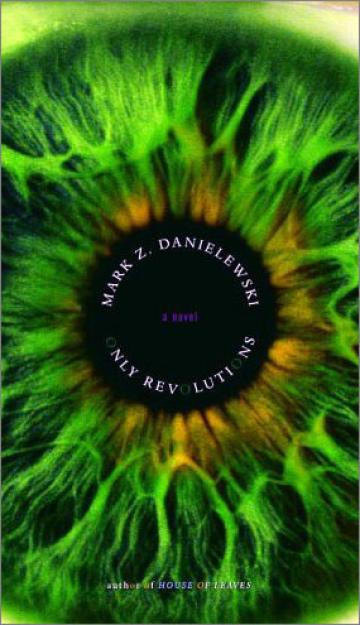

Mark Z. Danielewski's ONLY REVOLUTIONS

384 pages, $26.00

Mark Z. Danielewski's Only Revolutions is two books in one, or two books that make a third: a road novel to be read left to right in the voice of Sam, and, once upside-downed, right to left in the voice of his girlfriend Hailey. Both Sam and Hailey are, in Danielewski's all-encompassing, all-the-time language, "allways sixteen," and they ride as "US" through the United States and its history, from the Civil War to the near future, in a succession of incarnations, guises and vehicles, through a score of adolescent adventures. Their accounts of these, set opposite each other on the page (so presented to overtake one another at the middle of this circular book's 360 pages, each of them half-circling with 180 words), are margined by scrolling factoids that recount history-large, top-down history-contemporaneous with their intimate roadtrip. What else? These alternate-alternate realities are all told in a mock epic poetry, an updated "Song of Ourselves"-a Whitman-homage that reads like a cross between a Transcendentalist tract and Hallmark "Roses are Red."

Here's Sam on the road:

I mosey on. Diverging all amblingwith every step. Trailblazing.Nothing but freedom ringing with protest.Bringing unrest.

Here's Hailey on their sexlife:

Impulsively I headwork his lap, teething his shaft a rashshuck for the gobblurt I lobfast to the dirt.

Here's Hailey again:

We continue on our travels, slippingrods for catalytic meltdowns, misfirescoughing US along on shreddling tires.Rippp, prahp, hisssssh. Three more flats. Even with my Leftwrist Platinumy Twist.Past Carbondale and onto Waterloo.- I'm happy with you, I abruptly shout. Soooo happy.

I should mention that every instance of the letter "o," as in the circular first letter of the first word of the book's tire-tired title, is printed in a different eye-color, Sam's and Hailey's: alternately green and brown. Needless to say, more will be said about this book than it deserves, both good and bad. Not as much a novel as an object-actually, it's a miracle of book design-it seeks less to pleasure and inquire than to overwhelm in idea and awe in execution. Danielewski's experimentation asks not what the next story is, but how next or newer to tell an olden story; or, perhaps more preciously: how to tell the story of how to tell next. In this mode, Only Revolutions could have been a reunion of Finnegans Wake, but instead it's an unmade Dennis Hopper film with two unfinished and yet sober, Ph.D.-dissertation-ready scripts. To be sure, Danielewski tests the reader not only physically (the publisher recommends you read eight pages left to right, then eight more right to left), but also intellectually: he is saying, make your own sense, your own road down these roads. This is philosophically admirable (an enactment of what's better left to the speculations of critical theory, making a hardcopy of hypertext's Internet promise) but real-time, real-life tedious, especially because the poetry of the book, its rhyming, enjambment-happy prose, is more punny than funny, and so affectedly rhetorical as to be parodic of the freewheelingness it, in theme, is so earnest about.

When a book like this is criticized it's usually done in a foolish, self-important defense of an older (or just old) conception of the novel, a Victorian narrative strike against the encroachment of the experiential, the object-focused open-work, or the technological innovations of the Web, the Babel-collaborative. To be in favor of the new, though, is not to be in favor of the mediocre, or the merely interesting, unless one is a masochist, an academic, or both. Borges wrote about labyrinths because to write a labyrinth is abhorrent. Kafka's The Trial is not a legal document. And Beckett's lifework might be about silence, but is not, as it exists, silence itself. Danielewski is an extremely resourceful and highly creative artist, but what he needs if he's to make the masterwork he's so conceptually prepared for is a little of that revolutionary verity: a story, and a prose, equal to his antic strictures and structures, his palimpsests and poesy.

Mark Z. Danielewski was born in New York City and now lives in Los Angeles. He is the author of House of Leaves.

Mark Z. Danielewski was born in New York City and now lives in Los Angeles. He is the author of House of Leaves.