POETRY ROADTRIP: Detroit; “Obadike’s Armor and Flesh, and Madgett’s Lotus Press”

Poetry is a labor of love-no surprise there, but I hope what you find in this series of monthly articles will. As a poet myself, I often feel as if what I do has a small level of impact on the world at large, though schooling taught me the fact is irrelevant. Yet I know from my discoveries here, there are hundreds, if not thousands working along my side. This project is an opportunity to travel the country with my fellow travelers, poets and publishers who believe wholeheartedly in what they do and in the power of language.

Poetry is a labor of love-no surprise there, but I hope what you find in this series of monthly articles will. As a poet myself, I often feel as if what I do has a small level of impact on the world at large, though schooling taught me the fact is irrelevant. Yet I know from my discoveries here, there are hundreds, if not thousands working along my side. This project is an opportunity to travel the country with my fellow travelers, poets and publishers who believe wholeheartedly in what they do and in the power of language.

I began with a list of presses courtesy of the CLMP (Council of Literary Magazines and Presses). The goal, albeit somewhat whimsical, is to visit a press and a writer each month to find out what's really going on poetically across the country. I've never physically made it cross-country, so this literary "roadtrip" begins my virtual travels. The path will be winding, but with the goal of discovery in mind, I hope my journey will introduce you to something new and inviting around the bend, and put you in touch with good poets and good people.

This October we begin in Detroit (coincidentally where I was born, but I moved before I was two). Though trips have taken me back for Buddy's Pizza, my mother's favorite, Detroit always seemed like auto-town, not literary town. I didn't know that it is home of Lotus Press (and has been for over 30 years). The name of the press comes from publisher Naomi Long Madgett's reading of the Egyptian lotus. It is a metaphor about the poetics of African Americans-how being transplanted from Africa creates a new voice, thus, the press's motto: Flower of a New Nile.

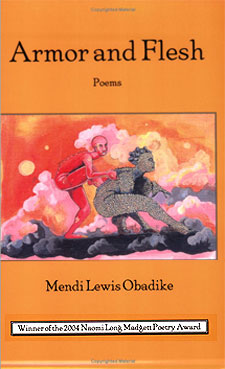

It seems fitting that Mendi Lewis Obadike's first book of poems, Armor and Flesh, the 2004 winner of the Naomi Long Madgett Poetry Award, is primarily concerned with issues of identity. Many of the poems discuss the dichotomy between internal and external selves, and play with the notion of duality of the self.

Lotus Press, Inc., May 2004, 61 pages, $12.00

Lotus Press, Inc., May 2004, 61 pages, $12.00

Though a few poems feel a bit adolescent, her debut collection probes the reader into remembering the past. She asks: how well do we know what it is like to be young, or a woman, or black, or essentially human? Lines like "Her speak is a seed in it" ("Tell Me This is Because We Remember Long") and "open can be a color between pink and brown" ("Open"), and the line breaks "tasting like prickly./ Stank./ We are naked and motionless" ("Something Burning") distort language and syntax so that we share in her precise discomfort as she creates a world that makes words and ideas feel new (much as they do in that period of self-discovery during the teens and twenties). She confronts her youth and attempts to locate who she is in relation to the world. The poems in this collection echo Elizabeth Bishop and I think of "In the Waiting Room," in which the young Elizabeth travels through reading a National Geographic, then returns to herself with new light. So too does Obadike take us to Santiago, Caracas, Atlanta, her childhood, essentially traveling physically as we move from external environments to those more personal and raw, the landscape of memory.

Recently, I was fortunate enough to speak with the heart behind Lotus Press, Naomi Long Madgett, age 83.

CS: What was the poetry scene like in the years preceding the founding of the press?

NLM: My second book was published in 1956, the year Dudley Randall returned to Detroit, but I didn't know him or of any other black poets in the city. It was a very dry period with few books being published nationally by black authors and no anthologies. The publication of my book was therefore such a rare event that it attracted a great deal of attention. Several feature stories about it were published in local newspapers, and I was invited to read in Grand Rapids and Philadelphia. Eventually I met Oliver LaGrone, another Detroit poet and sculptor and we became friends, often reading or being interviewed together on the radio.

