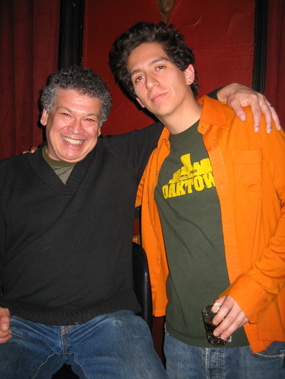

2.25.07: Daniel Alarcon & Francisco Goldman

2.25.07: Snowflakes were falling gracefully down on the quiet "Oscar Night" streets of the Lower East Side while the drinks were pouring generously inside the warm and cozy KGB Bar. Authors Daniel Alarcon and Fransciso Goldman packed the house with a crowd of friends and admirers abuzz with anticipation to hear them read. Daniel read a somber short story about a blind man's attempts to recruit a young boy to beg for him. After he read and the applause subsided, he took a moment to introduce his friend and mentor Francisco Goldman. With gentle, moving words and after a handshake and a hug, Francisco took us for a raucous ride reading from his novel The Divine Husband.

**This evening's reading will be available soon on podcast. Please stay tuned!**

**Subscribe to KGB BAR Reading Series podcasts in itunes by clicking here; or by copying and pasting:

feed://feeds.feedburner.com/kgbbarlive into your favorite podcast application (iTunes, Thunderbird, etc.) In iTunes, simply go to Advanced, then select "subscribe to podcast," and paste in the url above!

***FIND OUT ABOUT OTHER KGB BAR PODCASTS THROUGH OUR AUDIO BLOG OR AUDIO RSS FEED.

Francisco Goldman was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to a Guatemalan mother and Jewish-American father. His first novel, The Long Night of White Chickens (1992), won the Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction and was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award, and his second, The Ordinary Seaman (1997), was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award and The Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and was short-listed for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. He is the author of the novel The Divine Husband.

KGB: You spent some time as a journalist. Can you tell us a little bit about that, and how that affected your fiction writing?

Francisco Goldman: I went down to Guatemala to do my three stories for MFA programs. And I sent them out, and I got in, but also I got very lucky, and Esquire magazine bought two of them. Then I was at a crossroads: do I go to MFA school, or, well, I'm published now, but that wasn't enough of an excuse not to go, but Esquire offered me the chance to write non-fiction. So I said, yeah, I want to go back down to Guatemala, and write about what's happening there. I'd just been amazed. I didn't understand it. Despite my family roots, I was just like any sheltered American kid coming out of school, I didn't know anything. Even when I went down to Guatemala, and holed up and wrote my New York City weirdo love stories, which is what those first stories were, I was going, Jesus, what is going on down here? The revolution had just happened, Guatemala was in that very strange, horrific nightmare state, you know, dirty war happening in the city, lots of disappearances and murders, but none of it reported in the newspaper - the newspapers were censored - so I didn't really understand what was happening. And I went down and did my first piece in journalism.

KGB: Did you suggest that to Esquire, or did they suggest it to you?

FG: I suggested it to them. They said, what do you want to do? They wanted me to go to Nepal, for the travel section. I wanted to go to Guatemala. I didn't do any journalism for a number of years - about five years - and then in 1999, I published this piece on the Bishop Gerardi murder in Guatemala. I spent the next eight years - the whole time I'm writing Divine Husband - also reporting that story. That's the book that's going to be out in October, The Art of Political Murder.

KGB: So is the new book, The Art of Political Murder: Who Didn't Kill the Bishop?,going to be a collection of your reporting, or a book about your experience reporting that story?

FG: It's a chronicle of an investigation.

KGB: Daniel Alarcon said that your second book gave him permission - the freedom - to do what he wanted to do in his own work. Have you ever felt that way about someone else's work?

FG: If you're looking at Latin America, it was difficult. My particular generation - people born in the fifties - at that point in Latin America you'd see the boom generation and really admired that and really know that wasn't the way to go. You couldn't do magic realism, etc. What I learnt a lot from was looking at, really immersing myself, in Latin American novelists, and really looking at Americans of that generation, which was a whole bunch of writers, from Richard Ford to Saul Bellow - that strong American first person - and I had to find a way to fuse those two things. I think the person who - if anybody kind of gave me a real jolt and showed me how it could be done early on - it would be Salman Rushdie, in Satanic Verses. He goes and sets himself in immigrant London and ranges out, and plays with magic realist tropes and plays with that kind of rhetoric of the tropics, and then comes back to that firm - even if he doesn't really use first person, he uses first person in Shame, which also helped me a lot - but I think Rushdie was the guy who I most - cause he's not that much older than me - most identified with, early on, and probably helped me the most at that point. Him and Martin Amis. That kind of first person, which I used a lot in my first novel. You have to go out and lasso these different things, these societal things, and let the intimate voice go to war with them, with big storytelling.

