KGB Bar Homecoming Feast!

When Dr. Pat Zumhagen returned to the States from six months in Paris studying photography last year, she came back in one of the worst times of the Covid’s devastating effects. She had been hearing stories of how particularly hard-hit small businesses had been and how many were closing never to open again. Pat was especially alarmed that one of her favorite bars and literary institutions, the KGB Bar on the lower east side of Manhattan, might be among the casualties.

Pat had a long history with the KGB bar, which Denis Woychuk had founded in 1993 in a former Ukrainian Union Headquarters. She first became acquainted with Denis and the Bar when her son, Brian Zumhagen, had a book party there to celebrate one of his recent translations. From that point, Pat became a devotee and enjoyed musical and literary events with Denis, who was to become a close friend.

During these years, Pat taught at Teachers College/Columbia and most springs she taught a course entitled Cultural Perspectives: New York City Literature. Denis would visit the class, adding his ample knowledge of the literary scene in New York especially lower Manhattan and sharing his own place in promoting some of the best writers of today. They would also use as one of their texts for the class samples from the KGB Reader, five volumes of which had been published of works that had been read at the bar. Pat’s class, following The New Yorker magazine as a model, would write their own “New York” stories and were given a night at the KGB to read from their own literary creations, thus joining the ranks of the literary giants who had read there, often early in their careers.

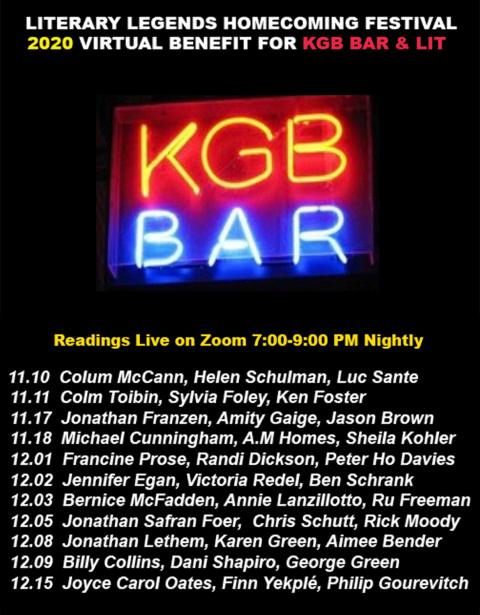

At the point when Pat returned from Europe, says Lori Schwarz, KGB Program Coordinator, the Bar had gone from being closed completely for seven months to allowing 10 people inside and closing at midnight. By December, the ravages of the post-Thanksgiving surge of Covid had brought new restrictions of closing at 10 pm and they were expected to be closed down completely once again. No outside activities were possible, as the bar is on the second floor. The picture for sustaining the bar was bleak. So Pat was determined to find a way to support and hopefully save a place and people she cared deeply about. She proposed to Denis and Lori the idea of a Literary Homecoming Festival where early readers, many now famous, would return to read via Zoom, and the “audience” or attendees would pay a nominal fee to watch and listen (Adults $18 and children $12.00). Never has there been such a bargain! Pat offered to organize the entire event, reaching out to and procuring the writers, planning the dates, and co-hosting the event by orchestrating the “Q and A” from attendees and managing the conversation among the writers with the backdrop of the KGB Bar shining virtually behind her.

The thing that Pat says surprised and delighted her the most was the enthusiasm and readiness with which writers responded. “Yes, yes, yes! We’d love to return to the KGB Bar and read for this event! We LOVE the KGB Bar and have such fond memories of reading and attending others’ readings there!” Pat shared that Jennifer Egan, determined to help, agreed to fill in on December 2, despite a commitment, as outgoing president of Pen America, to attend the group’s year-end celebration and dinner held earlier that same evening! Egan came and read from her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, A Visit From the Goon Squad.

Having attended most of these events in the moment, and now having listened to all of them multiple times, I can only say that it might have been called the KGB Homecoming FEAST, because that is what it is! Food for the soul, the in-person-event deprived, lovers of poetry, short stories, essays, and novels longing to revisit favorites as well as be introduced to new works.