The first extended visit to Detroit of Rosey E. Pool, a Dutch scholar living in London, served as a catalyst, drawing together other black poets who had not been aware of one another's existence. There were about eight of us who started meeting in one another's homes to read and critique our poetry. Then Margaret Danner came to Detroit and asked Rev. Theodore Boone if she could live in the house next to the Baptist church where he was pastor and use it for arts activities. The poets started meeting there, becoming known as the Boone House poets. We put on a very successful program at Hartford Avenue Baptist Church in which our group read. Boone House lasted from 1962 until 1964. After that, Oliver, Dudley, and I became a part of an interracial group; an anthology of our work, entitled Ten, was published. With the advent of several independent black publishing companies-Broadside, Third World, and Lotus, in that order-the publication of literature by black writers increased. Now there are so many black authors it's almost impossible to count them.

CS: So how did the press come about?

NLM: In 1972 I completed my fourth book of poetry, Pink Ladies in the Afternoon, and was looking for a publisher. Broadside Press was publishing chapbooks by such poets as Audre Lorde, Nikki Giovanni, and Etheridge Knight, but the mood of black poetry then was anger and rage against white people. That's what readers were looking for. My poetry didn't fall into that category. Also it was a full-length book, and Broadside was publishing only chapbooks. Broadside Press was lukewarm to it, and white publishers to whom I submitted, did not accept it. Three people who were interested in my work offered to pay to have the book printed if I would do the legwork. For that purpose, Lotus Press was established. After publication, the group did not publicize the book and it wasn't selling as well as it should have been. I felt I could do better on my own, so they agreed to turn over the remaining stock to my husband and I for a nominal amount. I didn't intend to publish more books, but I had a black student in one of my classes at Eastern Michigan University who was writing poetry. She would bring me her work to critique. I thought I could encourage her by printing a chapbook of her work, but I didn't know what I was doing and the page numbers came out all wrong; I had to throw away what I had printed and start over. It looked terrible, but she was proud of it. From then on, I learned by doing, so our books gradually improved in appearance. Then I met an elderly poet at a festival where we both read. I liked her work and agreed to publish her next book. Word began to get around and poets started sending me their manuscripts. We have now published and distributed about ninety titles, with me doing most of the work myself.

CS: How do you see the work of Lotus Press in the context of black poetics?

NLM: There is a great deal of interest today in performance poetry. I won't say that it is better or worse than literary poetry, but it's very different. Since Lotus Press is a publisher, our interest is in literary poetry. Our name stands for excellence; that is our only criterion for selecting poetry to publish. We are not concerned about subject matter or style as long as the poetry has literary merit. Therefore, there is a great deal of variety in the poetry we have published. Some is very political, some racial, and some is neither. I wasn't even sure Claude Wilkinson was black when he was judged the winner of the annual Naomi Long Madgett Poetry Award. Many of our poets have moved on to major presses and prestigious awards. I see myself as a ladder on which they can climb to higher exposure.

CS: How do you do it?

NLM: It is almost impossible for a press that publishes only poetry to exist long because most people don't read or buy books of poetry. I never expected to make a profit from publishing poetry; it is a labor of love and a service I provide for other poets. For years I kept it going with my own money. Eventually we received 501(c)(3) status so we could apply for grants and donations. It has been mostly donations from individuals that have kept the press in existence for 34 years. When I do readings of my own poetry and sell copies of my books, the money goes to the press to help sustain it. We could never afford a director, and what little help I have is volunteer. When we celebrated our thirtieth anniversary, eighteen Lotus Press poets came from all over the country at their own expense to participate in two days of readings. I took that as their way of expressing appreciation for the sacrifices I have made to get their work into print.

To learn more about Lotus Press, please visit: http://lotuspress.org

And for information on Naomi Long Magett's autobiography: http://wsupress.wayne.edu/africana/afrliterature/madgettpj/madgettb.html

And Mendi Lewis Obadike: http://blacknetart.com/sweat/sweat.html

Hope you enjoyed Detroit, Poetry Roadtrip Destination #1. Post comments as we go along --