Novel Appearances: French Book Art at the New York Public Library

A thin forest green box lies adrift in a sea of papers: meticulous diagrams of conical and cylindrical machine parts, a small sliver with a few words, a vortex of ninety-three sheets sprawling outward from the center. Large letters composed of small circles atop the box spell out "La Mariée mise á nu par ses celíbataires, máªme" (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even), the book's title. Yes, it's a book, even though unpacked the view resembles more the workspace of an obsessive genius. Also known as the La Boá®te verte, it's a book in the loosest sense. The pages contain replications of Marcel Duchamp's elaborate notes used to plan and build his "final" masterpiece, The Large Glass, which depicts a "love machine" that, because it will never work, forever frustrates its would-be machine bride and groom. There's no set order for the sheets, and so anyone who attempts to follow Duchamp's logic will also remain perplexed.

Duchamp's Boá®te verte is one among many livres d'artistes on view at the New York Public Library's exhibition, "French Book Art | Livres d'Artistes: Artists and Poets in Dialogue," which features over a century's worth of collaborations between artists and writers, and sometimes, like Duchamp, with the same person performing both roles. The one hundred and twenty six books on display contain love poems, pen drawings, erotic stories, and abstract woodcuts by French visionaries from the Belle Epoque onward, although the output from the second half of the century is thinner, and dimmer, in comparison. Whether French by birth or by virtue of residence, when gathered under one roof, the talent is staggering—from Manet, Mallarmé, Apollinaire, and Picasso to Dubuffet, Bataille, and Beckett—and the works are as varied as the artists. They range from the chaos of Duchamp's Boá®te verte to the simplicity of Picasso's red strokes that underscore Reverdy's Les chant des morts, and come as compact as the pocket-sized Cette Surface by André du Bouchet and Pierre Tal-Coat.

The French livre d'artiste has roots in medieval times, when devotional books were often illustrated, like the popular bestiary, which depicted animals with human traits, and vice versa. Tales of romantic love and chivalry went hand in hand with artwork in the 17th and 18th centuries, but it wasn't until the 1829 French translation of Goethe's Faust, which included ominous lithographs by Delacroix, that art and literature were brought together in a volume that clearly resembled the livre d'artiste in its modern incarnation.

Close to fifty years later, Stéphane Mallarmé and Edouard Manet, old friends who admired one another's work, joined forces, with Manet providing illustrations for Mallarmé's poem, L'Apres-midi de un faun. This cross-pollination resulted in the birth of the contemporary livre d'artiste. Mallarmé once said, "the world is made to culminate in a fine book," and he set out as if to achieve this distinction by overseeing the entire production, down to the pink and black tassel bookmarks that match the colors of Manet's prints. Manet's illustrations are delicate and playful, and his faun's face bears resemblance to Mallarmé's.

Many of the books that followed were borne of friendships between artists and poets. In Paris at the time there was a great intermingling among artists, writers, and musicians; ideas flowed between friends and cross-genre collaborations blossomed. Picasso provided some of his first Cubist illustrations for his friend Max Jacob's novel Saint Matorel, and a few years later he became Jacob's godfather when he was baptized Catholic. Apollinaire, whose poetry is included in three volumes in the exhibit wrote a definitive book on Cubism. Duchamp, in turn, mocked Apollinaire with his Apoliná¨re Enameled, his answer to Apollinaire's statement that the modern style was not to be found "in the facades of houses or in furnishings as in iron constructions—machines, automobiles, bicycles, and airplanes." It is a paint advertisement transformed into art, with the words "Sapolin enamel" painted over—so that no one could mistake his intentions—to read, APOLINÈRE ENAMEL.

It's as though a bomb were inadvertently dropped on the essence of book art during the first World War; it emerged on the other side fundamentally changed, spinning off in many directions. Dada shook up the established ideas of art and literature, especially in Paris where the movement was well-grounded in the written word, with poets like André Breton, Tristan Tzara, and Paul ူluard at the helm. The new methods of making art and creating poetry mirrored each other: Tzara would cut up newspaper articles, and Arp drawings, and each would let the pieces fall to create a poem, or a picture, from the chance arrangement.