With Lori co-hosting and expertly managing all the technological and marketing aspects, and Denis being on hand to welcome old friends, the Festival took shape and became a reality during the months of November and December, 2020.

The Homecoming Festival debuted on November 10, 2020, with three amazing writers, all of whom had read in the early days of the KGB bar and all of whom had appeared in the first literary collection edited by Ken Foster called the KGB Bar Reader. Helen Schulman, the kick-off reader of the Homecoming Festival and who had read in 1993, commented, “So thrilled to be part of this series at a great New York City literary institution!” Her sentiments were echoed time and again by all of the participants who remembered so fondly their days at the KGB Bar, which soon began to have readings almost every night highlighting various genres from poetry to short fiction and on weekends providing a venue for MFA Program students to try out their work.

Another reader on the opening night, Colum McCann, began by saying, “I actually feel like I’m in the KGB Bar, the way you enter up the stairs, smoke coming up from outside, a buzz coming from inside, and it’s packed, and there’s an energy in that space that is unrivaled by any other reading space I’ve ever been.” “What you have established is truly extraordinary,” McCann stated and said he was “willing to sign in from any place and time all over the world to keep the KGB going and the literary world it created.”

And so the series began! And I can say they were all truly, as Lori Schwarz once said, “magical.” But having been asked to write of a few highlights, here in no particular order, are some evenings that stood out for me.

Although many of the individual Q and A sessions brought some stimulating questions, one of the most truly captivating aspects of the Homecoming Festival was the conversation that occurred among the writers when the last writer had read. This dialogue among writers often about the how, when, and why of writing and its meaning in the world began on the very first night.

In response to a question about the structure of his most recent novel, Apeirogon, (2020) Colum McCann said, “Novelists are not as intelligent as people want them to be. A lot of the time I don’t know what the hell I’m doing, I’m operating on a wing and a prayer. Just hoping that I get the right note, like a musician. Content dictates form and its character and language that are important. You begin to see this container that you have created. and then the container begins to contain 100 stories, then 565 stories. . . and it is a kind of paying homage to 1001 Nights.”

Luc Sante, another reader that first night, quoted Louis Sullivan, the famous architect, that “form follows function.” “I began as poet, but I write in prose… but always potentially everything is flexible, it can go any which way, depending on the subject. Sometimes, it can be fun to plug yourself into a pre-existing form… But left to my own devices, I like to chop things up. I like to make contrasts, because I’m also thinking of film, of cutting away.”

Helen Schulman jumped in with “There’s a lot of math in my writing,” and for me— form girds me—so it helps me figure out how to process my ideas. Form gives me a kind of map. I don’t count pages but I weigh them. Readers often, although they may not know it, need the comfort of some kind of pattern, of repetition—I know it helps me to have some kind of musical pattern, and then I can fit things into form.”

“That’s beautiful, Helen, it’s all about that, finding the human music,” responded Colum. “A lot of writers are secret mathematicians or architects and may not know it. Weighing symmetry, emergence. . . It’s all about putting your finger on the music—the way the stuff sounds in the end. And that’s why a verbal reading series, like this one, is so important. It’s terrifying for an author, but also vivifying.”

In response to a question about how “difficulty and confusion” can operate in a work such as his current novel, McCann says, “The most important words we can say right now is ‘I don’t know.’ In this political climate, we are in a disease of certainty. [We need to] Embrace the messiness. This stuff is messy. We can get back to the original idea that we contain multitudes. How can we become so much more than one thing? Kaleidoscopic. I think we can do it through literature. We can scuff these things up. And at the fundamental core of all this, teachers and libraries and institutions like KGB keep this fuckin’ stuff alive.”

Pat closed out this first evening by saying that personally she “enjoyed every single minute,” a sentiment shared by me and everyone, I am sure.

Another night of engaging readings followed by thought provoking conversation occurred with Amity Gaige, Jason Brown, and Jonathan Franzen on November 17th. All three writers had also read at the KGB Bar in the first years of their careers, including Franzen’s reading from The Corrections, which became a #1 New York Times Bestseller. Behind the scenes, Pat confided, Franzen was very helpful in suggesting readers for the Festival and volunteering to come back on the spot to fill in when there was a fear of someone not being able to get there.

