What Lies Above, Beneath, and Apart: Hemingway and Hemingway

Let’s start with a thought experiment.

Step One: Imagine two huge icebergs, one representing Ernest Hemingway’s writing and the other representing everything else in his life. Imagine that these two icebergs sometimes bump up against each other and sometimes drift apart. Imagine that these icebergs are like the one Hemingway uses to make an analogy with effective writing (especially his): its “dignity of movement . . . is due to only one-eighth of it being above the water” (Death in the Afternoon).

Step Two: Imagine that you decide to sculpt a new, smaller iceberg by synthesizing core elements of the two huge ones. Imagine that you challenge yourself to make seven-eighths of this sculpture visible above the water even as it has its own dignity of movement. Imagine that you develop what you regard as a viable vision of this iceberg.

Step Three: Imagine that you undertake the task of converting this vision into a 6-hour documentary about Hemingway’s life and work for PBS. Imagine how you will craft that conversion so that it both remains true to the sculpture in your mind’s eye and appeals to a contemporary PBS audience.

I’ll pause to give you some time to conduct all three steps of the experiment.

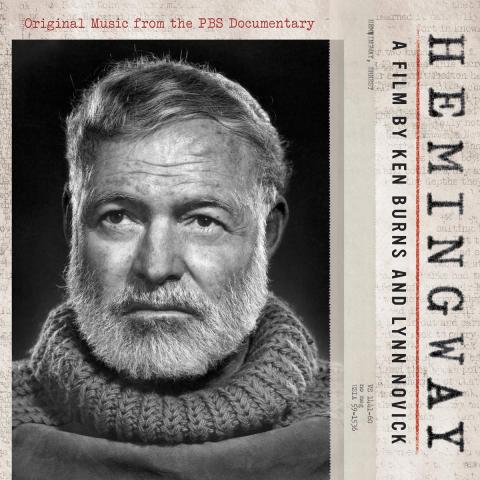

I start with this thought experiment for three reasons (1) It helps capture the ambitious and daunting task that Ken Burns and Lynn Novick took on in making Hemingway, their three-part documentary that recently aired on PBS (April 5, 6, and 7). (2) The experiment highlights the larger purpose of the documentary, its goal of replacing the myth of Hemingway with a far more accurate and layered view of the life and the writing. The myth constructs him as the epitome of machismo, a man with prodigious appetites and the will and means to satisfy them as well as a man with extraordinary talent who produced an enduring stream of what he liked to call true sentences. Burns and Novick retain the idea of the talent but complicate everything else in ways I’ll discuss below, and, in so doing, they reposition the writing within the life. (3) The experiment invites each of us to think about how we would have constructed the relations between the writing and the life in our own distinctive ways.

These three reasons, in turn, underlie my reflections here. On the one hand, I want to celebrate Burns and Novick’s execution of their challenging project: in breaking through the myth, they construct a much more complex and interesting Hemingway, a strange blend of strengths and weaknesses, virtues and vices, who has had more than the usual allotments of good fortune and bad. On the other hand, when I took Steps One and Two of the thought experiment, I gave more attention to the writing than Burns and Novick do, and this attention led me to a different vision of the sculpted iceberg than the one that emerges in their documentary. I want to discuss my sense of the writing iceberg not to find fault with the documentary but use it as a spur to move some of what’s submerged there above the water line of the synthetic one. First, though, a little more on Burns and Novick’s Hemingway.

In keeping with its myth-busting purposes, the documentary gives considerably more attention to the life than to the writing for two interrelated reasons. First, the myth about the life dominates Hemingway’s legacy in American culture. He is a figure that many people who have never read his writing know something about—and even have opinions about. Changing those views requires a new biography more than new analyses of the writing. Second, the genre of documentary lends itself to a greater focus on the life because it is a fundamentally narrative genre, and because Hemingway’s life is filled with tellable events. Giving pride of place to the writing—or even giving it equal prominence—would be extremely difficult because its narrative raw material would be the single event, repeated multiple times, of the writer sitting down to write. Hard to imagine that even the PBS audience would sit still for much of that.

