person could not come up with these names, we would arrest all his or her neighbors. If an agent found an address book while searching their home with the required number of names in it, we had no need to interrogate them for it. If anyone worked as a spy or saboteur then, odds were, their closest friends did also. We had to be careful. Quotas had to be met.

“Why is one circled?” I asked.

“He will be difficult,” Dimitri said.

“Why?” Lavrentiy said.

“I grew up with him. He never started fights, but other kids would beat him up. He would usually lose but never gave up until he was knocked unconscious. You guys might have a hard time with him. After he broke someone’s nose, he gave up fighting completely. Marien used to be a fall-over drunk until our Stalin became leader. He told me he stopped because he wanted to better serve the Great Genius—to be a good, useful Communist,” Dimitri said.

“We are grateful for your information but based on your crimes you will probably be sent to hard labor for ten years,” Lavrentiy said.

“That is better than getting put in an unmarked grave, I guess,” Dimitri said.

We left the cell and locked the door behind us.

“Easy day,” Lavrentiy said.

I took a long swallow from my third flask.

“Yes, more like him and we will fill up all the Gulags and run out of bullets,” I said.

I remembered the morning clearly, but that afternoon my memory got fragmented. I recollect talking to a prisoner about the whereabouts of a probable spy ring—but forgot the topic of the conversation in mid-sentence. My partner took over on my behalf and asked the person we questioned the name of the organization he talked about. He said he worked for the East India Company after I recall him telling us he had acted alone. We both knew he just made that up, so Lavrentiy knocked the desk over and kicked him square in the face. When prisoners lied to us, and they did frequently, my partner responded with violent rage. Although he never really cared when I did not tell the truth to him about how much I drank anytime he asked. The proceeds of the rest of the interrogation remain a mystery to me.

A great deal of time passed during which I have no recollection. I regained cognizance as we walked the halls towards the next prisoner’s cell. As we paced the halls, I took a drink and Lavrentiy gave me a bad look.

“You usually knock the prisoner to the floor when you punch them in the face. You did not do that in the last interrogation,” he said.

“It’s nothing,” I said.

“Do you love Stalin?”

“Of course.”

“Show him that you do—stop getting so drunk on the job. More than half this department is inebriated by noon.”

The next moment I can recall, a prisoner’s hand lay extended in front of me on the table. I grabbed it and stuck my lit cigarette into it. The prisoner cringed and tried to pull his hand back.

“Igor—Igor—he is a cooperator Igor—he gave us everything we need,” Lavrentiy said.

I let him go. Next thing I knew, we stood in front of a cell at the end of block C.

“Prisoner number thirty-eight on our list, Marien Balagula. Charged with high treason, aiding the enemy, subterfuge, sabotage, and inciting a revolt. He will go to the cellar for sure,” Lavrentiy said.

I ran out of vodka. My mind came back, and I usually remembered when I got to the last drop. Running out angered me. I wanted to make this prisoner suffer.

We opened the door and sat down with Marien.

“Stalin is with me, I won’t con—” our prisoner said.

I got up and punched him from across the table. His chair flipped backwards, and he fell off it to the floor.

“I’m sorry—you were speaking?” I asked.

“Our Wise Leader will punish you for doing this to an innocent man,” Marien said.

Our prisoner stood up with his fist clenched.

“He’s not going to help you, scumbag,” I said.

“The Gardener of Human Happiness watches over all of us,” Marien said.

“You are a traitor, charged with high treason. The reward for that is death. Give in and we’ll make it easy and painless,” I said.

“This is just a terrible mistake; the Brilliant Genius of Humanity will fix everything,” Marien said. “You are the people betraying our Leader. You may be NKVD agents, but I am a truth teller—a vicar of Stalin—telling people about the wondrous things the Master Planner of Communism is doing! I let anyone know who will listen about the Savior of the Russian People. My neighbor, Vladimir, couldn’t read. He didn’t even have a radio—and I enlightened him about our Glorious Leader! Now he believes as the many I’ve shown do.”

I threw another punch at Marien’s face. He grabbed my fist in mid-air, turned around to my side, and twisted me around the table in an armlock. I stood hunched over as he applied pressure on my hand. A stinging pain went up my appendage. I looked at the floor.

“This is mine—come any closer and I’ll break it,” Marien said.

Lavrentiy grabbed the prisoner’s hands and tore them off me. I regained control of my appendage. We threw Marien to the floor. Lavrentiy and I spent an exhausting half hour kicking him. This prisoner’s interrogation marked the first time in a while I ever broke a sweat beating a defiant one. I needed the exercise after all these easy interrogations, but both my legs throbbed after the encounter. My body had to stay strong to protect the Revolution and serve Stalin.

