Shoes

Tiziano Colibazzi was in my class at The New School this spring. He was doing a dual degree in poetry and non-fiction in the M.F.A. program. Early on, I learned that he was a psychoanalyst. We spoke briefly, once, on a street corner, about his life, but that now seems like a luxury. Covid hit; we were on Zoom. In those squares. I recall Tiziano gesticulating that he was losing his mind, with the kids home all day—home schooling—he had seven-year-old twins he shared with his ex-husband. If they come out of their room," he said, "I may have to go to them." And they did. "They are very very curious," he said. I recall heads bobbing up and down, just below the threshold of the screen. Eyes wide open. Sometimes, they fell asleep there, on his lap, one on each side, as class continued into the night. I'll never forget those squares—it felt as though we were all on a lifeboat, through the roughest of seas; if any one of us seemed to be falling in, arms would reach to pull them back... And all around, there was so much suffering and death.

"Shoes" was Tiziano's final piece for the class. It took my breath away. He beautifully invents a form when words fail, when a trauma is so deep, so obscene, it cannot be held… There's something astonishing in the movement of the piece, as it enacts the experience of post-traumatic stress. And he reminds us of what happens if we do not remain vigilant--act up, speak out… As I read it, I returned to that place where as a child, I could not find words. And then I experienced waves of grief, for lovers and friends—and humankind—through AIDS and Covid...

—Zia Jaffrey, author of The Invisibles: A Tale of the Eunuchs of India, professor in The New School's MFA program, and contributor to Toni Morrison: The Last Interview and Other Conversations (forthcoming, Melville House)

"Schwarze Milch der Frühe wir trinken sie abends"

"Black milk of the morning we drink it in the evening"

— from "Todesfuge" by Paul Celan

I. Beginnings

Mine is not a fetish, yet my relationship with shoes is older than my memories.

I would call it a strained relationship, occasionally acrimonious, with its ebbs and flows. It has fallen prey to infatuations and fads, family conflicts and bouts of masochistic self-deprivation. I have suffered blisters and taken them in stride as a price to pay for elegance, I have rebelled against the unspoken mandate to keep the heels from showing the stigmata of use, the gnawing at the edge which exposes the wood under the rubber, and belies the sloppy moral fiber of a neglectful attire.

At least that is what some people say in Italy.

My mother used to say—and still does—that I go through shoes like rolls of toilet paper. She used to blame my posture and way of walking or standing, supposedly inherited from my father in a straightforward Mendelian fashion, for the fact that after a month one heel was considerably more worn out than the other and that the tips where damaged.

“You keep dropping and dragging the tip of your foot!” All my sins were on display. I guess she thought she could fully understand people’s personalities from their shoes, in the same way that the old phrenologists classified characters by looking at the shape of someone’s head.

Despite, or rather in opposition to these injunctions, I proudly owned only one pair of shoes throughout my last year of high school. The left rubber sole had a hole right where the arch was supposed to find support, a capital sin in the world of flat-footed people. I am not sure what drove this experiment in Franciscan virtue, beyond my wish to push the lack of financial means we suffered during those years to its limit so that it could become a sign of honor.

When I moved to the US, my relationship with shoes slowly became more practical. The winters were harsher and it was not possible to wear shoes conceived for a Mediterranean climate in the arctic temperatures of Chicago winters. The snow would wet the flimsy hand-stitched soles, seep through them and imbibe my socks, which would end up feeling like frozen gloves. I had no other choice: I would put my Italian shoes in a bag and change once I got to the hospital. I opted during my commute for a pair of white Adidas, which jarred with my suit as I waited on the L platform. I felt thrilled by this freedom: nobody seemed to care or to look at me with disapproving glances.

I could not escape the fact that I was born and lived for twenty-five years in Italy, a place where shoes are a proxy measure for being a “put-together” human being, that my father’s family comes from that region of central Italy mostly connected to shoe-making, the Marche region, that my aunt owned for some time a shoe store in one of the banlieues of Rome and that my cousin Francesca, her daughter, was deprived of “real” shoes as a child, having to wear “corrective” ones for years, supposedly to address her flat foot problems. Of course, these therapeutic shoes did not come in fashionable designs or pleasing colors. Rather, they seemed to be manufactured with the sole intent of mortifying vanity, a modern equivalent of the hair shirt, looking like a leather black box promising future salvation in exchange for present suffering.

