Morgan Entrekin on Publishing, Partying and Promoting

It was the hottest day in New York in over fifty years and the legendary Morgan Entrekin, president and publisher of Grove/Atlantic, seemed right at home in the heat. His slight accent, ease and civility felt not just the byproduct of his fine upbringing, but characteristically Southern; his directness, quickness of speech and love of diversity, on every level, betrayed his Nashville roots and underscored his inner New Yorker.

I was eager to speak with the man who published, promoted and partied with some of the greatest authors of our time, and to understand how Grove has managed to survive – and thrive – in a publishing world that is increasingly conglomerized.

In his expansive nearly floor-to-ceiling windowed office, books, books, and more books lay on every conceivable surface, floor included. He wore a blousy button-down faded blue shirt made of the finest cotton that matched his grey blue eyes, and pale yellow linen pants. His face bore a resemblance to a child just woken from a reverie: calm, contented and receptive. He sat behind his desk. I pulled up a chair, and from my vantage point, gazing at him over the teetering stacks of papers, I was fairly certain our conversation would turn into a farce of “What? What did you say?” so he politely suggested another seating arrangement. “I'm comfortable in any chair,” he said, rising from his desk and settling down in a chair next to me. This seemed absolutely true: his body was at ease, yet his mind was active. I felt in the presence of a man who had trained himself not just to look at, but also within and beyond whomever or whatever was in front of him, and then to assemble and situate his observations in a larger context. An assessment? Of sorts. My assessment: prodigiously intelligent and yes, virile. But his hair! Where went the infamous ponytail, the bohemian bob?

I remembered from my research that Morgan had attended Montgomery Belle Day Academy. The very conservative all-boys' school on which Tom Schulman, a classmate of Morgan's, based his book Dead Poets Society.

Suzanne Dottino: Did you have to wear uniforms?

Morgan Entrekin: No uniforms, but they made us cut our hair.

SD: Which I see you have again!

ME: First time in 35 years. I wore my hair long because I wasn't allowed to then.

SD: What were you like back then?

ME: I was engaged politically in Civil Rights, a student leader – a proponent for change since thirteen. I created a bit of a stir in that mid-size community. It was an interesting moment coming of age in the South – Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam. I was 13 in 1968 – I was old enough to experience it. I didn't participate but I certainly was socially aware and conscious – that formed the rest of my personality and who I am.

SD: Tell me about your family.

ME: I come from a wonderful family. My parents were supportive of me in discovering things on my own. My father came from Georgia. My mother's family had lived in Tennessee for many generations and they were prominent. She was active in politics, in civil society. My mother was very active in the arts, and with the Woman League of Voters. (...the organization's name seems to be League of Women Voters...) My father was an attorney and had great interest in the arts and music. I grew up in a, I wouldn't say liberal . . . an open minded, not your traditional conservative southern household. I was surrounded by art and music. My father was one of the early patrons of Red Grooms; in 1973 we got a series (of Red Grooms paintings) called No Gas Café – my mother had the ceiling gilded in gold, and painted the walls black with Red Grooms on the walls. That was pretty intense.

SD: Very. Were they also big readers?

ME: Everyone. My Father, before he became very successful with his law practice, bought a library from an estate sale – he was a book lover from way back.

SD: Dinner table conversations must have been very interesting in your household.

ME: It was a very intense time. There was this whole generation gap, which sounds ancient, the concept of it, but people old enough to remember know, that there was a very serious divide between a lot of members of the greatest generation and the boomers, the 60s, the counter culture. In my house, there was never that gap, my parents were open minded, liberal. I guess you would say my father was more independent in his politics. My mother was more traditionally liberal. They were definitely perceived as liberals in Southern Society, but highly respected.

SD: What were you reading then?

ME: Early Kurt Vonnegut was a big hero of mine all through high school. Richard Branagan, Faulkner, Hemingway and Fitzgerald.

SD: Being so imbedded in the South, why did you choose to go to Stanford?

ME: That was a pretty big jump. It was 1973, I was mesmerized by San Francisco – the counter culture – most people my age at the time were, it was the place that was the center of it (in hindsight, had I been more informed I would have gone to Berkeley).

SD: What was your experience of it?