“There is much more from where that came from—I promise you. Going to confess?” Lavrentiy said.

Our prisoner lay there on the floor, motionless, and bleeding from the nose and mouth.

“Not to these ridiculous charges or anything! You people don’t deserve to be State Security agents!” Marien said.

We went to the break room. Geliy, an older interrogator, sat in an armchair smoking a cigarette and drinking a tumbler of what looked like whiskey.

“Hey comrades! I never see you guys here,” Geliy said.

“Probably because we are busy working.” Lavrentiy said.

“Very funny—” Geliy said.

“Is that what I think it is? English, Irish?” I said.

“English; aged twenty years—cost me a lot of rubles on the black market. Want some?” Geliy said.

He knew my next question. I not only wanted to taste it, I needed to drink to unsettle my nerves.

“Of course,” I said.

He handed me the bottle. I poured myself a tumbler full of it and gulped it down. The whiskey tasted like sweet wood. I liked it, lit up a cigarette, and smoked with him.

“That stuff is great,” I said.

“We are here because we are having trouble with a strongly defiant one,” Lavrentiy said.

“Oh, those. I like them. I can have a go at him,” Geliy said.

“No! He’s ours! We are fully capable of getting him to confess,” Lavrentiy said.

“Charges that would lead to execution?” Geliy said.

“Yes,” I said.

“Well, you could always sign the confession for him. They keep the slip but will not check its authenticity,” Geliy said.

“That’s forgery. That is just wrong, and I am no criminal,” Lavrentiy said. “We should check the handbook on how to deal with this problem.”

I grabbed the manual on top of the bookshelf next to me.

“Get to the chapter on nonlethal alternatives to kicking and punching. Please read it aloud,” Lavrentiy said.

Under the chapter 10 subsection xii heading, “Alternative Interrogation Methods” went as follows:

If beating a prisoner fails to produce the desired results, it means the interrogator must try new methods of extracting the truth out of them. The first one to attempt is a mock execution. Devalue the prisoner and blindfold him or her. Bring him or her to a cold room and tell the captive that they will be shot if they move. They can be left blindfolded for hours without the personnel necessary to—

“That’s it. We could do that and leave him in a cellar to get other confessions,” Lavrentiy said.

Executions never occurred anywhere except the kill room, but we got a large black blindfold, rifles, and a wooden wash bucket out of the supply cabinet and went to Marien’s cell. He sat there on the ground, twiddling his thumbs next to the chair in his underwear.

“Have you come to release me?” Marien said.

“No, you worthless piece of excrement. Fighting us is useless and you are not leaving here alive,” Lavrentiy said.

“You are going to another room. Stand on the bucket, and if you move, we will shoot you,” I said.

“Stalin will protect me,” Marien said.

We brought him into a chilly concrete room near the staircase, tied a handkerchief around his head, and turned him to face the wall. I lit up a cigarette as both of us watched him stand.

I finished smoking, and we sneaked out to interrogate other prisoners. We came back a half hour later to see our prisoner pacing back and forth with his blindfold off.

“I knew I was not going to be executed. The Dear Father saved me,” Marien said.

I took my partner aside. Both of us were frustrated and tired after the long day.

“We had better ask the boss for the extension before we clock out,” I said.

“He is unusually difficult,” Lavrentiy said. “I mean, there are people yelling at us and fighting us for days, but no one is foolish enough to believe Stalin protects them here. Even the people trying to fake their devotion to Stalin break down after the first day.”

Lavrentiy filled out the paperwork and I went upstairs to get the approval on the interrogation’s extension. The clerk took it for processing. I went back down to get my jacket and smoke in the breakroom. In mid-cigarette, a young courier in a neat NKVD uniform came in and asked for my name and gave me a quick notice for indefinite approval. This happened often enough, but I noted the speed at which the request came back at us.

***

We finished most of our rounds and stood in front of Marien’s steel-reinforced cell door. Lavrentiy kicked it to wake him up and we busted inside. Our prisoner sat in wait in the corner of the cell curled up. Lavrentiy held his hands up and put brass knuckles on each of his fingers.

“It’s time to answer our questions,” I said.

“There’s no need for any,” Marien said.

“Sure there is,” I said.

Lavrentiy got down and punched the prisoner in the face.

“Tell us what Stalin’s birthday is,” I said.

Marien had a nosebleed. He wiped the drips of blood coming onto his lip. He continued to sit there.

“It’s the eighteenth of December 1878,” Marien said.

My partner punched the prisoner again.