Francesca used to look on with envy and frustration like the Little Match Girl in Andersen’s story when new samples of women’s shoes would arrive at her mother’s store. She’d touch the glossy heels, draw slingbacks with her crayons during the boring afternoons doing homework behind the counter. She is an attorney today. Last time I visited her in her new apartment, once we had finished dinner, she proudly walked me to what she’d call “The Room.” A long walk-in closet of curved shape, such as you can only find in old buildings in Italy, stacked up to the ceiling with shoes, arranged like books on shelves, none of them in boxes, with the only purpose of being admired and of providing a belated revenge to their owner for her childhood torment. I thought, why not put some exemplars on a coffee table in the dining room, like one of those Taschen books which saves one from stale dinner conversations. I asked Francesca how often she’d wear them. She picked up one of her favorite pairs, some leather shoes with crisscross black and white stripes, heels covered by a print evoking an inverted Tour Eiffel: stroking it like a pet, she said wistfully: “Maybe once a year, I do not want them to get ruined.”

Shoes fall into the category where we put parts of our life that are essential and never think about until we lose them: parents, water, marriages, and health. Just like with everything that one takes for granted, the most fundamental aspect of these chiral man-made objects escaped me. I never fully appreciated their tragic side or the survival advantage they confer, till I went on a trip with my sister Carmen in 2012. Carmen wanted to relocate to Berlin, due to the lack of job opportunities in Rome. I had planned to help her, hoping that with my financial and moral support, she would eventually find her way in Germany, whose economy was booming.

At that time, I had begun to read books on the history of same-sex relationships. I bought my first one the previous winter after I visited the Homomonument in Amsterdam: three pink triangles commemorating the victims of the Holocaust. I do not remember much of that particular trip. I have been to Amsterdam multiple times since then. I know it was freezing because my feet kept bothering me. I know I thought of buying sturdier shoes there but preferred to ride out the discomfort and go for books, as if books and shoes, head and feet, had to compete with one another.

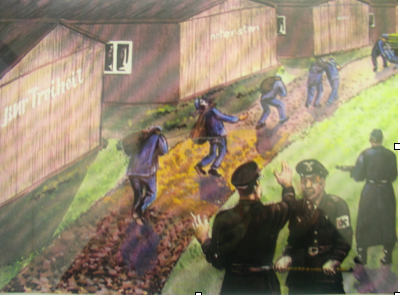

I told Carmen I was going to make a point of visiting each Denkmal in Berlin as well as Sachsenhausen, a KZ, or concentration camp, known for its sadistic treatment of homosexual prisoners, also known as pink triangles, during WWII. These were the Schuhläufer, prisoners forced to soften the boots and shoes produced for the German army by marching for hours along the inner perimeter of the KZ. The experience of one of these KZ prisoners, Joseph Kohut, is the subject of the memoir Die Männer mit dem rosa Winkel (The Men with the Pink Triangle) written by Hans Neumann under the pseudonym of Heinz Heger and published in 1972. Few remember today that this is the reason why the pink triangle later became the emblem of the LGBTQ+ community. Young men, raised in the comfort of Mitteleuropa, were arrested under the infamous Paragraph 175 that punished homosexuality in the German Reich, frequently tortured, and then shipped to the camps to be Schuhläufer.

II Schuhläufer

A Denkmal is not a memorial, and it is not a monument. It is the embodiment of Time which has become Thought and occupies a finite portion of Space: Denk (thinking, thought) + Mal (time/s). This composite word strikes me as very German: you do not re-member an event. You need to think about it.

I pick up on my way out from the Sachsenhausen KZ a copy of Heger’s ’s book. A passage strikes me as the kernel of the story of the “pink triangles”: forced fellatio. Forced, as it were, because fellatio is really what the prisoners wanted after all. Every homosexual prisoner, or any homosexual for that matter, should feel honored to suck any straight man, even a convicted murderer. And, of course, a few beatings may make one more compliant.

“Mit Püffen und Schlägen zwangen sie mich dann, da ich mich nicht freiwillig dazu bereitfand, abwechselnd an ihrem Glied zu saugen, das sie in meinem Mund pressten.”

