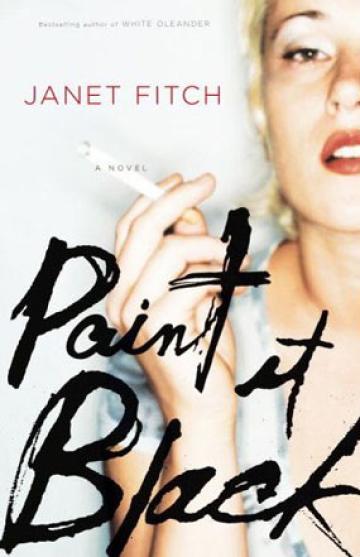

Janet Fitch's PAINT IT BLACK

Little, Brown, September 2006, 352 pages, $24.99

Janet Fitch's novels make fine companions for the beach, the subway, the doctor's office waiting room. Page-turners, they flow with a fairly straightforward progression of minor conflicts and resolutions that can be interrupted and restarted with ease. Vivid depictions of landscape, like a backyard mint patch planted in old tires, and characters with distinctive traits ("Her eyes flashed green fire. His own were a cloudy sea.") anchor the scenes in physical detail. But when you come up for air, you wonder how you so quickly covered so much terrain; fifty pages flew by without pause. It leaves you craving something else, something more.

In Fitch's first novel, White Oleander, an Oprah Book Club pick, Astrid is shuffled from one foster family to another after her mother, a narcissistic poet, murders her former lover with the extract of the poisonous oleander plant. She encounters a sequence of dilemmas, and yet the story resolves with the narrative threads tied into a little bow. Paint It Black, Fitch's second novel, deviates in subject but not in effect: in the heart of the '80s LA punk scene, striking twenty-year-old art model and aspiring actress Josie Tyrell finds meaning through her lover Michael Faraday, son of professional pianist Meredith Loewy and famed writer Calvin Faraday.

Paint It Black opens with Michael's suicide. Josie and Meredith are left to pick up the pieces, each resentful of the other, and each wishing to claim Michael's loss as exclusively their own. Josie's grief is palpable, and understandable; she's a lost soul who defined herself through her relationship with Michael, and once again is set adrift. But Fitch falls into the trap of forming Josie's character almost entirely in relation to Michael. Most passages of Josie's self-reflection strike a similar cadence: "Michael thought she was better than that, thought she was special. He couldn't see how ordinary she was. It was just when she was around him, she was smarter, original. He was like those magnets that changed the shape of the filings, made them stand up like hair." At points Josie seems less a character than a cipher through which scenes from her past with Michael are projected.

The florid prose hits heightened pitches but never attempts to reach beyond the immediate action, leaving the peaks and valleys of Josie's inner turmoil as enticing as watching a cat chasing its tail. Josie's whims often dictate the drama that follows, whether she's certain that Meredith hired a hit man to kill her, or later, when viewing pictures of an adolescent Michael with his mother, she becomes convinced that their relationship turned incestuous one summer in St. Tropez. And, despite the vitriol and bitterness slung between Josie and Meredith throughout, Josie eventually retreats to Meredith's house, with Meredith welcoming her as a daughter-in-law. It all comes together a little too conveniently.

Too often Fitch's tendency towards melodrama preempts any deeper ruminations with a new plot twist, an obstacle to surmount, or a climactic argument that will (as often as not) reverse itself in another hundred pages. Grudges are as pliable as silly putty; the back-and-forths and twist-and-turns cancel themselves out. And yet, Fitch seems content to distract the reader with the hypnotic cadence of her prose and the sensationalistic storylines, obscuring the vacancy beneath.

Janet Fitch was born in Los Angeles, a third-generation native, and grew up in a family of voracious readers. As an undergraduate at Reed College, Fitch had decided to become an historian, attracted to its powerful narratives, the scope of events, the colossal personalities, and the potency and breadth of its themes. But when she won a student exchange to Keele University in England, where her passion for Russian history led her, she awoke in the middle of the night on her twenty-first birthday with the revelation she wanted to write fiction.

Janet Fitch was born in Los Angeles, a third-generation native, and grew up in a family of voracious readers. As an undergraduate at Reed College, Fitch had decided to become an historian, attracted to its powerful narratives, the scope of events, the colossal personalities, and the potency and breadth of its themes. But when she won a student exchange to Keele University in England, where her passion for Russian history led her, she awoke in the middle of the night on her twenty-first birthday with the revelation she wanted to write fiction.