ME: I fell in with a group of writers like Scott Turow, Max Crawford, Chuck Kinder, Richard Hugo, Raymond Carver – an interesting range of writers, none of which at the time were well known. Ray couldn't get published.

SD: Did you want to be a writer?

ME: I wrote some, I didn't have a burning desire to write – I wasn't someone who had been somebody who wrote all my life. And I don't have a brilliant talent as a writer. I like the Dorothy Parker quote: “I like having written.”

SD: Did you aspire to be a publisher?

ME: Total serendipity. My [college] classmates were mystified by Radcliff (publishing course), being Westerners and outsiders, so far from New York. One of them, I don't remember which, we were having beers and he said, "Well, go and if you want to write you can get great contacts, and if you don't you can help us." In those decades you didn't grow up with as much awareness of the process of media. Like I didn't know of where books came from. Two or three imprints that I had awareness of because of what they presented were: New Directions, Fiction Collective and Grove Press.

SD: Who was the most interesting writer you have worked with and what was great or challenging about that?

ME: The most interesting writer I have ever worked with has to be Kurt Vonnegut. Kurt was a hero of mine when I was growing up in Tennessee in the late 1960s and early 1970s. When I got the opportunity to work with him as a young editor at Delacorte Press in the late 1970s I was tremendously excited. That experience, coming so early in my career, is one of the things that kept me committed to publishing.

SD: Could you describe the literary scene when you moved to New York in the late 70s – and your participation in it?

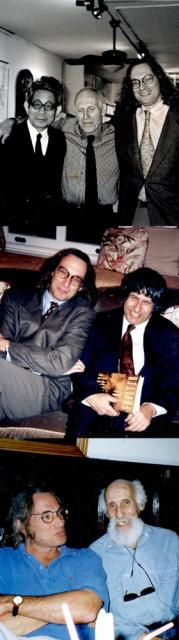

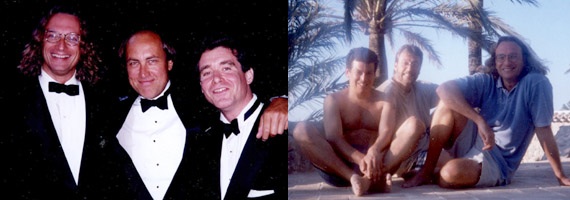

ME: I had a great time for many years. The literary scene was just a part of it. I had a great appetite for life and had a lot of adventures. One of the great things about NY is that there are so many different scenes—uptown society, downtown bohemian, the art scene, the music scene, Wall Street people, the Saturday Night Live scene—I moved among all of them. The late 70s and early 80s were great years. I went from the early Studio 54 to the Mudd Club to the Odeon and the SNL and art crowd to Nell's—and of course East Hampton and Long Island. I met an incredible range of fantastic people. It all seemed more innocent then. People weren't hanging out for a living. You could find a club or bar or restaurant and there would be an interesting group of people hanging out and it wouldn't all be written up in New York Magazine or Page 6 within 15 minutes and ruined.

And there weren't party promoters. I was doing it all for fun but it ended up being helpful for my work. I knew a lot of people and it all fed what I was doing. The literary scene can, like any scene, get very claustrophobic. I never limited myself just to that. There was more of an old-fashioned literary scene though—at Elaine's, at George Plimpton's apartment—and I spent plenty of time at both places. New York is a fantastic place to be young and in a creative business. There is so much to do and discover. So many adventures to have. And I did as much as I could. I probably went out 5 out of 7 nights week for 10 or 15 years. My advice to young people in NY is to go out and move around as many scenes as you can. There is a lot of chaff but there are so many great and interesting people to meet. Go to readings, art openings, parties, anything.

SD: How did you meet and Michael Tolkin and acquire The Player?

ME: I met Michael upstairs in the Mike Todd room at the Palladium nightclub at a party for Richard Ford in maybe 1987. I was introduced to him by Michael Daly, the journalist, who is an old friend. Michael told me he was a screenwriter but that he was writing a novel. About a year later his agent Flip Brophy called and said, "You are never going to remember this but about a year ago you met a screenwriter"—and I cut her off and said yeah, his name is Michael Tolkin and he is writing a novel. I read the manuscript and bought it and the rest is history.

SD: When you reflect back, what about those years do you miss most?

ME: The constant sense of adventure and the possibility of surprise every day. . .