"Then they forced me with blows and beatings, because I was not freely willing to suck, taking turns between one and the other, their member, which they pressed in my mouth."

III Après-Coup

Carmen and I come back to Berlin. We have spent an entire day in Oranienburg, where the Sachsehausen KZ is located. Exhausted, yet unexpectedly unperturbed, we decide to head for a restaurant in Gendarmenmarkt.

In Sachsenhausen the poplars shudder with their shawls of snow

we looked at one another: “We thought we’d feel much worse.”

A heavy air

drips

down

on our

restaurant libations:

we were staring at the plates: our puny conversation

our meal

had no

worthy

purpose,

no

meaning no

courage no dignity no

context or voice no

rest.

I’d left my ration of words outside

the gate; I’ve none to spare.

Blood still trickles through the gravel

in this neutral zone near

the wall of bricks, hundreds of ashen

bricks kneaded by the fear

of being shot through the feet,

then march in vain with boots

of plywood: wounds that will not

heal. It could have

been me: a Schuhläufer

marching and testing

boots, till my feet are

too maimed to be of use

to the shoe factories

How am I to approach the KZ topic? Verse, prose, a power point? Some say we should not speak at all, let alone write, about these matters. How are we to never forget then? Illogically, being gay seems to give me a complete pass: I can write or speak with “authority” about gay victims —not the other ones, of course—without being accused of appropriating, misappropriating, banalizing, or even worse defiling other peoples’ tragedy.

It’s all about playing the “gay card.”

IV Denkmal Pilgrimage in Berlin (2012)

I happened to be in Berlin with my sister Carmen. We just arrived, she from Rome, I from New York. We plan our day. My sister says, resisting my attempts to create a day schedule for our Berlin pilgrimage: “So very American” she adds, “always having to make the day “PRO-DU-CTIVE.”

In fact, I tell her, the way to cope with terrifying chimeras has always been to make

them quotidian. That’s how people survive. The blending of triviality

into memories renders them inoffensive, a vaccination of sorts against forgetting.

She doesn't buy it. How can you make tourism out of it? Horror in a to-do list? I ignore her and look over travel guide suggestions:

Denkmäler: Saturday morning

Breakfast at our Luxury Hotel (Starwood collection)

1 Gedenkstätte Sachsenhausen

Lunch break 12:30–13:30 on your own.

We recommend bringing a lunch box.

(Oranienburg is a ghost city, reminds me of Decatur, Illinois)

2 Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas (Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe)

3 Denkmal für die im Nationalsozialismus verfolgten Homosexuellen (Memorial to homosexuals persecuted under National Socialism)

4 Denkmal für die im Nationalsozialismus ermordeten Sinti und Roma Europas (Monument to the Sinti and Roma of Europe murdered during National Socialism)

5 Spa appointment, Sofitel am Gendarmenmarkt 18:30 – 19:30

6 Dinner at Lutter & Wegner am Gendarmenmarkt 21:00

The hotel staff gently advises: “We do not recommend visiting all these sites in one day. Your list is ambitious but I understand you want your day to be productive.”

V Sachsenhausen

Leafing through Kohut’s memoir, I read the entire piece while I am on the U-Bahn. I read in a desultory manner. From the middle, from the end, never from the beginning and always without committing. Fragments flash before my eyes in a confusion of time lines. I am too overwhelmed by the KZ to even attempt to stitch all this into any narrative or care about verb tenses being consistent. Kohut’s story is just one of many I imagine: Heinrich, Franz, Ludwig, Stefan and countless others.

1937 Ludwig is from Münster. Thirty-two years old, architect, 64.0 kg, 1.64 meters. Brought overnight. Arrested under Paragraph 175—Der § 175 des deutschen Strafgesetzbuches—the law punishing sodomy. His ex-lover turned him over.

The paragraph reads: Die widernatürliche Unzucht, welche zwischen Personen männlichen Geschlechts oder von Menschen mit Thieren begangen wird, ist mit Gefängniß zu bestrafen; auch kann auf Verlust der bürgerlichen Ehrenrechte erkannt werden. (The unnatural fornication which is committed between persons of the male sex or of men with animals must be punished by imprisonment; also it can be punished with loss of civil rights.)