One of the definite highlights of the whole series was listening to Amity and Jonathan read together from her script taking on the voices of a husband and wife struggling with their marriage. As Amity had imagined, it worked beautifully to distinguish these characters with a different voice and made the story come even more alive.

One question that all three writers engaged with was the issue of veracity in their work and how important the research—journalistic and electronic searches—was to their writing. Jonathan remarked that “Truth is good. Writers are in the truth business—or should be. You’re really trying not to get things wrong.”

But the larger questions, of writing about experiences you have not had and how authentic one can be in recreating those experiences. For Amity, it means talking to people who have had those experiences and then trying to experience some measure of that reality. So setting a novel on a boat sailing around the world, when you’re not a sailor and never have been, she begins by speaking to those who have ventured on long sailing trips and then fictionalizing their actual experiences. She believes writing about things that are beyond her experience is a way to keep learning, an “excuse to expand my own life.”

Amity spent ten days aboard a boat in the Caribbean in heavy weather—"it was what I needed to write the book,” even if she wasn’t that happy to have that experience. “I’m afraid of sailing!” she confided. In some ways it was “madness” to set a novel on a boat.”

The very next night yielded another combination of writers who seemed to enjoy engaging with one another and gave the audience a lively, often joyful and thought-provoking evening. November 18th featured Sheila Kohler (first person to say “yes!” to Pat’s invite to participate in the Festival!), A.M. Homes, and Michael Cunningham (and a cameo by Johnny D, longtime legendary bartender at KGB, to introduce A.M. Homes). These readers were all published in the first KGB reader and read as far back as 1994. Interesting note: Cunningham’s initial story in that reader was “Mister Brother,” referenced during this Homecoming reading, by Denis Woychuk, who professed great love for that story. Cunningham responded by attempting locate a copy of the story as an add-on reading that night. Unfortunately, he was unable to locate a copy on the spot. As luck would have it, however, he agreed to allow us to publish it in the issue that you are reading right now! Check the lead fiction story!

After their individual readings, the conversation between Cunningham, Homes and Kohler moved to take up a very current topic of our times, “How do we/can we represent or tell the stories and experiences of “others,” whether that be the voice and thoughts of another gender, race, or generation?”

Sheila, recalling first what fond memories she had of reading at the KGB Bar and how electric the atmosphere was, read first there from her novel Cracks, published in 1999, which was turned into a movie, and was also included in the first volume of the KGB Reader. This night she read from a new novel called Open Secrets, which has a “crime thread” or mystery, as much of her writing does. The section she reads is of the thoughts and feelings of a fourteen-year-old named Pamela and this provokes a return to the conversation from the previous night about how one writes from another perspective—adolescence in this case "seemingly so authentically” as one attendee commented. “Well, I am interested in adolescence. And I remember it, maybe because I never really grew up. And I have adolescents in my life; I have grandchildren.” She also reads to her family to see how they respond to the adolescent voices she creates.

Michael Cunningham also talks about how he approaches writing about young people by thinking in terms of perceptions—how does THIS particular adolescent (for example 9-year-old Bobbi in his short story “White Angel”)—see the world? “I try to imagine the way this 9-year-old would imagine his world. The language comes from that.”

A.M. Holmes, in response to a similar question about imagining other’s experiences, remarks, “I’ve always been interested in shape shifting, the notion of psychologically how we evolve and how we inhabit others.” But, she reflects, “We are in a very particular moment right now where often people think they can only write about their own personal experience. That makes me very anxious.”

“Political correctness right now is to not attempt to inhabit the ‘other,’” she continued. But “trying on that which is unknown” is part of the creative and intellectual risk that she encourages her writing students at Princeton to take on—and more importantly, to risk failure. Homes feels, “If [they’re] not risking failing, then they’re not going to become the people they have the ability to be.” But often, if students have been successful and they’re at a university they worked very hard to get into, they become “risk adverse” and find it difficult to challenge themselves—to take creative and intellectual risks and “walk that tight rope because it can be terrifying.” If we’re only writing what we know, where is the challenge?