SD: Is the publishing world any worse for this loss?

ME: Less fun. A lot less money. I prefer it the old way, but I don't like change, for the most part. I mean, there are some things I want to change, but I don't really miss those years. I am glad I enjoyed them while they lasted but I am happy to be where I am now in my life.

SD: And then the publishing houses started to conglomerize.

ME: In the mid-to-late 60s, Gulf & Western owned Simon and Schuster, RCA owned Random House. The book business was just becoming divisions of multinational media corporations and yet there were still some old fashioned cottage industries, gentlemans' business, whatever you want to call it, those methods.

SD: How did Seymour Lawrence influence you?

ME: He was a model in that he was working within this environment of the larger corporate group but yet had an old fashioned, entrepreneur and independent sort of impresario role. I also worked on some commercial books which was good training.

SD: How many books do you read in a week?

ME: Well, I work on about twenty-five books at a time. I mean I am looking at these books. I am also reading to evaluate.

SD: There is a lot of pressure put on a second novel, more so if the first one sells well. You have a closer relationship with your authors than most publishers, how do you approach an author who is under the gun to produce a second novel of equal if not better results?

ME: You build up your energy to write your first book. To motivate yourself you have to believe it is going to make a difference. The act of writing a novel is so difficult financially, psychically, socially, etc. I try to set people up not to be disappointed by saying, ‘Look, name me three or four of your favorite authors—Toni Morrison, Richard Ford, Richard Price, and James Irving—none of them sold five thousand copies of their first books.' Their first books came out and it didn't change their lives and they didn't go on Oprah – the fact is that it doesn't happen most of the time. It doesn't happen to very fine writers. And if you set yourself up as the media so frequently does, it only focuses on these big advances only on those big successes. I think it perverts people's expectations. What I try to do is to manage their expectations by saying, "Go through this experience, if we sell six or eight thousand copies, you've doubled the amount that John Irving sold on his first book – is that so bad?" As a publisher I try to be optimistic but you also have to be realistic. That is the key thing.

SD: That must be a hard balance to maintain.

ME: I am disappointed sometimes by my books, but I am also more realistic than the authors because I've been doing this for almost 30 years and I've published over 2000 books and I've been through it and what I think can be very debilitating to that author and crippling for that second book is that their expectations are artificially inflated either by themselves or by their agent, or their publisher or their friends and then when the book comes out and they get the reviews they say, “Is that all there is?”

SD: The reality seems, to me at least, that if an author's second book doesn't do well, it is very, very difficult for them to sell a third. Publishers are unforgiving.

ME: That's a whole other long bad situation that we're in because there is less continuity in the relationships. It used to be, the old model was; we are going to publish these younger writers at a small level, we're going to grow their audience for them and then hopefully we're going to have the “breakout book.” Now the idea is, the first book is the breakout book: the first book because you have two things: you have no sales track on the computer of any of the booksellers – no sales track means the publisher can position it usually at a good level – and the other thing is that you have media interest in a fresh new face.

If it doesn't work out – you have a problem, either the major booksellers national chains or independent bookstores, they look at their computer and they say, “We took ten or five thousand or whatever of the last one and we had to take 60 percent back and that wasn't a positive experience for us, and therefore we are going to be cautious of what we are going to do, if it starts to sell, we'll order some more.” You end up at a disadvantage in a large conglomerate. That's a very tough story to tell your boss who is making the financial decisions. And you've lost the personal relationship of the commitment that a publisher, an individual, made to an author with the idea we are going to do this over time, we are going to partner to together. Build together.

We [Grove] have managed to survive through hard work, passion, the support of a great group of authors, a little bit of luck—and an extraordinary backlist. The backlist not only gives us a steady revenue flow but also helps attract other authors and helps position our books with booksellers, reviewers, foreign publishers, etc.

SD: Tell me a little about Black Cat.

ME: In the last five years it has become very difficult to sell literary fiction in hardcover. We were publishing some books as original trade paperbacks but I wanted to do more. I decided that we should revive the Black Cat imprint so that we could have a focused publishing program for these books. It is working very well. We have published over 35 titles and a very high percentage of them have worked. The great thing is that everyone feels so much more positive about the experience—the author, the agent, the bookseller, and of course the publisher. And the books are staying in the stores—and backlisting—so that an author has a chance to develop a readership. I definitely think this is the trend of the future and we will continue to build on the success we have had with Black Cat. The audience is anyone interested in good books—fiction, narrative nonfiction and memoir, and literature in translation.