1937 Sanchsenhausen KZ; this ought to be a resting place: Ludwig crossed the iron gate. A motivational banner wrought in Gothic Script, the hope of freedom in exchange for labor.

“Arbeit macht frei”

The silent air of glass scratched rarely by sharp and lightning shrieks. Limes, Liminal, Limit, Great Wall, The Wall, Boundary, Hortus Conclusus, cloister of cruelty. What is commonplace outside, grows absurd inside. Absurd = Ab-Surdus. Out of tune, dissonant or deaf to reason. Not simply contrary to reason, but reasoning impermeable to sound and speech in the sense of Logos.

1938 Schuhläufer Kommando. The prisoners march along the perimeter of hopelessness, toeing the outer bound of an island of barbed folly. They are testing combat shoes for straight soldiers till the leather is softened enough by the blisters of their feet. Sores dried with the gravel and the ashen dust falling down from a grey infinity. Can they march with two left shoes? With a fractured foot? A gunshot below the heel? One by one these hypotheses must be tested. On them. At dusk, back to the wooden clogs. No socks. No blankets—in order to prevent sex in the barracks. Splinters of wood lodge under nailbeds. Open wounds are dull on hard wood. Maximum duration of stay for the Häftlinge is six months to a year. With one exception: the Pink Triangles. They die faster. Refractory cases are sent for medical emasculation or forced copulation with the opposite gender.

2012 Sachsenhausen Wet and cold feet. I tell my sister I should have worn better shoes, sturdier shoes. Nothing makes you feel lonelier and more naked than wet shoes and wet linen socks in November. A hole in the left wooden sole, right in the middle, soaks the entire leather. Primo Levi said that if you were given two choices in life, food or shoes, you always ought to choose shoes.

1945 Ludwig released from KZ to a Berlin in ruins.

1946 Stuttgart Ludwig deemed not a real victim. His pension was denied. Compensation not applicable. Absurd to pay a non-victim. Either you are a victim or you are not. It’s quite binary. Since homosexuality is still punishable, he is still a criminal.

1947 Mannheim § 175 Redux. Ludwig is back to prison under Parapgraph 175. Time spent in Sachsenhausen does not count towards his punishment for what brought him to the KZ. He must still pay. Therefore, he should go back to prison and do the entire jail time.

VI Denkmal für die im Nationalsozialismus verfolgten Homosexuellen

2015 Ebertstraße, Berlin. Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas and right across the street Denkmal für die im Nationalsozialismus verfolgten Homosexuellen.

The Denkmal across this street is worlds away from that more official site

with spartan slabs of grey concrete waves for what remains of the murdered

hands of Europe. The other site grabs me from across the street, purposefully

absconded among the bushes. Inside the solid block are scenes of guilty

longings, silent kisses, cached recordings of illegal loves visible

through the aperture in the concrete closet.

VII Fire Island, Pines.

The high tea scene in the Pines is de rigueur. I have not been here in years. Today, I notice that the drag code has been democratized. One does not need the whole dress and wig thing, which is great but time-intensive. Some guys wear pashminas over a polo, others carry a fan or purse while dressed in an otherwise more gender-conforming style. A burly man is dancing next to me, while I speak to my friend Don, who notices that nowadays just a pop of drag is finally within everybody’s reach. This man’s eyes are closed, and he appears to be in mystical communion with Deborah Cox’s Remix playing loudly. He is wearing a black tank-top and some swimwear, reminding me of a Tom of Finland image, sort of the hyper-masculine Pines beach butch guy. I look down at the floorboard and realize that he is pirouetting on a pair of vinyl crimson-red high heel shoes, proud to “mix it up,” wearing them like an amulet, as if whispering to everyone around: I do not give a fuck. After all shoes can also be subversive.

Bibliography

Triangle rose Michel Dufranne, Milorad Vicanovic, Christian Lerolle. Quadrant Astrolabe, 2011

Die Männer mit dem rosa Winkel Heinz Heger. Merlin Verlag

Triangle Rose Régis Schlagdenhauffen. Éditeur Autrement, 2011

Images Sources

Image 1 https://joepwritesthehistoryofberlin.wordpress.com/2013/02/15/sachsenhau...