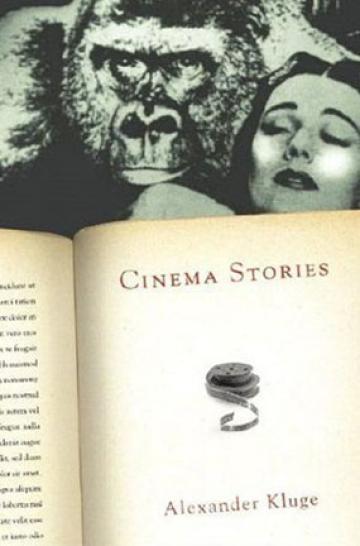

Alexander Kluge's CINEMA STORIES

New Directions, September 2007 | 96 pages, $11.95

Alexander Kluge is a German author, filmmaker, and the founder of Ulm Institut fír Filmgestaltung, the institute that birthed New German Cinema. As the recipient of Germany's highest literary award, The Bíchner Prize, and four Gold Lions from the Venice Film Festival, "accomplished" doesn't begin to cut it. Sure, he's well respected, but he's earned more than respect from his friends, who represent the acme of European intellectual life: Theodor Adorno, who first encouraged Kluge to explore film, and Fritz Lang both counted him among their inner circle. Steadfast, multifaceted, prophetic- Kluge deftly cross-sections culture in service of exposing its inner realities, or, to quote the slogan of the French progenitors of film, the Lumiere Brothers, "apporter le monde au monde." Through artifice, be it filmic or literary, he holds a mirror to the world where it seems more like itself. At 75, he shows no sign of slowing down. This fall, a MoMA retrospective and the Venice Film Festival will both celebrate his life and works. Concurrently, his book Cinema Stories is coming out from New Directions.

Cinema Stories is a bold, galvanizing hybrid of fiction, interview, film theory, German history, scientific inquiry, and his cosmology of cinema. It's also a tabloid that exposes the secret hopes of those ignored by the spotlight. Stars in their respective fields such as Rem Koolhaas, the architect, Olive Thomas, the first casualty of the silver screen to be exploited by the media, and Leon Trotsky, each contribute to his cobbled ground of discourse.

The book itself stems from one man tapped into multiple mindsets. Likewise, Kluge understands the core of film to be comprised of side-by-side 'texts.' Let me try to condense this theory: every other 48th second of a film is completely dark. The text we see transmits light, image, and meaning. The dark text conveys a nonconcious thrust toward the next instance of light, image, meaning. The human brain incorporates this polyphonic stream of dark and light through a complex sequence of "misunderstandings" that, according to Nobel Prize winning neurologist Professor Eric Kandel, "fit together [...] so that the brain (even if it does it with a fallacious text) reproduces the outside world [...] against its will." The dark phase draws the mind into a dream-like or drug-induced state of completely self-created signs and signifiers. Cinema Stories transports the reader into a similar state, though the matrixes of signs are prescribed meaning by an expert guide-Kluge.

Kluge portrays cinema reeling from a skein that reaches into outer space and inner cognizance. The resultant dream-reality is produced by the mind's uncanny ability to suture apparently irreconcilable opposites. Kluge's acrobatic text likewise mines contradiction for truth, beauty and coherence.

In the "Notes" section of the book, Jean-Luc Godard is quoted as saying, "Children, when they are born, / and old people, when they die, / don't talk, they see something." To which Kluge rejoins, "If you were to cut yourself open would a child come out?" Likewise, Kluge implies that if the human mind were cut open the cosmos would come out. And if the cosmos could be reproduced, it would be an endless reel of moving images. Cinema Stories boasts enough intelligence, insight, and flexibility to project that reel onto the reader's psychic screen just long enough to believe that cinema is so beloved precisely because it mimics eternity.

In closing, I'd like to quote from the namesake of the Bíchner Prize, George Buchner-from his novella, Lenz: "Only one thing remains, an infinite beauty passing from form to form, eternally unfolding." With a kind of erratic, casual brilliance, Kluge arrests and presents for the reader this unfolding beauty he finds manifest in film.