“Who has the right to what stories?” surfaces again when one attendee mentions the brouhaha surrounding the book American Dirt, about a Mexican mother trying to escape cartel violence and bring her young son to America. When publicity focused on the author, Jeanine Cummings, as a white woman with no direct connection to the refuge experience, there was criticism as to its authenticity and its use of “stereotypes, one-dimensional characters, and a white, American perspective.” Cunningham commented, “It crossed some lines that made some people uncomfortable. There are some lines—but where do we draw them? The first question I believe [writers should ask themselves is], “Do you feel /or to what degree do you feel you can enter the mind/body/soul/heart –of somebody not you? I feel there are characters very unlike me that I could write and some where I wouldn’t feel comfortable. I do not feel I could do that authentically. I could not put on their clothes—I have to be comfortable writing from that perspective. [It’s]Very loaded right now.”

A.M. Homes added, “Obviously, the imagination is wildly important, but we also have to make space for people who haven’t had a chance to tell their stories. And that’s a big piece of it. Allowing for those and the world of publishing [making space] for those who haven’t been represented yet.”

This issue was raised again in the memorable conversation thereafter dubbed as “the one that no one wanted to end” on December 3– women’s night– featuring writers Annie Lanzillotto, Ru Freeman, and Bernice McFadden. Issues of justice and literary representation were among the topics.

The last evening of the Festival featured Philip Gourevitch, Finn Yekplé and Joyce Carol Oates. Rebecca Donner, editor of the 2nd KGB Reader, On the Rocks, joined for this evening to introduce Gourevitch and Oates, who had stories published in that reader.

On this last night, Oates read from a piece she had written in April, 2020, during the early days of the pandemic and of quarantining. She describes a feeling of being “unmoored” from her usual procedures and routines and unable to “settle.” It is interesting that while many people felt the freedom from social engagements opened opportunities for perhaps creative and relaxing activities, many writers, used to being stationary and solitary, may have experienced this time differently. In her essay, “My Therapy Animal and Me,” Oates mentions the writings of Thoreau and Pascal and their proclamations about living outside of civilization as perhaps ultimately generative, but Oates feels that these are “fantasies a lot of us might have had, but when we actually have the experiences of driving life into a corner, the reality might be quite different.” She says, “Almost no one I know, no poet or writer, none of us—has felt this has been generating or a fertile experience. If anything, we write less and like what we do write less.”

Sylvia Foley, audience member and a writer who had read with Ken Foster and Colm Toibin on an earlier evening, responded in the Chat space:

Thank you too for speaking to the difficulty of writing/making art during pandemic times, how writing (the very lifeblood) suddenly doesn’t seem to have a place, or maybe it’s that one needs to completely retake its ground . . .

Anyway, thanks for your truth-telling.

What tales and stories and musings might come after this Pandemic subsides we can only at this time imagine. Maybe there are generative thoughts percolating just below the surface that will be nurtured when the anxiety and fear begin to leave us. I think of the cicadas about to emerge after 17 years underground. Who knows how they have been developing? But hopefully we won’t have to wait that long for these wonderful writers to draw from these experiences.

No stranger to writing on adversity, New Yorker Magazine contributor Phillip Gourevitch, known for his prizewinning coverage of the genocide in Rwanda and its aftermath, ended this evening and the series with a short story, stimulating yet another memorable post-reading conversation among writers and attendees. This one addressed the interrelationship of fiction and non-fiction and the ways fictionalizing can even be an aid to a reporter by prompting an examination of his own personal responses to an unexperienced situation, and fostering an emotional connection with subjects and their conditions. An amazing end to a rich literary experience at the KGB.

And on a last personal note, it was wonderful to see Finn Yekplé reading on the last evening, the youngest of the Festival readers at 17, but one who too made his debut at KGB Bar many years ago at the tender age of perhaps nine. Finn addressed the question put to him, “When did you decide to become a writer?” with a wry smile and said he didn’t think he’d “decided that” but raised a question many have struggled with. What does it mean to be a writer? If it’s someone who’s shared in any forum their creative thoughts and spirits and contributed to our way of imagining and interrogating the world, then indeed, yes, Finn, you are a writer.