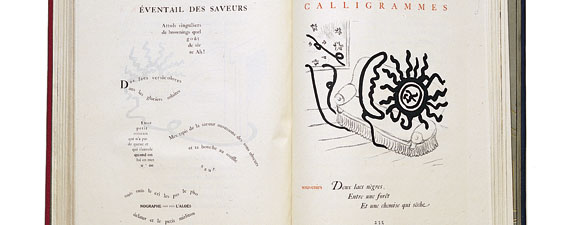

During the war Apollinaire invented a new form of poetry, the calligram, which evokes images with the stanza's lines. On the displayed pages of his book Calligrammes, the lines of poetry create a face: an eyelash, an eyelid, the contours of lips. Giorgio de Chirico's paired drawing is fantastical and playful though oddly matched (the fact that this volume debuted in 1930, twelve years after Apollinaire's death, might play a role in the incongruity). A sun and a moon sit on a sofa, each tethered to the starry sky by a long, winding umbilical cord. And then Picabia takes the calligram one step further with his "Poá¨me Plastique": the meandering lines of poetry form a shape similar to an Arp woodcut.

(The extensive display of Dadist books here, which includes contributions by Tzara, ူluard, Max Ernst, Hans Arp, and Marcel Janco, coincidentally complements the current Dada exhibition at MoMA, which features not only a wide array of books, but also numerous Dada journals filled with art and poetry. Apoliná¨re Enameled is on view, too, but don't bother searching for Duchamp's Large Glass as I did—although it's in the exhibition catalog, MoMA has chosen not to include it in the New York show.)

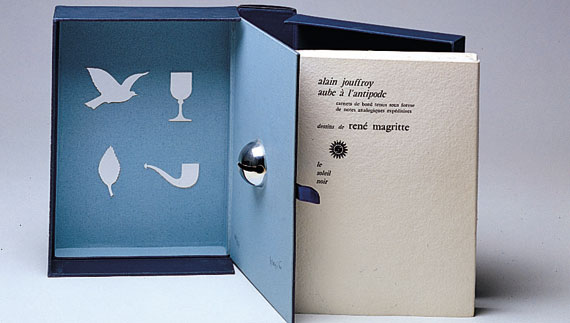

No collection of books is truly complete without a hefty dose of eroticism, which was doled out in the livres d'artistes of the 1930s and '40s. Georges Batailles, who had already written his classic Story of the Eye, supplies an equally lewd story in Madame Edwarda, which involves an encounter in a mirror-walled brothel, a fainting episode, and a threesome in a taxi. In this edition Jean Fautrier scrawled crude outlines of naked men and women having sex between the passages of text. Fautrier infuses more sensuality in his subsequent work, La Femme de ma vie, a purple-ink etching of a reclining woman's labia, mounted fittingly on a piece of pink lingerie lace.  Despite the inventiveness and contemporary trappings of the books from the second half of the century, the most notable were produced over thirty years ago, and often by artists and poets who were holdovers from the previous decades. Tzara and Picasso's La Rose et le chien, published in 1958, features a poem written in concentric circles that rotate to create an endless variation of poems within the one. And although it dates from 1966, the simple blue casing designed by René Magritte for Alain Jouffroy's Aube a l'antipode looks as though it could have been published this year. A bird, a glass, a leaf, and a pipe are cut from the front cover, forming a square, and the top half of a sleigh bell sits perfectly centered on its divider. The seeming elision of forty years can be explained, in part, by the echoes found today in the imaginative designs of McSweeney's books and journals. The cover for Stephen Dixon's I., published in 2002, is curiously reminiscent of Magritte's: the title has been die-cut from the cover, exposing Daniel Clowes' portrait of the author peering through from the page below.