In keeping with the goal of humanizing Hemingway, Burns and Novick give the greatest attention to his intense and fraught relationships with his four wives, Hadley Richardson, Pauline Pfeiffer, Martha Gellhorn, and Mary Welsh. Using Geoffrey Ward’s script, voiced by Peter Coyote, to supply the baseline narrative, the filmmakers show the good, the bad, and the ugly in Hemingway’s behavior toward these women. Ward’s script includes testimony from the women themselves and Burns and Novick enlist accomplished actors to voice that testimony: Keri Russell (Hadley), Patricia Clarkson (Pauline); Meryl Streep (Martha); and Mary-Louise Parker (Mary). More generally, Burns and Novick’s skills as visual storytellers lead them to interweave these voices with Hemingway’s (ventriloquized through Jeff Daniels) and with a range of other materials—photographs, newspaper articles, and newsreel footage—that often bring in other events. Although Burns and Novick do not offer substantial new revelations about Hemingway’s life, they call attention to some things that have circulated more widely among scholars than among the general public. Especially noteworthy is their attention to his interest in bending and even blurring standard gender roles and the consequences of that blurring for sexual encounters. Above all Burns and Novick succeed in making visible what lies beneath Hemingway’s behavior throughout his adult life, identifying both distant and proximate causes of it. Among the distant causes are his mother’s increasing disapproval and his own disappointment in his father; his being jilted by his first love, Agnes von Kurowsky, the British nurse he met in Italy, while serving as an ambulance driver during World War I, and whom he thought he was going to marry; his witnessing of combat and his own wounding. The more proximate causes include his willingness to promote an image of himself that eventually he could not live up to; his multiple concussions; his alcoholism (called his “overdrinking” by Mary); and of course the complex personalities and histories of the women he loved. Burns and Novick also make judicious use of interviews with Hemingway’s son Patrick, with Hemingway scholars and biographers, and with the psychiatrist Andrew Farah as they round out their portrait of the artist as a fascinating and flawed, charming and repulsive, young, middle-aged, and aging man.

Even as they give greater prominence to the life, Burns and Novick make a valiant effort to highlight the writing and to explicate its power. The first image they show is the typescript for the opening of A Farewell to Arms, and they continue to sprinkle images of manuscript pages throughout the documentary, including ones for all the novels, for the nonfiction books, and for multiple short stories (“Up in Michigan, “Indian Camp,” “Hills Like White Elephants,” “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” and more). In addition, they employ the actor Jeff Daniels to read numerous excerpts from the writing, and Daniels does an exemplary job of bringing out the tones and rhythms of Hemingway’s remarkable prose. Furthermore, as Daniels reads, Burns and Novick guide their audiences to engage more deeply with the writing by putting evocative images on the screen, ones that capture moods while opening up rather than closing down interpretations. To pick just a few telling examples: a dock in the gloaming to illustrate the setting of “Up in Michigan”; an oar pulling through the still water of a lake for the ending of “Indian Camp”; the exterior of stone building with a substantial set of stairs leading to an empty street for A Farewell to Arms and its final sentence (about which more below), “After a while I went out and left the hospital and walked back to the hotel in the rain.”

Having prompted this engagement with the writing, Burns and Novick then rely on the commentary of a wide range of thoughtful, well-informed experts to explain how and why it’s often so powerful (and sometimes not). These experts include Hemingway’s recent biographers, Mary Dearborn and Verna Kale; notable contemporary fiction writers, including Michael Katakis (executor of the Hemingway estate), Tobias Wolff, Edna O’Brien, Tim O’Brien, Mario Vargas Llosa, Paul Hendrickson, and Abraham Verghese; and first-rate literary critics, including Stephen Cushman, Miriam Mandel, Susan Beegel, Marc Dudley, and Amanda Vaill. They even bring in John McCain to discuss his life-long engagement with For Whom the Bell Tolls.

All these commentators are smart, engaging, and insightful. Wolff, for example, characterizes Hemingway’s effect on the writers who came after him by saying that “he changed all the furniture in the [writers]’ room.” Edna O’Brien frequently pushes back against the common view that Hemingway was a thorough misogynist and goes so far as to suggest that parts of A Farewell to Arms, her choice for his best novel, could have been written by a woman. Other arresting comments include on-target descriptions mingled with praise: Hemingway remade the language (Vaill); he goes beyond previously accepted boundaries (Katakis); he works against the modernist grain of difficulty that characterizes the fiction of James Joyce and William Faulkner (Cushman); he articulates a view of war that no one had ever articulated as clearly and powerfully before (Wolff); he creates a male character in “Hills Like White Elephants” whose subtle but incessant pushing to get his own way women will readily recognize (Mandel). Furthermore, in keeping with the myth-busting purpose of the film, these commentators also discuss what they regard as ethical failures in the man (his seemingly gratuitous meanness to other writers, even those who had advanced his career) and aesthetic ones in the writer such as Across the River and into the Trees.