“Correct, but do you know what time?” I asked.

“No one does,” Marien said.

I kicked the prisoner across the face with my boot. He lay across the floor.

“What is Stalin’s favorite book?” I asked.

“The Knight in Panther Skin by—” Marien said.

Lavrentiy jumped on and put his knees on top of the prisoner’s shoulders. He decked him across the face.

“By—by Shota Rustavel. Just one of them,” Marien said.

“You are lying and not just about yourself but about your personal work with the capitalist spy ring,” I said.

“No! No! No—I am not,” Marien said.

“I am talking about the forces you conspired with,” I said.

“You two think you are serving Stalin, the Leader of All Progressive Mankind, but you are not—instead, you are leading the Proletariat over a cliff,” Marien said.

The prisoner spit out blood to his side.

“I am keeping the Revolution alive and going until it can spread to Germany,” I said.

“You are undermining justice in our Great Nation,” Marien said.

“Give me a brass knuckle,” I said.

Lavrentiy took the weapon off one of his hands and gave it to me. I took a deep breath and grabbed the prisoner by the neck. The piece of metal gave weight to my fist and helped me bring down havoc on Marien’s ribs and nose. My hands got red stains on the outsides of them.

***

I saw the custodian walking around the hall with pincer pliers and a ball-pein hammer on his belt. I got the man’s attention.

“I think we’re going to have to commandeer your tools, sir. A defiant prisoner awaits us,” I said.

“This is not approved by the manual,” Lavrentiy said.

“We should improvise. We could be inventing new methods and furthering the art of our occupations. Enough of the old grind,” I said.

“Fine. Everything up until now has been ineffective,” Lavrentiy said.

“How long?” the custodian said.

“Just for a few hours,” I said. “And we need rope.”

“There’s twine in the supply closet,” the custodian said.

We took the materials we needed and put them in a shoebox. I could hear Marien humming the tune to the Internationale as we approached his cell. I kicked the door and we came in. Our prisoner sat in the interrogation chair in front of the table, waiting for us.

“What hand do you write with, Marien?” I said.

“My right…” Marien said. “What’s that?”

“It’s a box of party favors,” I said.

“Party?” Marien said.

“Yes, and we’re all here to celebrate,” Lavrentiy said.

“It’s the day Lenin passed away and Stalin took leadership of our Great Nation,” I said.

“It’s already the twenty-fourth of January?” Marien said.

“Yes,” I said.

I opened the box and took the twine out.

“Stay in the chair while I secure you,” I said.

I tied the prisoner to the flimsy wood piece of furniture with the whole spool and put tight knots in the layers of twine without slack. Marien’s hands were free to be on the table.

“We are only doing Stalin’s bidding,” I said.

“You have the wrong man,” Marien said.

“You are lying to us about what you think—about who you are,” Lavrentiy said.

“I am Marien Balagula, a shoe factory worker. I stitch the soles to leather. I believe in the Dictatorship of the Proletariat led by Stalin. The Inspirer and Organizer of Victories is everywhere.”

“Stalin is not here,” Lavrentiy said.

“But he is transcendent,” Marien said.

I removed the top off from the box and took out the pliers. They had curved ends to them and looked like a semi-circle when I opened them. Lavrentiy got the hammer.

“Open up and don’t move or I’ll make this worse,” I said.

“This is insanity,” Marien said.

“This is the way things are, as Stalin willed it,” Lavrentiy said.

My partner raised the hammer and hit Marien on his left hand against the desk. I heard a bang. The prisoner cringed and took back his arms away from the table.

“Keep your left hand on the desk! Open up!” I said.

Marien did not lower his jaw. I jammed the metal instrument in his mouth, I went for his front teeth, and pulled hard to yank them out. Our prisoner flinched and the tool slipped off.

“Look at me. What is Louis Armstrong’s real name?” I asked.

“I don’t kn—” Marien said.

Lavrentiy delivered a blow to the center of Marien’s left hand with the round part of the hammer. Marien flailed his arm in pain.

“Don’t move,” I said. “Let’s put him on the floor.”

I hit him in the lips with the end of the pliers and broke a piece of his teeth off. I kicked him to the floor off the table. He sat on the chair across the ground.

“The Dear Father knows what you are doing is wrong,” Marien said.

“He is only aware of what he is told. He ordered us to do this,” Lavrentiy said.

“This is all just a test,” Marien said.

“Stalin pays me to do this. I love my job. Look at my Rolex. See how it shines,” Lavrentiy said.

My partner pulled down his sleeve and showed the prisoner his watch.