Despite the inventiveness and contemporary trappings of the books from the second half of the century, the most notable were produced over thirty years ago, and often by artists and poets who were holdovers from the previous decades. Tzara and Picasso's La Rose et le chien, published in 1958, features a poem written in concentric circles that rotate to create an endless variation of poems within the one. And although it dates from 1966, the simple blue casing designed by René Magritte for Alain Jouffroy's Aube a l'antipode looks as though it could have been published this year. A bird, a glass, a leaf, and a pipe are cut from the front cover, forming a square, and the top half of a sleigh bell sits perfectly centered on its divider. The seeming elision of forty years can be explained, in part, by the echoes found today in the imaginative designs of McSweeney's books and journals. The cover for Stephen Dixon's I., published in 2002, is curiously reminiscent of Magritte's: the title has been die-cut from the cover, exposing Daniel Clowes' portrait of the author peering through from the page below.

Perhaps McSweeney's will provide a lifeline to revitalize book art, or at least keep filching ideas from its past. In fact, the most recent issue of McSweeney's Quarterly Concern is an art book in its own right: contemporary artwork is interspersed among the volume's fiction, and on the cover a painting of layered fields and creeping tendrils has overtaken the editor's note and issue credits beneath. McSweeney's is like the émigré grandchild of the livre d'artiste: it's not to be mistaken for the same entity, but it's alive and thriving while the spirit of the traditional livre d'artiste has withered. While McSweeney's has yet to forge a novel form of book art, its reinventions never bore. The penultimate issue featured an assortment of loose letters, pamphlets, cards, and stories, enclosed in a cigar box. Echoes again, this time of Duchamp.

Photo credits for the livre d'artiste images:

Duchamp:

Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). La Mariée mise á nu par ses célibataires, máªme

[The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even] (also called La Boá®te

verte [The Green Box]). Paris: Editions Rrose Sélavy, 1934. NYPL, Rare Book

Division. © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris /

Succession Marcel Duchamp. Photograph © Michel Nguyen

De Chirico:

Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918) | Giorgio De Chirico (1888–1978).

Calligrammes [Calligrams]. Paris: Gallimard, 1930. NYPL, Spencer

Collection. © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome.

Photograph © Michel Nguyen

Magritte:

Alain Jouffroy (b. 1928) | René Magritte (1898–1967). Aube á l’antipode

[Dawn on the Other Side of the World]. Paris: Le Seuil noir, 1966.

Bibliothá¨que littéraire Jacques Doucet. © 2006 C. Herscovici, Brussels /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph © Michel Nguyen

A thin forest green box lies adrift in a sea of papers: meticulous diagrams of conical and cylindrical machine parts, a small sliver with a few words, a vortex of ninety-three sheets sprawling outward from the center. Large letters composed of small circles atop the box spell out "La Mariée mise á nu par ses celíbataires, máªme" (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even), the book's title. Yes, it's a book, even though unpacked the view resembles more the workspace of an obsessive genius. Also known as the La Boá®te verte, it's a book in the loosest sense. The pages contain replications of Marcel Duchamp's elaborate notes used to plan and build his "final" masterpiece, The Large Glass, which depicts a "love machine" that, because it will never work, forever frustrates its would-be machine bride and groom. There's no set order for the sheets, and so anyone who attempts to follow Duchamp's logic will also remain perplexed.

A thin forest green box lies adrift in a sea of papers: meticulous diagrams of conical and cylindrical machine parts, a small sliver with a few words, a vortex of ninety-three sheets sprawling outward from the center. Large letters composed of small circles atop the box spell out "La Mariée mise á nu par ses celíbataires, máªme" (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even), the book's title. Yes, it's a book, even though unpacked the view resembles more the workspace of an obsessive genius. Also known as the La Boá®te verte, it's a book in the loosest sense. The pages contain replications of Marcel Duchamp's elaborate notes used to plan and build his "final" masterpiece, The Large Glass, which depicts a "love machine" that, because it will never work, forever frustrates its would-be machine bride and groom. There's no set order for the sheets, and so anyone who attempts to follow Duchamp's logic will also remain perplexed.