SD: What are some tough decisions you have to make?

ME: Toughest thing is when you get a book you don't really like, and are not very enthusiastic about.

SD: You must have been through this experience over and over again over the years.

ME: And I still believe that is the toughest decision that I face as a publisher. I ask myself, What do I do? Do I tell the author the truth? Do I publish the book even if I am not enthusiastic? If you look at almost any significant writer over time — they wrote some clunkers.

SD: How do you manage it?

ME: In principal, I believe that I am partner with that writer and we ought to publish every piece of work they do and I also believe that I ought to be candid with them.

SD: What if an editor is hot on a book and you're not?

ME: It depends on which editor it is, what their track record is, and how much money it is going to cost. If it is a small amount of money – I'll probably let a young editor take a shot — once. But I make that clear for them – I'll let them buy something once, and if it doesn't work, it is going to be harder for them the next time, so they be better be very sure this is the one they want to take a shot on.

SD: What do you look for in an editor?

ME: Enthusiasm, intelligence, someone who gets along with people – that is very important in a small company. I look for someone who is a self-starter – I need someone who is proactive, out there looking for things, going to readings – reading small magazines, not just waiting for Binky Urban or Andrew Wylie to send them the new hottest thing. Because we're probably not going to be the person who is paying the highest amount of money to get that thing. I look for diversity in taste.

The four fiction editors here besides myself are: my partner Jamie Bygn, Elisabeth Schmitz who is Charles Frazier's editor, Amy Hundley who handles translations, and Lauren Wain.

SD: What do you and your editors look for when acquiring a book?

ME: Good example is Winkie by Clifford Chase. Lauren Wain came to me with that and I liked the idea. It is so difficult to sell relationship or character driven fiction these days. If it has a little bit of hook it makes it much easier for me to take it to the outside world and convince the media, booksellers. I liked the hook: a teddy bear comes to life and is accused of acts of terrorism. As several reviewers have said that is an unfair simplification, but it works, it gets people's attention in ten seconds.

SD: What are your feelings on memoirs in light of recent events – or even before that?

ME: I'm still leery of memoir. We published This Boys Life. We have not had anything since then that has been that successful. I must confess: I don't read memoir myself very much, I would rather read narrative nonfiction, history, biography, current affairs, or investigative journalism, so as a result I don't feel confident about my ability to evaluate them.

SD: Have you acquired any memoirs that you are excited about?

ME: We just bought a book that is coming out this winter The Royal Nonesuch – by Glosgow Phillips, a young author who published a novel (Tuscaloosa) in his early twenties and now he is in his thirties. He works in the underground film industry and is a great representative of his time. Black Cat is publishing this. I feel we'll have success with this one.

SD: What do you think will become the lasting trends in publishing and how do you see Grove/Atlantic responding to those trends?

ME: I think there will be a growing market for books from around the world. Grove has always been committed to publishing international literature. I think there are more and more writers producing wonderful work from all corners of the globe. We will continue to search out and publish those authors and hopefully find an audience for them in the US. I also believe more books will be published as trade paperback original.

SD: How do you feel being the last of the rock star publishers?

ME: I don't think I am the last—there is Jamie Byng of Canongate in the UK (and he is our partner in Canongate, US) and Richard Nash of Soft Skull. And there will, I hope, be others to come.

SD: What do you most want to take away with your legacy?

ME: I would like to think we published a lot of good books that contributed in some way, and that we did it with passion and integrity and had some fun.

SD: What do you have coming out now that you are excited about?

ME: Michael Tolkin's The Return of the Player—this is a great novel about Hollywood and Los Angeles and contemporary America by a very successful screenwriter, director, and novelist. Michael is brilliant and this book is going to get a lot of attention. You may remember the Robert Altman film made from the first novel The Player. Ancestor Stones by Aminatta Forna—a truly beautiful novel about women in West Africa. Alligator by Lisa Moore—a fantastic young Canadian writer—the book was a finalist for the Giller Prize and won the Commonwealth Prize for Canada and the Caribbean.