“The Great Genius works in mysterious ways that no one man can understand. He thinks hundreds of moves ahead at chess,” Marien said.

“This is the end of this game,” I said. “Open up.”

I jammed the pliers into Marien’s mouth and gripped his bottom front teeth with the pliers and put my foot on his head. I pulled with all my strength, up and down, until the two teeth were freed.

“You won’t need these when you’re dead,” I said.

“Stalin will punish you for what you do. He has a plan for me,” Marien said.

Blood dripped onto the floor from the condemned one’s mouth. The way the prisoner lay, shaking in pain; it had a ghastly beauty with the way the shadows came in from the lamp, like a gory surrealist painting about a dream-like object.

***

A few weeks went by and Marien got thin on the Lubyanka bread diet and continued to have an empty smile. Lavrentiy and I ran through the door to pay him a visit. The prisoner gave a grim look of desperation and futility across his face and greeted us with raised eyebrows and a deep frown. Marien crept up from the ground.

“Not happy to see us?” I said.

I lit up a cigarette and took out one of my flasks.

“Want to have smoke or a drink with me?” I asked.

“I don’t do that,” he said.

“At any time you want, I’ll stop what we’re doing and give you a few shots,” I said. “It’s good grain vodka.”

“That won’t be necessary,” Marien said.

“Or maybe I’ll pour it down your throat,” I said.

“He won’t like you if you don’t drink with him,” Lavrentiy said.

Marien had no response and stared into the ground.

“Let’s see if your hand is still broken,” I said.

I put the cigarette in my mouth. I grabbed Marien’s left index finger and pulled it backward. The prisoner let out a shrill scream.

“Oh, it hasn’t healed yet,” I said.

Marien looked away from me, turning his face. I put my foot behind the prisoner’s feet and pushed him on the ground. The condemned one fell, and I stepped over him. I shoved the lit end of my cigarette onto his cheek. The spear of tobacco bunched up and stopped smoking. Our prisoner recoiled. I littered the ground with the butt. Lavrentiy came around and kicked Marien in the head.

“Nothing really matters—there isn’t meaning to any of this. Give up already,” Lavrentiy said.

“The Mastermind of Socialism will help move civilization past capitalism, if you would let him,” Marien said.

“You are a blood sacrifice,” Lavrentiy said.

“The Wise Man of Steel would never have me bring false witness against myself,” Marien said.

“Stalin made an unfortunate mistake,” Lavrentiy said.

“There are no coincidences, only the will of the Father of Nations,” Marien said.

“Stop the suffering,” I said.

“I have devotion to the one and true Premier of the Soviet Union. I am not your target,” Marien said.

“You were brought in here by agents in the field,” Lavrentiy said.

“I was apprehended with two other men while I was helping a blind man with his groceries from the store across from my house,” Marien said. “Three NKVD agents came to me, said my name, and threw me to the ground. They handcuffed me and brought me here without telling me why I was arrested.”

“It’s senseless, isn’t it?” Lavrentiy said.

“There’s a reason I’m here to meet you all,” Marien said. “The Grand Architect of Progress will let me go once I have proven myself. He sees all that we cannot.”

“Stalin is just a man who hired us to kill you,” Lavrentiy said.

“The Great Benefactor has a design for the world,” Marien said.

***

One day on the way back from work one early morning, I walked past a banner of “Iron Felix” Dzerzhinsky hanging on the masonry above the subway stairs. The picture never really caught my eye until now. The man presided as head of the CHEKA, the organization that kept Soviet Russia intact during those early days of the Revolution. It eventually got replaced by the NKVD. What would he do?

I drank in my living room later that night looking at my picture of Stalin. The exhausting and frustrating times during the day I had trying to get Marien to sign the slip affected me. I grew fond of him and looked forward to my time with him. Since he was a meek man of gentle persuasion, I regarded him as one of the unlucky ones, undeserving of his fate. He fit the definition of a good Communist. He never gave up and argued with us at every turn, but no one ever held up believing Stalin would save them.

I saw my hacksaw inside my utility closet behind my fishing gear.

***

I showed up to work early the next morning with the cutting instrument in a knapsack. Lavrentiy had arrived there earlier than me and sat at the desk in the breakroom surrounded by papers. I stood next to him, drinking from my flask.

“Marien has gained notoriety. Geliy and the others are talking to him outside of his cell. They are fascinated with him,” Lavrentiy said.

“He’s unbreakable. We could just wait until he starves to death.”

“That would be a betrayal of the justice system.” He gave me a half grin. “Worst of all, it would make us look bad to our superiors.”

“I think we've had him here since the beginning of January and now it’s the seventeenth of February.”

