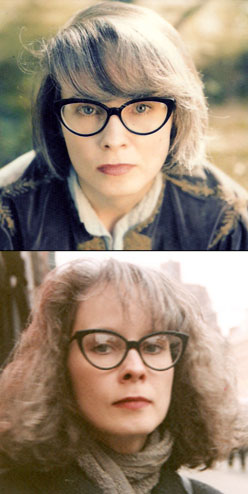

Form and Decay: An Interview with Mary Gaitskill

Mention Mary Gaitskill, and people start thinking about sex. Until her 2005 novel Veronica, Gaitskill was perhaps best known for her short story "Secretary," about a girl, her boss, and a spanking, which was Hollywood-ized into a 2002 love story starring Maggie Gyllenhaal. The movie is now every twenty-something straight boy's favorite sex flick without an X-rating, casually dropped into conversation and Nerve.com personal ads as shorthand for softcore kinkiness. Although it's impossible to ignore the originality and deftness of her prose, the easy association between Gaitskill and dark sex turns some people off. "I like her writing," said a friend once, "but it always seems like someone's getting beaten up."

But titillations or turn-offs are only part of the story. The miracle of Gaitskill's prose is in her attention to bodily experience, the way her writing plays with the undulations of the physical world screened through the mental. Veronica is told from the viewpoint of Alison, an ex-model afflicted with hepatitis and walking, for a large portion of the book, through the forest as well as the wilds of her own mind. In her meanderings she finds her old friend Veronica, from New York, a woman "precious and proper" who eventually dies of AIDS.

In September, Gaitskill came to Seattle to read at the Bumbershoot Festival. After her reading, she sat down in the Pacific Northwest sunshine to answer some questions for KGB Bar Lit.

Bess Lovejoy: I wanted to ask you about your use of pity as a transformative force. You said in another interview, "We strut around like we're a big fucking deal, but we're all to be pitied." I found your use of the word pity really interesting, because we're often taught not to pity people, because that might make them feel shame. I was always raised with the idea that you can be empathetic...

Mary Gaitskill: Or compassionate...

BL: Right. But don't pity people. Can you talk about that, what you think about pity?

MG: If you look it up it a dictionary, "pity" is almost defined as compassion. But I use the word because it's more powerful. I understand what you're saying, that sometimes it can be seen as a form of condescension, and often people don't like to be pitied, but to me pity is a more visceral response. Compassion is a very good thing, but there is a certain distance in compassion, it's a more mental response. It's in a cooler register. Pity is a more viscerally overwhelming feeling, and in its nature more involving. If you were onsite right in the aftermath of Katrina I don't think you'd be feeling compassion, I think you'd be feeling something a lot more powerful. It wouldn't even be an issue whether you were looking down on people -- those kinds of distinctions wouldn't matter. And I think that pity is a very profoundly human emotion. I'm not saying therefore it's always wonderful -- I don't like to feel pitied myself, and when I feel pity for another person there's often a lot of other things mixed in with it -- but I think it can be simply a very profound feeling of outrage and horror at the state of another person's pain.

BL: In Veronica, you suggest pity can make us more human.

MG: Certainly, animals don't feel it.

BL: Yeah, they just devour each other or do whatever they're gonna do. [Laughter].

BL: So how did Veronica begin ... was it a single image? What was the germ of the idea?

MG: There were a couple of things. A very good friend of mine got sick. AIDS came as a great shock to people during the '80s. We had sort of forgotten you could die from a sexually transmitted disease. It seemed like a medieval outrage. And there was a very interesting juxtaposition between the reality we were forced to face and ... what I was seeing around me with people wanting to perfect who they were, their physical bodies, their lives, how they thought they could control things.Also in the early '90s, people were just obsessed with models in a way that I'd never seen before. I mean, people have always admired models and found them fascinating in some way, but not the way it was in the '90s. The way it was in the '90s ... was kind of grotesque, really. It was like suddenly there was nothing higher that a girl could possibly be.

BL: I was going to ask about models.

MG: They were so paramount as cultural icons at the time. It was something that certainly seized my mind.

BL: During the recent reading at Bumbershoot, you were talking about the particularly American focus on healthy attractiveness as normal, and the alarm or sense of outrage people feel when something goes wrong, as though it's an injustice somehow to be sick. You also read about an old woman [in a new novel-in-progress], and how there was a certain softness coming through her, in her decay. Yet we so often see decay as ugly. I'm interested in this idea that there is something beautiful in the patina of age.

