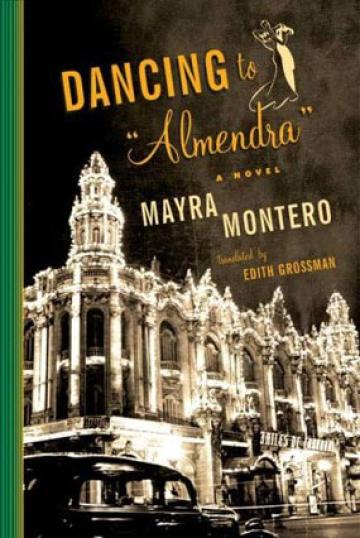

Mayra Montero's DANCING TO "ALMENDRA"

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, January 23, 2007

272 pages, $25.00

Deep down we know that every work of history is a work of fiction: most often a portrayal of a past in which the writer did not live, sometimes a rendering of an event that the writer only perceived in part. Yet history fascinates us in a way that literary fiction does not. There is a sense of solidity in a work of history that we cannot shake, no matter how often we remind ourselves that every text is an invention, that no work is a window into the way things were. History, if only because it attempts to depict events that really happened, arrives with a weight that literature strives to assume.

It is the tension between these two fictions, history and literature, that makes Mayra Montero's eighth novel, Dancing to "Almendra," unsettling, even startling. The book is based on Montero's research into the mafia activity in her homeland a half-century ago; her narrative tells of a fictional young reporter's investigation into the murder of a prominent Cuban mobster in the fall of 1957. History and literature collide in this novel. As Montero's protagonist, Joaquín Porrata, attempts to unravel complicated mob dealings in Havana and New York, he runs into Charles "Lucky" Luciano, Meyer Lansky, George Raft; he attends the opening of the the Capri Hotel in Havana, he visits the Park Sheraton in Manhattan, and he glimpses the barbershop where mobster Umberto Anastasia really was killed.

Though we have seen such collisions between history and literature in many books before - from the novels of Flaubert to those of Fuentes - they have not ceased to entrance. The premise is too compelling: one fiction framed by a very different kind of fiction; history as seen through imagined eyes; the past as dreamt in, and for, something as brazenly fake as a novel.

Montero is particularly adept. She creates these collisions with an eerie grace, and an elegant perversity. How alien, how absurd, how bizarre is this young reporter's Cuba! When Joaquín first glimpses Lucky Luciano, the gangster appears "Chinese," he smiles "as if he were Chinese, with an enigma playing around his lips." Joaquín walks in on Meyer Lansky listening to sentimental songs in his boxer shorts, looking old and sad, though the mobster also has "the nipples of a newborn" and "a cloud of talc" floating around him. Joaquín meets a Havana zookeeper so obsessed with George Raft that he insists his friends call him by the names of Raft's film characters, and he witnesses the zookeeper's surreal encounter with Raft, when the actor wonders if he has met his Cuban double.

It is unfortunate, then, that these collisions are the novel's only captivating moments. When Montero's narrator focuses on the intricacies of Cuba's criminal activity or on his personal life - when history and literature do not directly intersect - the novel feels uninspired, even insipid. It is hard to stay interested as the young reporter sorts through the mob negotiations surrounding the opening of the new Havana hotel; these are the mob politics of a half-century ago, and the mobsters who suffer the most, financially or physically, Montero keeps to the margins of the narrative. And as the young reporter's investigation starts to strain his relationships with his friends and family, he discovers only that the city where he has spent his life has "an imaginary face, more or less its everyday face...and another hidden face, the face of landings, of secret transmissions, home-made bombs, and disfigured corpses on sidewalks" - a discovery that has been made about many cities in too many other novels.

Still, it is a gift to see people who once lived through eyes so fresh. In Montero's novel, the past is sporadically strange, frightening, and pathetic all at once - as complicated and ambiguous as our own lives appear to us.

Mayra Montero is the author of eight novels and a collection of short stories. She was born in Cuba and lives in Puerto Rico, where she writes a weekly column in the newspaper El Nuevo Dia.

Mayra Montero is the author of eight novels and a collection of short stories. She was born in Cuba and lives in Puerto Rico, where she writes a weekly column in the newspaper El Nuevo Dia.