“We’ve had him for forty days.”

“Every defiant one we’ve had gave up in, at most, three days. If three days is a lifetime then forty days is an eternity.”

“It’s an embarrassment.”

“I have a lot of respect for him.”

“He’s the excess fat on a filet mignon that must be cut off.”

“What are you doing?”

“I’m looking for Marien’s arrest order.”

“Good. I brought this in.”

I took out my hacksaw from the knapsack and put it on the table in front of him.

“Nice touch, though I doubt it’s an official method.” He picked up a paper and stared into it. His eyes lit up. “Here it is. Arrest authorized by none other than Iosif Vissarionovich Djugashvili himself!”

Stalin was rumored to sometimes sign warrants, and the reasoning and circumstances around this habit drew foggy speculation.

“If this doesn’t break him then the Great Leader cannot help him regrow his legs.”

“We can use this. We need to stop the insulting remarks and show others we are capable. We’ve been trying to put him through enough pain to sign the paper but with no results.”

He folded the arrest order and put it in his pocket. We got up and walked to the front of Marien’s cell.

“I’ll do the talking,” he said.

We opened the door and entered to see our prisoner standing there smiling.

“Hello, comrades Lavrentiy and Igor,” Marien said. He sniffled and probably smelled the vodka I took a sip of before coming in. “Igor, you should give your heart to Stalin—I hate to hear what Sosa is going to do to you two after he hears what you have done to me. He has great plans for me.”

“We came to talk about that,” Lavrentiy said.

We all sat down at the table.

“What about it?” Marien said.

“Well, we hate to tell you—Stalin signed your arrest order,” Lavrentiy said.

“I do not believe it. You are just playing tricks on me,” Marien said.

“Look at the order,” Lavrentiy said.

Marien took the paper and saw it. “That is… his signature—you are not lying to me.” His eyes widened. “In fountain pen….”

The prisoner appeared devastated and took a deep breath. I could hear him failing to hold back sobs.

“Will you sign the paper now, please? We are both getting exhausted from trying to get you to confess to your crimes,” Lavrentiy said.

“We both worked long hours, Marien. I need to spend time with my family. We have other prisoners to interrogate. Think of what we have to go through,” I said.

“If it is Stalin’s will that I die, then I accept. He must know I will be a spy in the future,” Marien said.

Our prisoner signed the order. The man loved Stalin so much that he endured an aeon of torture and accepted his sentence only because our leader himself signed his arrest warrant. I, too, loved Stalin with all my heart but I could not imagine going through his situation and continuing to unconditionally feel the same way for the “Great Genius.” The tough lessons my father gave me came into my head. I never had these strange stirrings of emotion to my memory. I began to understand the prisoner and felt sorrow for his fate. Something like this could happen to me and our leader would not save me.

We submitted the signed confession to the inspector upstairs knowing what fate the judge would issue for our prisoner. The courier came back to the breakroom in less than five minutes and handed me the execution order bearing the red stamp underneath the judge’s signature. This mark meant death. I drank a whole flask to hide any emotional display. Lavrentiy sat there across the table from me looking satisfied as if he single-handedly foiled a plot to kill Stalin.

“You drank that fast. Come on, we must get Marien. He truly has been a tough safe to crack,” Lavrentiy said. “Can you do the honors?”

“... I will.” By doing Marien in, I could make sure he died as painless a death as possible. Lavrentiy never wanted to get his uniform bloody.

I went to the supply cabinet and got out my pistol. We opened the door to see Marien with his hands covering his face.

“Alright, it is your time. Walk with us,” Lavrentiy said.

Our victim followed us down the cylindrical stairs with his head down into the kill room. Stalin did not seem like a god among mortal men. He signed the death warrant of a man who loved him more than life itself. I wondered how many people we condemned had similar situations. The whole nation worshipped him, and we did these things in his name. Those who did not carry the same harmonious tune eventually ended up here. Even those who chanted in key could have wound up here if they were unlucky enough. We were the leader’s attack dogs.

My stomach started to hurt. My eyes watered. I tried in vain to choke back tears. I wiped the ones that ran down my cheek away with my hands before my partner could see. I opened my last flask of vodka and guzzled it all right there.

“You done?” Lavrentiy said. “Let's get this over with.”

I pushed Marien over the desk as he faced the piece of furniture and cocked back the hammer on the revolver with my arm. The prisoner looked back at me with the corner of his eye.

“Any last words?” I said.

“I die still a patriot! For Stalin!” Marien said.

I aimed at the prisoner’s neck, pulled the trigger, and let my victim’s lifeless body fall to the floor.