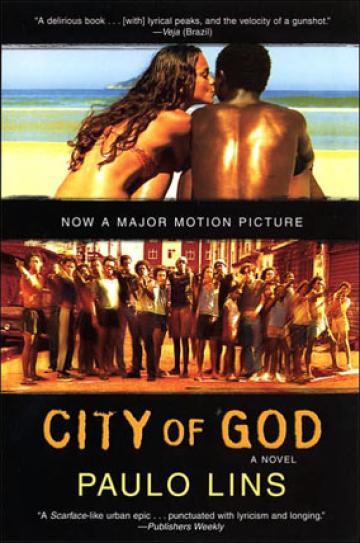

Paulo Lins' CITY OF GOD: A NOVEL

Grove Press, September 2006

448 pages, $15.00

The characters in Paulo Lins' City of God have developed immunity to the world. They are capable of killing without batting an eye. This absence of love creates a desire so horrific it sometimes leads to an intolerable jealousy: a man brutally kills the baby his wife has with a white "northerner," another digs a grave for his philandering wife before he murders her, and yet another kills the husband of the woman he lusts after when she tells him she will only consider dating him once her husband is dead.

The divisions within the City of God, the housing projects outside of Rio De Janiero, are clear. Conflicts between distinct groups magnify the violence. There's the separation between men and women: "Perhaps if he cried too, something at the core of him would change, but men didn't cry, especially in front of women. Men who cried were queers." As well as racial separation: "He enjoyed killing whites, because whites had stolen his ancestors in Africa to work for nothing, whites had made favelas and stuck blacks there to live in them, whites had created the police in order to beat up, arrest and kill blacks." Noticeably, there is the separation between rival gangs and the hierarchy of the drug dens.

But there is human emotion beneath the hard skins of City of God residents. Even though they seem accustomed to violence and loss, they can still be moved by it, as seen in the stories of the corrupt cop Boss of Us All and the transvestite Ana Flamengo. Boss of Us All is more disturbed when his wife leaves him than he is about the gang troubles that he can't control. "His wife had written to him saying she wasn't coming back to Rio de Janeiro. She was tired of that life of deaths. She refused to sleep any longer beside a man whose weapon was an extension of his body." A stranger mistakes Ana Flamengo for a vanished lover and she is happy to play the role. After two weeks the stranger disappears, "Then it was just her eyes searching for her knight in shining armor in every car like his that drew close [...] She'd never felt so distressed."

We hear these stories from three different perspectives: Hellraiser, Sparrow, and Tiny. Their narratives span over twenty years, beginning with Hellraiser's story in the '60s when the City of God was built as a refuge for flood victims, and ending with Tiny's story when the violence was at its peak in the early '80s. The boys seem like similar versions of one another: each is wrapped up in drugs and murder. Occasionally, there's hope for a quieter life, but it is quickly extinguished. Within their narratives, the boys' voices are lost in the stream of overpowering violence. The only purpose the repeated murders serve is to drill the society's chaotic rhythm into the reader's mind.

In the world of the City of God the physical reigns and emotions are suppressed: "He'd become aware that the only physical space that belonged to him was his body. He had to preserve it." Yet, many of the characters' lives end in bloody death. Only the last line grants the reader a reprieve from its intensity: "It was kite-flying time in the City of God."

Paulo Lins was born in Rio de Janeiro and at age seven moved to the 'City of God', where he was raised. He escaped the cycle of violence there to become an internationally celebrated writer. He still lives in Rio.

Paulo Lins was born in Rio de Janeiro and at age seven moved to the 'City of God', where he was raised. He escaped the cycle of violence there to become an internationally celebrated writer. He still lives in Rio.