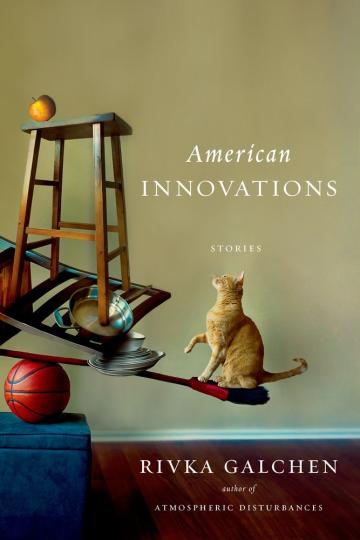

AMERICAN INNOVATIONS: Stories by Rivka Galchen

“It was my life that was lying in the middle of my life like that, like a pole-axed wildebeest.”

American Innovations (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), Rivka Galchen's first short story collection, could be described as an exercise in scrapbooking the psychological 'state' of the union. The stories are titled with language borrowed from of the shelves of corner stores--grandiose newspaper headlines, gaudy candy flavors, celebrity obituaries (“The Lost Order,” “Wild Berry Blue,” “The Late Novels of Gene Hackman,” to name those profiled in this review) which then gets put on trial against the backdrop of emotionally charged, sometimes deeply private, sometimes even iconic spaces of American life.

The collection's opening story, “The Lost Order,” glimpses (what initially appears to be) the lawless empire that is the mind of a woman newly unemployed. In it, the narrator--previously an environmental lawyer--spends idle days hidden away in her apartment as a 'daylight ghost.' She focuses her energies (in short fragmented bursts) on domestic miscellany that looms newly large--the pursuit of "not making spaghetti," the complexity of getting dressed, the phantom pressure that moves her to answer a misdirected phone call and take a customer's lunch delivery order. Upon first glance, the thoughts and events that succeed in seizing the narrator's scattershot attention seem like perfectly arbitrary passerby in easy agreement with the story's title. As they pile up, however, a subversive common denominator surfaces, revealing the passerby as orders in disguise, which all come--either directly or indirectly--from men. Eat yogurt instead of spaghetti because a brother no longer “recognizes your legs”; Cook chicken for a man on the other end of a misdirected phone call; Spend the afternoon searching for a husband's lost wedding ring. Order has not been lost but has simply changed hands to a time-worn, invisible standby.

“The Lost Order” introduces the underlying questions that haunt every story in American Innovations: What are you left with when the evidence of 'having a life' in America dissolves while you are still living? Do you have any say in who you become? And who--if anyone at all--might that be?

Over the course of the collection, Galchen considers these questions with ambitious dimension, and from wide-ranging angles and ages. “Wild Berry Blue,” arguably the most tenderly written story in the collection--is the inverse operation of “The Lost Order.” In it, 'a life' overwhelms a young girl's blissfully shapeless days. The narrator (the young girl) falls in love at first sight with Roy, a McDonald's employee and recovering heroin addict who addresses her as “little sexy.” Before falling in love with Roy, the young narrator has what the narrator in “The Lost Order” has irretrievably lost--ownership over her idling: “Beautiful, Horrible: I had a running mental list. Cleaning lint from the screen of the dryer--beautiful. Bright glare on the glass-- horrible. Mealworms--also horrible. The stubbles of shaved hair in a woman's armpit-- beautiful.” Over the course of the story, this landscape of holy clear-eyed-ness drains from the narrator as she obliviously pays it forward--across a fast food restaurant counter--for fixes of Roy's attention, transactions which--not unlike those made by a drug addict--leave her with a “[lost] appetite for certain details in life” replaced with an “an overcrowded and feverish empty.”

In “The Late Novels of Gene Hackman,” Galchen moves the question of “having a life” to “an “overcrowded and feverish empty,” realized--a writer's conference at Secret Paradise hotel in “humid, and sleepy and closed” Key West. Galchen's protagonist, J, the young writer invited to this conference is granted a plus one and guilts herself into inviting her widowed stepmother, Q, a Burmese woman whose latest business venture--an Online Vitamin Hall of Fame--recently failed and who is usually either talking about losing weight or her friends in the hospital. Upon the pair's arrival, J conjures Key West in the way that it is typically conjured by literary cynics-- focusing on its snazzy daylight ghosts--convertible-owning, blue drink-toting, young be- girlfriended retirees, and aura of Art Deco lifelessness--its wealth of “aboveground graveyards that look like “ambitious papier-má¢ché projects that school children had put together. Except that [in Key West] there were no children.”

However, by indulging the tired lifeblood among the walking dead stereotype, J--as the reader ought to expect Galchen to orchestrate by now--sets herself up for derailment.At the dinners and parties surrounding the conference, J cannot locate a conversational point of entry amid the anxious talk of aging academics--Twitter as the end of literature, the counterintuitively hopeful condition of having numerous tumors. Meanwhile, to J's bewilderment, Q (who is not accustomed to mingling with the ivory tower crowd and who initially did not want to attend the party before losing weight) is thriving. Ghosted, J surrenders to the smug, default position of writers at a loss for words at parties--the wallflower wired for sound. But she does not get away with this for long. An 87-year-old writer of post apocalyptic fiction from whom J had previously tried to excuse herself spots J and calls her out on her cliched aloofness: “I know about young people. They're very conservative and judgmental...You think we are all decayed and dying, which we are, of course, but you're dying everyday, too. You'll just keep dying and dying. I know from my own children.” She took a sip from her little blue drink. “I mean look at you. Quiet as a superior little mouse.”

In a sense, it is as though this character is talking back to Galchen, herself, her own creation calling her out on the audacity of commenting so comprehensively on what it means to “have a life.” In a country in which neither career daylight ghosts nor Mickey Mouse enthusiasts, nor the people deploying those stereotypes are safe from “accumulating moments of being nothing,” where does one even begin to judge? American Innovations leaves the reader feeling stunned in every sense, a constructive state of overwhelm, but also one which might inspire a trip to the corner store, for another fix of that wild berry blue.

Rivka Galchen received her MD from the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, having spent a year in South America working on public health issues. Galchen completed her MFA at Columbia University, where she was a Robert Bingham Fellow. Her essay on the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics was published in The Believer, and she is the recipient of a 2006 Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers' Award. Galchen lives in New York City. She is the author of the novel Atmospheric Disturbances.

Maggie Beauvais is a freelance writer and Assistant Literary Events Editor for Slice Magazine. She lives in Brooklyn, NY, is good with babies, and takes unreasonably long walks.

Maggie Beauvais is a freelance writer and Assistant Literary Events Editor for Slice Magazine. She lives in Brooklyn, NY, is good with babies, and takes unreasonably long walks.