MG: I don't think of age as a patina, I think of age as breaking a patina. It's the youth that's the patina, and it gets cracked. There's something about the elegance of the human form that's quite awe-inspiring sometimes ... when you see a very beautiful person, not necessarily a model, just a very beautiful, elegant person, or aside from physical beauty, when you encounter beautiful, elegant speech, very beautifully formed ideas, very gracefully expressed thoughts, art. That falls apart too. The mind decays, the ability to express oneself decays, and there's a way in which you give way to the vastness. It's like you're this small container, and when that begins to crack, it's horrible in a way because you don't want yourself to crack, but on the other hand, you become helpless before something more awesome.

BL: Is that the softness, becoming helpless?

MG: You could say that's part of it. When I say softness ... it's like in Veronica, when I describe how Alison is walking and she sees leaves crushed on the ground, becoming like a paste of decomposition. I find that really beautiful. It's soft because it's losing its form. Form is very defined, and when the form starts to break up it becomes soft because it's losing the hard edges of its definition. Though of course I find form and definition beautiful too.

BL: I'm also interested in your use of music, this idea of living in songs. In Alison's case, what she really wants to do as a young girl is live in the music, which seems to fade as she gets older. Is that something you've experienced, or you think a generation experienced, or do you see it specifically as part of Alison?

MG: A little of both. When I was growing up music was really a powerful force, and I don't get the sense that it is as much now. I'm not sure, because I'm not 15, and so I don't experience it the way 15-year-olds do, but when I was 15, 16, 17, there was a sense that music was describing a reality that was more powerful than the one we saw around us. I don't know how to talk about it without being completely cliche, and they were cliches, and it was nonsensical in many ways, but there was a sense that music was a liberating force, that music could end the war in Vietnam. I'm remembering the lyrics to a particularly ridiculous song by a local band in Michigan -- rock ' n roll music is all that you need to be free. I don't know if anybody literally believed that, but there was that feeling in the air, that music was that powerful. And one of the things that makes music powerful even now is that when you listen to music with a group of people, it can give you the illusion that you're experiencing the same things as those people. It really gives a sense of a shared emotion in a way that reading doesn't, even if you go see a reading together. Music penetrates much more quickly and much more viscerally, so there's an illusion of a tribal quality to it, which I think people felt really strongly in my generation. We were the first generation that experienced electric music ... it was louder and more aurally intense than it had been before.

I don't know if anybody literally thought they wanted to live like music, and even for Alison, I don't think she would say she really rationally believed that was possible. It was just a feeling. The music created this wonderful romance that seemed very new, and very palpable.

BL: And you don't think that's around in the same way anymore?

MG: It doesn't seem it to me, but again, I might perceive it differently if I was younger. It seems a little cheaper now because it's so everywhere and it's used for so many different things. When I was younger there was the phenomenon of music being used to sell products, but not as much, it was pretty uncommon, and it was kind of like our music, it was something that you felt could be rallied around. Now it's something that can be attached to all kinds of things. Which is possibly the more realistic way to look at it.

BL: I wonder if you can talk a little bit about what you're working on now.

MG: I don't know if I can say much about it. I've decided ... I was talking, during the reading, about how I developed a facility for talking, but I've become a little suspicious of that facility, because I think in a way it's quite superficial. I think the truth is you don't entirely know what you're doing. I'm most immediately working on stories. This novel -- I don't know how long it will take for me to do -- it's quite difficult for me right now.

BL: How long have you been working on it?

MG: I started it in 2000. I worked on that and Veronica simultaneously. Not literally at the same time -- I'd work on Veronica for six months, then this one for six months, and then Veronica. I think of this one as called "Bettina" because the main character name is Bettina, but it won't be titled that. It's about a middle-aged woman who's working at a paper that used to be a kind of prestigious weekly and is now a giveaway, and she is having a lot of doubt about her life, and what it's been about and what she's stood for.

BL: Where is it set?

MG: New York City.

BL: When you Google your name, there's an interview that comes up from 1994, in which you talk about how you often begin your writing with just a physical image or a phrase. Does that still hold true?

MG: Sometimes, not always. Veronica was a more distinct and character-based idea. I do have some stories that come out of a particular ... this is gonna happen and then this and then this, and it's click, click, click, it kind of fits together ... but sometimes it is just an image or something somebody said or something that happened to me. The book I read from did [begin with an image]. I was thinking about Bettina anyway, but the thing that made it click in my mind was an image ... of the weather personified as human beings. And I have no idea why that has to do with anything in the book, but that's how it came to mind.