Yes, yes, yes, I nod. And then I think back to my thought experiment and what I would want to do to make what lies beneath the writing more visible. If I were to convert my vision of the sculpted iceberg into a documentary film, I might well use the same commentators, especially Wolff, Edna O’Brien, Cushman, and Mandel, but I would ask them to comment more consistently on the interrelations of three aspects of the writing: (a) the material Hemingway works with, (b) his treatment of that material, and (c) how that treatment guides readers’ inferencing about the characters and events in ways that significantly influence readers affective, ethical, and aesthetic responses. I even think such commentary would appeal to the PBS audience. To illustrate what I have in mind, I’ll discuss two texts that figure prominently in the first episode of the documentary (entitled “The Writer”), “Indian Camp,” and A Farewell to Arms.

In “Indian Camp,” as Geoffrey Ward’s summary efficiently indicates, Nick accompanies his doctor father on an early morning trip to the eponymous camp, where he watches his father perform a successful but extremely painful Caesarean section with a jackknife on an Indian woman who undergoes the procedure without anesthesia. Once the operation is over, Nick and his father discover that the woman’s husband, who has been lying in the bunk above his wife, has slit his throat. That discovery changes the direction and emphasis of the story; rather than being one about birth and new life (and Nick’s father’s horribly insensitive treatment of the Indian woman—he tells Nick that “her screams are not important”), it becomes one about suicide and death. The ending, which Daniels reads with his typical skill, brings the story to an affecting conclusion, as Nick first asks his father questions about suicide and about dying and then retreats into his own thoughts. Here are the story’s last lines:

“Is dying hard, Daddy?”

“No, I think it’s pretty easy, Nick. It all depends.”

They were seated in the boat. Nick in the stern, his father rowing. The sun was coming up over the hills. A bass jumped, making a circle in the water. Nick trailed his hand in the water. It felt warm in the sharp chill of the morning.

In the early morning on the lake sitting in the stern of the boat with his father rowing, he felt quite sure that he would never die.

Burns and Novick bring in Wolff and Cushman for commentary. Wolff makes the astute observation that Hemingway is working with sensational material but handles it in an unsensational way. Cushman nicely underlines the paradox of the ending, the juxtaposition of Nick’s knowledge that he’s going to die with his denial of that knowledge. Good stuff, as far as it goes. But let’s go a little further beneath the surface.

Hemingway makes the sensational unsensational by restricting his audience to Nick’s perspective and, thus, having us take in the events as Nick does and then follow his struggle to process them. Furthermore, Hemingway’s treatment of that struggle demonstrates his impressive ability to deploy both dialogue and the representation of consciousness to guide his audience’s inferencing. Hemingway uses the dialogue to show that, although Nick’s father answers Nick’s questions with genuine care for Nick, the answers themselves are not particularly helpful because his father is not able to adopt Nick’s perspective. When Nick’s father says that the difficulty of dying “all depends,” the natural follow up would be “it depends on what, Daddy?” but Nick’s silence signals that he has now stopped trying to get insight from his father.

Cushman’s comment on the ending perceptively points to the way the details of the scene play into Nick’s denial or evasion. But digging deeper reveals how much Hemingway both trusts and subtly guides his audience. Hemingway reports Nick’s misguided conclusion without any narratorial comment because Hemingway knows that his audience knows that he knows that Nick is in denial here. (That’s a mouthful, I realize, but one I hope you’ll find worth chewing on.) What’s more, Hemingway affectively aligns his audience with Nick, despite his denial, in part by inviting us to see how nature seems to support Nick’s conclusion. The rising sun, the jumping bass, the warm lake water juxtaposed with the chilly air: as we follow Nick’s perception of these things, we also feel his connection with the ongoing stream of life. Feeling that connection leads us to empathize with Nick in denial, even as we find it poignant. More generally, Hemingway turns the genre of loss-of-innocence narratives on its head by making “Indian Camp” a story in which the protagonist denies that he has lost his innocence. Paradoxically, however, the inferencing that Hemingway guides us through makes us register Nick’s loss even more deeply. We come away empathizing with Nick and admiring the artistry of his creator.