Interview with Daniel Alarcon

Daniel Alarcon's fiction and nonfiction have been published in The New Yorker, Harper's, Virginia Quarterly Review, Salon, Eyeshot and elsewhere, and anthologized in Best American Non-Required Reading 2004 and 2005. He is Associate Editor of Etiqueta Negra, an award-winning monthly magazine based in his native Lima, Peru. A former Fulbright Scholar to Peru and the recipient of a Whiting Award for 2004, he lives in Oakland, California, where he is the Distinguished Visiting Writer at Mills College. His story collection, War By Candlelight, was a finalist for the 2006 PEN/Hemingway Foundation Award. He was recently named one of America's Best Young Novelists by Granta.

KGB: We expected you to read from Lost City Radio, but you didn't; what were you reading from, is it a new collection?

Daniel Alarcon: I probably have maybe half a collection done. I've been reading from the novel so much recently that I'm just kind of bored with, so I just decided to read a story.

KGB: What's the difference for you between working on your stories and working on your novel?

DA: I like novels better.

KGB: Why?

DA: You have a deeper relationship with your characters. You get to know them over the course of three years instead of three months. Everything about is deeper and closer and it's a long-term seduction instead of a quick one.

KGB: I noticed that both in the excerpt you read from today, and in some of the stories in your collection, you use city as character.

DA: It's something I'm always fascinated by, the way that urban areas impose their identities, or the way the multiple inhabitants of one urban area will co-create an identity. That's something that's always fascinated me, partially because I was born in Lima but I didn't have the opportunity to grow up there - I grew up in the suburbs of Birmingham, Alabana - so all of my trips to Lima were shocks of urban chaos that for me, as a young man, was incredibly, incredibly exciting. Not even as a young man, a young boy - you know, 8, 9, 10, going to Lima, going to school in Lima, everything about it was so exciting and so much more exciting than where I was living the rest of my normal life, that even then in certain ways, Lima was part of my imaginative life. And there's something about not being from a place that allows you to really look at it with clear eyes. And now I sort of consider myself from Lima, not from Lima at the same time, and I like that insider-outsider position.

KGB: You did your undergrad in anthropology. How did that affect your writing and your thinking about fiction?

DA: All of the tools of an anthropologist are tools that I use. I don't write about myself, I almost never write anything autobiographical. Anthropology training teaches you to observe, to understand people's story in context - social context, cultural context, historical context - and I've always been fascinated by that place where journalism, literature, and anthropology meet. It's the area that Kapuscinski inhabits. That's what I want to tell. I don't write memoirs. I don't like autobiographical fiction. I don't want to write about, you know, my relationships or whatever people write about. It's much easier for me to write about other people, listen to them and hear them and take their stories and mix them with my emotions and make them up and do whatever I want with them and out comes something.

DA: All of the tools of an anthropologist are tools that I use. I don't write about myself, I almost never write anything autobiographical. Anthropology training teaches you to observe, to understand people's story in context - social context, cultural context, historical context - and I've always been fascinated by that place where journalism, literature, and anthropology meet. It's the area that Kapuscinski inhabits. That's what I want to tell. I don't write memoirs. I don't like autobiographical fiction. I don't want to write about, you know, my relationships or whatever people write about. It's much easier for me to write about other people, listen to them and hear them and take their stories and mix them with my emotions and make them up and do whatever I want with them and out comes something.

KGB: So you just go to bars and buy them drinks and get people to tell you their stories?

DA: Or they buy me drinks, and then they just want to talk to me.

KGB: What are you working on now?

DA: I'm working on a bunch of things; a bunch of stories, and something that will hopefully become a novel, but we'll see.

KGB: Last question. What football team do you support?

DA: I'm life-long Alienza Lima fan. I'm an Alienza Lima fan because my dad is an Alianza Lima fan, and because all my cousins are not.

-- Jamila-Khanom Allidina, KGB Bar Lit Intern