In the Very Air We Breathed

Contents

- Preface • 4

- Introduction • 6

- “In the Very Air We Breathed” • 13

- Epilogue • 81

- References • 97

Preface

In 2001, at the age of 73, Maritza graduated summa cum laude from New York University with a double major in Art History and the Humanities. Even though her formal schooling had ended at fifteen when Nazi Germany occupied Budapest, she had been admitted to the University on the strength of an entrance essay she had submitted, “partly as a lark,” she has told me, when she chanced to hear on the radio that NYU was accepting “alternate experiences.”

Her thesis, entitled “Art and Artists of the Holocaust: Survival and Resistance,” opens with this description:

It was a cool November morning in 1944; we were a contingent of women of all ages, being marched to a slave labor camp. The early sun penetrated the mist and cast strange shadows, the fields were barren except for an occasional sunflower patch. The petals of the flowers matched the color of my yellow star. I promised myself to come back some day with my camera and catch the magic of this light. I now know that this ability to observe and reach within myself, the insistence of holding on to my identity and autonomy helped me to survive and was essential to my eventual escape.

In this passage we get a glimpse of the woman who was a keen observer, possessing a creative and courageous mind, determined to imagine a life beyond the horrific circumstance she found herself in.

In “Jewish Response to the Holocaust” another paper she wrote as a student, Maritza explores the concept of resistance and documents the multiple forms of resistance that Jews exhibited before and throughout the war. She extends Bauer’s1 definition of Jewish resistance as “any group [italics mine] action taken” (27) to “any act taken by an individual Jew to save his life or thwart a Nazi plan.” Maritza and other family and friends survived because of small and large acts of resistance, including, in her case, escaping from the death march that would have ended her life.

How did I come to know this remarkable woman, whose courage, ingenuity and foresight, as well as her determination to maintain her humanity in the most inhumane conditions continues to be an inspiration? Here is how our friendship began. 5

Bauer, Yehuda. The Jewish Emergence from Powerlessness. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, ©1979

Introduction

One [wo]man’s experience may serve as a point of entry into one of the most appalling human tragedies of this century.

— David Cesarani, Genocide and Rescue: The Holocaust in Hungary, 1944

Life may not be the easiest, but now, as always, I can find pleasure and beauty in it.

— Maritza Shelley, email March 25, 2016

As a young woman in her late teens, I would often ride my bike into the small village where I lived on Eastern Long Island, New York, and down the main street toward the ocean. I would sometimes stop at a beautiful stucco Episcopal church that had two tennis courts behind the pastor’s rectory. I would stand outside the fence, watching the same group of people who played for hours every morning. I was an outsider, not only to the game, but to the cultural connections that in many ways bound them together.

All of the players were owners of second homes, many highly educated, and several had grown up with considerable wealth and privilege. In most ways, their lives in no way mirrored my own. I was growing up one of six siblings, with parents whose formal education had ended when they graduated high school. A grandmother also lived full time with us, my two sisters and I shared one bedroom and my three brothers lived in our basement. In all ways our lives were modest.

These tennis players, however, were a very friendly lot, and would engage me in conversation, and one day, invited me to play with them. Even though I hadn’t played much tennis, they were so encouraging that I accepted their offer and showed up the next day in ragged cut off jean shorts over a yellow leotard with an old wooden racquet I’d found in our basement. I’m certain they were appalled but would never have even subtly suggested that I might don tennis attire. (Eventually, I made myself a white piquet tennis dress—and the fuss made over me the day I showed up in it made me realize how I looked beforehand!)

So began my decades long friendship with a group of people who profoundly affected my values and views of the world, those quite different from my Republican, largely agnostic family and conservative community. They were all liberal, non-religious Jews with leftist leanings, active politically and socially, and they nurtured those instincts in me. All had lived through the Second World War in various capacities and in various countries, including Poland, England, Holland and Hungary. Now they lived in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens and had summer homes in eastern Long Island.

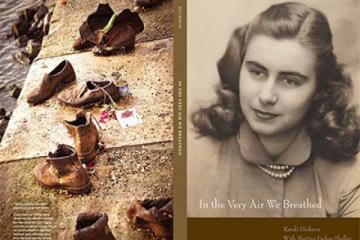

Among these couples and a few single women, I met Maritza, a beautiful and graceful woman in her 40’s, a Hungarian born Jew, who grew up in Budapest and lived there until just after WWII. For most of the nearly 45 years I have known her, she rarely spoke of her experiences during the War and I came to understand that she, like many others who suffered at the hands of the Nazis and anti-Semitism, preferred not to relive such brutal memories.

Although I was always curious to know more about her history, I wanted to respect her privacy, so rarely “pried” into her life under Nazi occupation. When I was in my late 40’s, I realized one of my dreams. I flew to Budapest to meet Maritza while she was there visiting her family. By this time, we had been close friends for over 20 years. From our shared love of tennis, Maritza and our other friends nourished my growth with access to theatre, music, film and art, so central to all of their lives. Maritza seemed so accomplished to me! She was an artist, creating beautiful stained glass and watercolors, (which we have practiced together throughout the years) and worked as an airbrush artist in a studio in New York City. But she also volunteered one day a week at the Legal Aid Society instead of taking long weekends at the beach, gave talks for UNICEF and was always learning, taking classes at the New School on everything from movies to Chinese ink brush to repairing a motorcycle. Naturally, traveling to her childhood home was an honor to me!