The beginning and the ending of A Farewell to Arms provide even greater opportunities to reveal what lies beneath the writing iceberg. Here’s the famous opening paragraph, which Burns and Novick reproduce via a nice variation of their usual pattern with Hemingway’s writing. Daniels reads the first sentence and then forms a duet with Edna O’Brien, who reads the middle sentences with him; Daniels then yields the floor to O’Brien who reads the last one. This strategy highlights the rhythms of Hemingway’s prose.

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving, and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves.

Cushman calls this passage a demonstration of “rhythmic mastery” that also “breaks all the rules” (no one before Hemingway would use “and” fifteen times in four sentences), and O’Brien suggests that Hemingway is applying what he learned about rhythm and repetition from Bach’s music to English prose. Again, good stuff, but let’s dig deeper by looking at material, treatment, and inferencing.

Material: nature in the form of the river, the plain, the mountains, the blue water moving swiftly in the river channels, the leaves on the trees; humans whose presence disrupts that nature.

Treatment: the first-person perspective of a soldier in the village, who, we learn later, is a young American called Frederic Henry.

Inferencing: Hemingway guides his audience to see more about the scene than Frederic himself does. More specifically, Hemingway invites his readers to recognize that (a) the causal connections between the presence of the troops and the disruption of nature—"the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees . . . and the leaves fell early that year”—and thus the general destructiveness of the war; and that (b) Frederic does not register those connections, restricting himself to his faithful recording of one thing after another. All those “ands” are crucial to this inferencing.

Similarly, later in the chapter Frederic does not seem to register Hemingway’s implicit association between the effect of the rain and the effect of the troops: “. . . in the fall when the rains came the leaves all fell from the chestnut trees and the branches were bare and the trunks black with rain.” By guiding his audience to see Frederic’s situation more clearly than Frederic does, Hemingway constructs Frederic as an unreliable interpreter of his own situation.

Hemingway then uses the last two sentences of the chapter to nail down this discrepancy between his audience’s inferencing and Frederic comprehension: “At the start of the winter came the permanent rain and with the rain came the cholera. But it was checked, and in the end only seven thousand died of it in the army.” Who says, “only seven thousand died”? Who confines the casualties of the cholera to those in the Allied army? A committed ironist, a military official trying to minimize casualties, or a callow young American volunteer in the ambulance division who has not thought much about war. Frederic does not qualify as an ironist, given the earnestness of his recording, and he is no military official.

In sum, underneath that stylistically brilliant first chapter, Hemingway invites his readers to infer how much innocence and naivete Frederic has to lose and how much he needs to learn about the war and the world.

In contrast to the Nick Adams of “Indian Camp,” Frederic not only loses his innocence and naivete but recognizes the loss. Indeed, he learns a lot about the war and the world from Catherine Barkley, who once tells him that she’s afraid of the rain because she sees herself dead in in it. (The issue of how Hemingway’s ideas about gender influence his construction of Catherine’s character is a complex one that I won’t get into here, except for a few comments below.) After Frederic makes his farewell to military arms, he and Catherine establish their own happy but fragile existence in Switzerland. That happiness is permanently shattered when Catherine dies in childbirth, along with their baby. Burns and Novick use their commentators to emphasize how much Hemingway struggled with how to end the novel after Catherine’s death—the ms. shows forty-seven different attempts! The documentary, however, does not address why the ending Hemingway chose works so well, and, thus, misses an especially ripe occasion to make visible more of what lies beneath the surface of his deceptively simple prose.

Material: what should the final part be? A philosophical reflection along the lines of the famous “If people bring so much courage to this world, the world has to kill them to break them” passage? Indeed, why not use that exact passage? Or should the narrative end with a line of dialogue? Or a report of Frederic’s actions in the immediate aftermath of Catherine’s death? Or something else?

Treatment: Once that choice is made, what’s the optimal way handle it? Should Frederic explicitly express his grief and sorrow about losing Catherine? Or should the emotion be suppressed? If suppressed, how to invite his readers to recognize it?