At the time of my visit, her 95-year-old mother was still alive, but had just moved into a senior care facility from the tiny apartment she had lived in overlooking the Danube. Maritza’s older sister Dolly still taught ballet to young children, and her husband Pista was a director in the theatre. They had a two-bedroom apartment in Budapest, where Maritza preferred to stay. I was generously offered her mom’s vacant apartment, at the Danube near the bridge to Margit Island. Each day I would meet Maritza for part of the day, and she would help me explore Budapest with its famous bridges, and the beautiful countryside surrounding the city. We swam in beautiful public “wave pools” that replicated the movement of the ocean. We traveled by train through red fields of poppies to visit the studio of Margit Kovacs, one of Maritza’s favorite sculptors. I had recently read Kati Marton’s book Wallenberg and I was excited to see many of Imre Varga’s sculptures including the statue of Raul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who established “safe houses” and saved so many lives in Budapest during the Holocaust.

I met some of her childhood friends, and we drove with one named Stephen in an old VW Bus to the hills where their summer villas had stood close to one another. Although we did not glimpse any of their actual homes, I could imagine them as children running playfully around the orchards on long summer evening. Sometimes, walking the city together, she would recount some of the history of the city and her life growing up there. Still, I did not probe too deeply, letting Maritza take the lead on what she wanted to share.

Fast forward nearly twenty years to a late spring evening in 2015 and Maritza and I are having dinner together in an outdoor café in Sag Harbor, where she has a second home. That morning I had heard a piece on NPR about the dwindling generation who are still available to give first-hand accounts of the Holocaust. Although Maritza is healthy with an amazing intact mind and memory, she is now in her late 80’s. I say, “Maritza, I don’t know why it has always been so difficult for me to ask you this, but I’m really interested in hearing your life story.” She merely laughs and the conversation turns elsewhere. But a week later I call her. “I was serious about wanting to hear and write about your life,” I say cautiously. She demurs, saying her life is not all that interesting. I assure her that at least to me, it is. And this time she says, “OK.”

Thus began a journey for both of us. We met weekly during the summer months, usually sitting under tall oak trees in her quiet backyard, and as summer waned, these interviews stretched into the winter months in various sites in New York City.

Four years have passed, as interviewing turned into researching, writing, and mutual reading of drafts. Maritza once asked, “What interests you about my life besides my experiences during the war?” “Everything!” I replied. For this is not just the story of one woman’s experiences during WWII, from when Germany invaded Hungary on March 19, 1944, and surrendered to the Allies on May 7, 1945. It is the story of a remarkable life, lived fully whether in times of great luxury or terrible deprivations, of continued accomplishments and tragic happenings. Her story has taken me deep into the history of Hungary, learning about the rich heritage that Hungarian Jews share not only in their own country, but in remarkable accomplishments that have enriched our world. I am deeply grateful for this opportunity and greatly humbled to be entrusted with her memories.

In the Very Air We Breathed

A note about the text: While much of this story draws directly from transcripts of our interviews and conversations following those, I often used research to supply context and fill in historical information that a reader might not have. All the drafts were read by and approved of by Maritza, as agreed upon when we first began this project.

In March of 1938, when I was nine years old, the Anschluss happened=Germany annexed Austria, our closest neighbor to the West. Yet we still lived as we’d lived before. Yes, my father had to have some different kind of business—but he still made money. We continued with our schooling. Life remained largely the same for us in Budapest, even as the Germans were rounding up Jews and other “undesirables” across Europe and building their concentration camps, beginning with Dachau in 1933, the year Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany.

Chapter One • Life Interrupted

Although I knew some Bible stories from my mandatory religion classes in school, I never believed in God. In fact, I don’t think I ever heard the word God spoken in my home by any members of my family. However, had I been a believer, I’m sure my faith would have been sorely tested on a tranquil, sunny Sunday, March 19, 1944.

My older sister and myself, both teenagers, were attending a Bach concert at the beautiful Saint Teresa’s Church in Budapest. We emerged from its soaring ceilings and graceful arches, filled with Bach’s stirring melodies, and our world had changed. Massive gray steel tanks, their menacing long snouts leading the way, flooded the avenues along the Danube. Soldiers of the Wehrmacht with Third Reich armbands, boasting the Nazi swastika, strutted two by two in black boots, long belted overcoats and the distinctive German steel helmet, the Stahlhelm. Trucks overflowing with German soldiers rolled beside the tanks as well as smaller open motorcars, carrying two or three German military personnel. The expansive boulevard we so loved had become cramped and tense, filled to the margins with guns and soldiers. Adolf Eichmann and other SS officers were among them, sent by Hitler to accelerate the “final solution” for Hungary’s 750,000 Jews. Nazi Germany had invaded Hungary.

Having heard the news, my parents, who were hiking in the Buda mountains just outside of the city, hurried home, and when my sister Dolly and I arrived back at our apartment, my father was already on the phone working to procure false papers for us. He tried to secure as many lifelines as possible, knowing that might be our only chance of survival. We eventually had papers from the Vatican and Sweden as well, but our first papers changed our identities to Christians. Our false papers mirrored us—father, mother, and two teenage daughters. We lost the telltale “I” for Israelite, or Jew, which appeared on all our documents, and my father’s occupation went from owning and operating a textile factory to physical education teacher, about as far from anything we could imagine for him with his slight limp.

Could we have known that our fellow Hungarians, our neighbors and our countrymen, our police and our government would cooperate with the Nazis and betray us with such enthusiasm? We thought, naively, we might be spared the fate of so many other European Jews. After all, Hungarian Jews had always been proud patriots, enjoying a symbiotic relationship with our fellow Hungarians, and making major contributions to the prosperity of our country. We trusted that Regent Horthy, an aristocrat and not—we thought—a Nazi, would protect us. There will always be debates about what Jews everywhere could have known or might have done had they known Hitler’s plans. But even as present day Hungarians attempt to whitewash their complicity—erecting in 2014 (under cover of night and with police guards) a controversial monument portraying themselves as “victims” of Nazi Germany, the truth is that most Hungarians turned their backs on us and cooperated fully with the German genocide.