Hemingway opts for the report of a final action and treats it by returning to the style of the opening chapter: “Troops went by the house and down the road and . . .” becomes “I went out and left the hospital and walked. . . .”

Inferencing: The style is similar, but Frederic’s voices are radically different. The first chapter is in the voice of Frederic the naïve ambulance driver. The last sentence is in the voice of the enlightened man who feels Catherine’s absence and the destructiveness of the world in every fiber of his being but who is not himself destroyed by those feelings. This man now understands rain as a synecdoche for that destructiveness but who carries on despite its presence. As Hemingway matches voice to action, he invites his readers to recognize that, in taking these small steps back into the world, Frederic is not yet strong at the broken places but is deliberately (in both senses) advancing toward such a condition. The final sentence, then, though suffused with Frederic’s grief, also indicates the completion of his transformation from the unreliable character narrator of Chapter 1 to a character narrator wholly aligned with the perspective and values of his creator. From this perspective, Hemingway chose well among the forty-seven options he considered for the ending. We may cry, as Edna O’Brien did, in reading this novel, but we also come away moved by its aesthetic power.

After such responses, we may also want to raise questions or objections. Here are just a few. Does Hemingway, despite initially giving her a perspective aligned with his—and showing that she is one who is strong at the broken places—treat her as a disposable woman, important primarily for her service to both Frederic and his own artistic ends? Even as he transforms his experience with Agnes in his construction of the Catherine-Frederic relationship, does Catherine’s fate include a tinge (or more) of vengeance against Agnes? Does Hemingway overdo it with the emphasis on the world’s destruction and on his use of the rain? (Riddle: What’s Hemingway’s answer to “why did the chicken cross the road?” Answer: “To die. In the rain.”) But I would suggest that these questions become more intriguing when put into dialogue with the answers that emerge from a focus on Hemingway’s handling of material, treatment, and inferencing.

There’s a lot more to say about that handling in Hemingway’s other work, but I hope this much indicates how I’d go about saying it. I turn now to why I think the sculpted iceberg needs to include several holes.

The sculpture needs the holes to signal that the relations between the life and the writing can never be fully explained, and it needs more than one to signal that there are multiple gaps in those relations. The first, and perhaps largest gap, is between formative experiences and ultimate achievement. When Burns and Novick look to the life for experiences that help explain Hemingway’s famous style, they highlight such things as his extended childhood engagements with the music of Bach; his experience as a journalist for the Kansas City Star who insisted that their writers should: “Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English”; and his reading of Gertrude Stein with an eye toward her experiments with repetition and syntax. Influences, yes. Explanations, no. How many others played Bach, wrote short sentences and paragraphs, and read Stein, and how many of them became accomplished writers?

A second gap is between specific experiences and the transformation of those experiences into powerful fiction. A Farewell to Arms is based on Hemingway’s experiences in World War I, including his relationship with Agnes. But A Farewell to Arms is far from a roman á clef, and the departures from Hemingway’s personal experience are crucial to the success of the narrative, especially the different trajectory of the relationship between himself and Agnes and the one between Frederic and Catherine. Where do those departures come from? Not from other direct experiences, but rather Hemingway’s own imagination in combination with his sense of what the narrative needs. In other words, the transformation of experience into powerful fiction depends not just on the experiences themselves but also on the writer’s ability to see beyond the experiences to their significance. This transformation also depends on the writer’s sense, often intuitive but sometimes deliberately conscious, of how introducing something that departs from the experience can have ripple effects on the rest of the narrative. A third gap arises because writing is itself its own activity in which one learns by doing and in which what one learns has an existence apart from whatever else is happening in one’s life. How does one get to Stockholm for the Nobel Prize in Literature? Practice, practice, practice—and, to adapt what Michael Katakis says at the beginning of the documentary, be like “so many other people, except [have] enormous talent.”

In a sense, Burns and Novick devote six hours of filmmaking to unpacking Katakis’s description of Hemingway as such a man and to looking for connections between his fundamental similarities to so many others and that enormous talent. If I’m right about what stands apart between the life and the writing, it is inevitable that Hemingway succeeds more with the similarities than with their connections to that talent. Inevitable and perfectly fine because the life is captivating. Nevertheless, it’s the writing that fuels the interest in the life, and just how Hemingway was able to produce it will, I suspect, never be fully explained. What we can do, however, is continue to increase our understanding of what lies beneath its surfaces.